The Townshend Acts

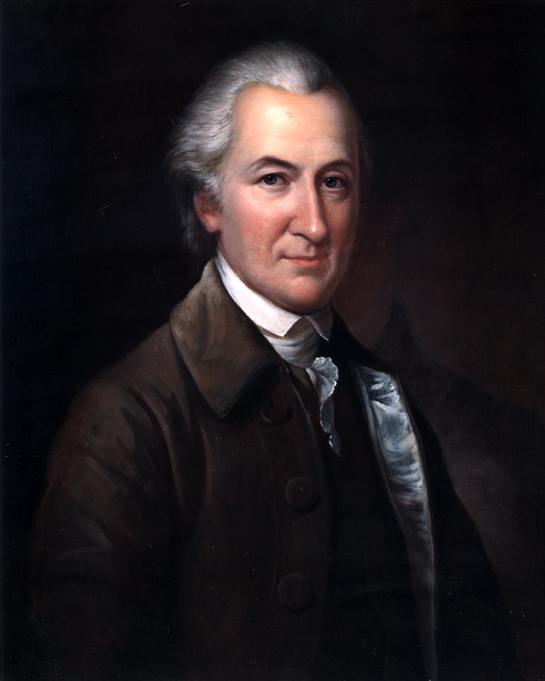

Charles Townshend

Charles TownshendThe Townshend Acts were a series of five acts passed under the leadership of Charles Townshend, the chancellor of the Exchequer, meant to raise revenue and consolidate Parliament's power over Britain's colonies in America.

When the Acts were passed, nearly a year after the Stamp Act was repealed, they resurrected hostilities toward Britain in America and renewed the colonists' rioting and boycotts of British goods.

The Townshend Acts added new taxes to common items, but even more importantly, set up a new system of Customs Commissioners and Vice-Admiralty courts for enforcement of the new taxes. Revenue from the taxes was to be used for the salaries of Royal Governors and judges to keep them dependent on Parliament, rather than the local assemblies.

This attempt to increase Parliament's power over the colonies alarmed the colonists, leading to outbreaks of violence and eventually the occupation of Boston. You can learn more about the Townshend Acts below.

Background to the Townshend Acts

Prime Minister William Pitt

Prime Minister William PittShortly after the Stamp Act was repealed, William Pitt, the 1st Earl of Chatham, succeeded the Marquess of Rockingham as Prime Minister of England. Pitt was considered to be a strong advocate of the colonies and had fought vigorously for the repeal of the Stamp Act in Parliament, where he was a member at the time. Pitt's speech, In Defense of the Colonies, in which he agreed that Parliament had no right to tax the colonies, made him a hero to the colonists.

Pitt's ascendency to Prime Minister should have opened up a new season of good relations between Parliament and its British colonies because he was so celebrated by the colonists, but the opposite happened. Pitt was very sick and is now thought to have suffered from severe depression. He was often incapacitated and gone from Parliament.

Consequently, Charles Townshend, the chancellor of the Exchequer, became the de facto leader in Pitt's absence. The Chancellor of the Exchequer oversees Britain's treasury, controlling the government budget, economic policy and taxation. Townshend was much less friendly to the colonists and he began to push measures through Parliament in an effort to tighten Britain's control over the rebellious colonies.

At the time of Townshend's ascendency, British citizens were complaining of high taxes, much of which were going to service the huge debt accrued during the French and Indian War, called the Seven Years War in England. Lord Rockingham, the previous Prime Minister, had been forced to raise taxes on subjects in England to help cover the revenue lost from the repealed Stamp Act. Rioting for bread began breaking out across England.

Lord Townshend proposed that an unpopular tax called the "land tax" be reduced from four shillings to three, but not until the following year. Influential citizens took Townshend's suggestion and lobbied their members in Parliament for an immediate reduction to three shillings. This measure passed and reduced the anticipated revenue for 1767 by £500,000 pounds. This forced Townshend to find somewhere else to raise additional revenue.

Townshend's planTownshend came up with a scheme to raise revenue by taxing imported items into the British American colonies. The plan was estimated to raise only £40,000 pounds, a fact which others members of Parliament complained about. Townshend, though, knew the Americans would be reluctant to pay additional taxes. So he promoted the idea that they would place a small tax on them at first and then once the Americans were used to it, they could raise the amount to cover the shortfall in the Treasury.

At first, Townshend promoted the new taxes as a way to cover the shortfall from the reduced land tax. Later, he said it could also be used to defray expenses of keeping the British forces in the colonies.

Later Townshend announced that the new import revenues would also be be used to pay the salaries of royal governors and judges in the colonies who were previously paid by the colonial assemblies. This was partly necessary because the colonial assemblies were sometimes refusing to pay officials who did not comply with their demands. The affect of this new scheme would be to make these governors and judges dependent on the Crown for their livelihood and, therefore, more pliable and favorable to Parliament's wishes.

It became apparent that the new taxes and laws were Townshend's attempt to solve several problems with one set of laws, one of the chief problems being the need to regain control of the colonies.

Colonial Boston

Colonial BostonIn addition to the new taxes, a new regime of customs commissioners would be created in the colonies to enforce them, also to be paid for with revenue from the new taxes. The customs commissioners would be equipped with writs of assistance, legal warrants that gave them authority to search private property for smuggled goods.

The plan also called for the vice-admiralty court to be expanded from one court, in Halifax, to four, with additional courts in Boston, Philadelphia and Charleston. These courts would try violators of the new import taxes.

Finally, measures would be passed to deal with New York's refusal to comply with the Quartering Act of 1765, which required the colony to provide and pay for food, housing and supplies for British soldiers in the colonies.

All of these measures were passed in a series of acts that came to be known as the "Townshend Acts," since they were championed by Lord Townshend. Four of the Acts were passed between June 15 and July 2, 1767 and the last in June 1768. They are: the New York Restraining Act, the Revenue Act of 1767, the Commissioners of Customs Act, the Indemnity Act of 1767 and the Vice-Admiralty Court Act.

The Five Townshend Acts

Quartering Troops

Quartering TroopsThe New York Restraining Act

The New York Restraining Act was the first of the Townshend Acts to be passed. Parliament had passed the Quartering Act of 1765 in June of that year. The Act called for each colony to provide and pay for food, housing and supplies for any British troops staying within that particular colony.

Most of the colonies had relatively few troops in them. Any troops on the western front were not included and were paid for out of the British treasury. New York, though, had a disproportionately large number of troops compared to the other colonies. Part of this was due to the fact that New York had the largest and busiest port through which many of the arriving and departing British troops had to pass. This caused a disproportionate number of troops to always be stationed in New York City. In addition, the British kept a large contingent of soldiers at Albany.

The New York Provincial Assembly viewed the demands of the Quartering Act as an unconstitutional tax since they had no representatives in Parliament to advocate for themselves. At first, they agreed only to provide firewood and candles. Later, when a huge contingent of 1,500 soldiers arrived in New York, the Assembly refused to pay anything for them.

This angered Townshend and the rest of Parliament who then passed the New York Restraining Act, also called the Suspension Act or the Restraining Act, on June 15, 1767. The Act forbade the Assembly and the Governor from passing any laws, resolutions or votes of any kind until they fulfilled the obligations required of them by the Quartering Act. It also made "null and void" any acts or resolutions they passed refuting the demands of the Restraining Act.

The demands of the New York Restraining Act were never implemented, however, because by the time Parliament passed the Act, the Assembly had reluctantly changed its mind and began to pay some, though not all, of the expenses required in the Quartering Act. They clearly had a change of mind because they anticipated punishment from Parliament for non-compliance.

You can read the text of the New York Restraining Act here.

The Revenue Act of 1767The Revenue Act of 1767 was the core of the Townshend Acts. It called for a new tax on glass, lead, painters colors, tea and paper. These were all items the colonists were only allowed to buy directly from Britain, in order to benefit British merchants and keep the money within the Empire, rather than giving it to foreign competitors. There were also new regulations concerning the import of coffee and cocoa and the procedures for going through customs.

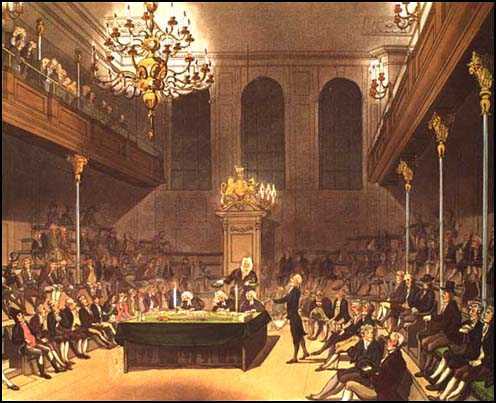

British Parliament

British ParliamentIn addition to the taxes, the Revenue Act of 1767 empowered customs commissioners with "writs of assistance." Writs of assistance were search warrants that could be used to enter private property such as warehouses, cellars, ships or private homes to search for contraband material.

Smuggling of foreign goods, which were often cheaper than British goods, was common in the colonies. If foreign goods were smuggled in, the colonists would not buy British goods and the tax revenue would drop. If British goods were smuggled in and did not pass through the customs office in each port, the taxes could be avoided as well. Writs of assistance gave broad authority to officials to search for and confiscate smuggled items and to prosecute the smugglers.

The use of writs of assistance had already been a point of strong contention between the colonists and Parliament in the past. The same writs were in use during the passage of the Sugar Act and the Stamp Act and had been used off and on throughout colonial history. During the Stamp Act crisis in particular, the colonists had vehemently protested that their use was a violation of their right to be secure in their own homes and private property.

English law had long established that private property was out of reach of the government without a properly executed search warrant by a judge. Writs of assistance, as used in trade matters, gave blanket permission to officials to search for smuggled goods on private property. They removed any requirement for concrete evidence that would arouse suspicion that a violation had occurred and did not require that a judge review the evidence and decide whether or not the evidence justified issuing a warrant.

Officers at the Door

Officers at the DoorToday, people understand that the colonists were angry with England because of unjust taxation, but often fail to understand the importance which this issue held for the colonists as well. In fact, it was so important that it made it into the Constitution as a protected right in the Fourth Amendment, which guarantees people to be secure in their "persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures" and requires that "no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized."

The Fourth Amendment requires that there must be "probable cause" to issue a search warrant. In other words, there must be some concrete reason why the authorities believe the law has been violated. It also directs that the specific place and the items to be seized must be described in detail in the warrant. This greatly reduces the power of the government to search any place it wants to, whenever it wants to and from seizing anything it finds.

Instead, it must all be laid out in the warrant and the authorities must strictly obey the written law. In the colonial time period, however, writs of assistance granted broad authority for officials to search anytime, anywhere.

Read the text of the Revenue Act of 1767 here.

The Commissioners of Customs ActThe Commissioners of Customs Act was passed along with the Revenue Act of 1767 on June 29, 1767. The Commissioners of Customs Act created a new board of Commissioners in the colonies to oversee the collection of all import taxes and to prosecute those who violated the taxes or regulations in any way.

The Custom House in Boston can be clearly seen on King Street in the Boston Massacre engraving by Paul Revere

The Custom House in Boston can be clearly seen on King Street in the Boston Massacre engraving by Paul RevereBefore this Act, the enforcement of trade in the Americas was handled by the Customs Commission back in England. Due to the great distance, enforcement was spotty. Any time an issue arose, the parties involved would have to wait for messages to be sent both ways across the ocean. Customs officials in America were often bribed to look the other way. Importers could save more money by paying a bribed official who would charge them less than the law required or just let them through without paying any taxes at all. It was extremely inefficient and lots of tax revenue fell through the cracks.

The new customs commissioners were to be headquartered in Boston where the strongest opposition to taxation was centered. Five commissioners were appointed to the Board there and numerous other officials were soon appointed for other ports.

It is these officials who used the writs of assistance authorized in the Revenue Act to conduct searches on private property and seizures of smuggled goods. These raids on private property caused an enormous amount of strife and were one of the primary reasons for the colonists' rebellion.

In April and May of 1768, two ships owned by John Hancock were involved in incidents that led to a mob attacking customs officials who fled the city.

The newly appointed Customs Commissioners were the targets of violence and protests across the colonies. Violent incidents occurred throughout the colonies, especially in Rhode Island and Massachusetts to stop them from collecting taxes and enforcing trade regulations. Smuggling was rampant. Some scholars view the creation of the Customs Board in the colonies and their efforts to catch smugglers as one of the primary triggers of the American Revolution.

You can read the Commissioners of Customs Act here.

The Indemnity Act of 1767The fourth of the Townshend Acts, passed along with the Revenue Act of 1767 and the Commissioners of Customs Act, was the Indemnity Act of 1767. The Indemnity Act of 1767 eliminated all taxes on tea imported into Great Britain by the British East India Company. The British East India Company was one of Britain's largest companies and was near bankruptcy due to high taxes and much cheaper Dutch tea that was being smuggled into the Empire. By eliminating the tax to import tea into Britain by the British East India Company, tea which was then exported to the colonies could be sold there at a rate even lower than the smuggled Dutch tea.

East India Company Coat of Arms

East India Company Coat of ArmsThe American colonies were one of the largest markets for tea from the British East India Company. They consumed more than a million pounds a year at that time and every time smuggled Dutch tea was consumed instead of British tea, it dented the company's profits and sucked tax revenue out of the treasury.

The new lower priced tea would cause the colonists to buy more British tea, on which they would be paying the new tax enacted in the Revenue Act. This would shift the burden of this tax completely from British taxpayers to the colonies. It would help the ailing British East India Company and would fill the Treasury with much needed tax revenue, or so Parliament's reason went.

The Indemnity Act of 1767 required the British East India Company to make up the difference if tax revenue was less than it was before the tax was removed. It was assumed that the increased sales of tea would make this unnecessary though. The Act also required that tea be resold to the Americas in the same "chest, cask, tub, or package" in which it was imported to Great Britain. This requirement was expected to increase tea sales because the tea would not be broken down into smaller portions.

Further, the Indemnity Act forbade any smuggled tea confiscated in England from being resold in England. Instead, it had to be resold to the colonies or to Ireland. This was done to prevent the sale of smuggled tea from undercutting the British East India Company's price. The Act also awarded the defendant three times the alleged damages if he was falsely accused of violating the Act.

You can read the text of the Indemnity Act of 1767 here.

The Vice-Admiralty Court ActThe Vice-Admiralty Court Act was not passed until the following year on July 6, 1768. It is usually considered one of the Townshend Acts, even though Townshend was already dead by this point. Lord Townshend died suddenly on September 4, 1767 only a few months after the first set of Townshend Acts was passed.

After Townshend's death, the Lords Commissioners of His Majesty's Treasury, the officials over the treasury, recommended to the King that the sole Vice-Admiralty Court in Nova Scotia be augmented with three more such courts in Boston, Philadelphia and Charleston. As such, this was not an Act passed by Parliament, but an Act passed by the Commissioners of the Treasury with the King's approval.

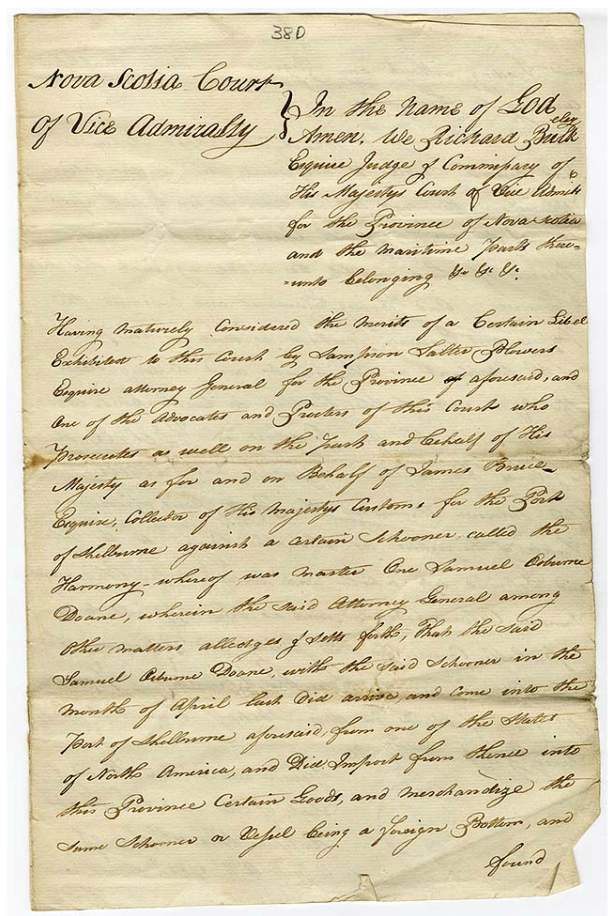

Record of the decree of Richard Bulkeley, Registrar of the Vice-Admiralty Court at Halifax, Nova Scotia, awarding the schooner Harmony to the claimant, Samuel Osborne Doane

Record of the decree of Richard Bulkeley, Registrar of the Vice-Admiralty Court at Halifax, Nova Scotia, awarding the schooner Harmony to the claimant, Samuel Osborne DoanePrior to the French and Indian War, all of Britain's colonies in the America's were served by twelve vice-admiralty courts in twelve different regions. Admiralty courts existed to officiate in maritime disputes, often deciding matters of conflict between sailors and merchant ship owners or in contractual disputes between manufacturers or exporters and ship owners. These courts were local courts and their judges were chosen from the local population. They were also paid for by the local colonial assembly and as such, were not considered to be beholden to the government back in Britain.

Vice-admiralty courts operated differently than regular courts. They did not use juries to decide cases. Instead, the judge heard all the evidence and made the decision. Until the French and Indian War, these courts handled only maritime disputes. During the War however, their jurisdiction was increased to handle the disposal of enemy ships caught during the war.

In addition, judges of the admiralty were awarded a 5% commission of the value of the smuggled goods and seized ships if they gave a guilty verdict. This reward system made it difficult to get a fair trial.

When accused smugglers were tried in the local vice-admiralty courts, the local juries, who believed the customs taxes were illegal and were often guilty of violating the laws themselves, would often judge a defendant innocent, not wanting to convict his fellow citizen, even if he was clearly guilty. This led Parliament to create a new court in Halifax, Nova Scotia in January 1763 to handle cases in which it was believed the local courts and juries would not give a verdict favorable to the government.

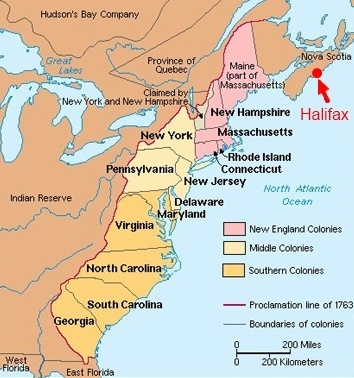

13 colonies map showing Halifax, Nova Scotia

13 colonies map showing Halifax, Nova ScotiaRoyal prosecutors would decide whether to bring charges against an accused smuggler in the local courts or in the Vice-Admiralty Court in Nova Scotia based on whether or not they believed a guilty verdict could be obtained in the local court. If it was doubtful that a local jury would bring a guilty verdict, the trial was shipped to Nova Scotia. The expenses of getting to Nova Scotia fell to the accused and failure to appear meant an automatic guilty verdict. The Court operated by the principle of guilty until proven innocent.

The Halifax Vice-Admiralty Court had authority over cases from Newfoundland to the Floridas and was staffed by and paid for by the British government. Consequently, its decisions were often favorable to Parliament's wishes. The Sugar Act of 1764 increased the jurisdiction of this Court to handle the enforcement of customs regulations and cases of smuggling.

The Townshend Acts increased the responsibilities of this Vice-Admiralty Court to prosecute all matters dealing with customs, trade and smuggling. Since Nova Scotia was so far away from most of the lower colonies and since the Commissioners of Customs Act would likely increase the number of customs related prosecutions, it was deemed necessary to increase the number of the courts.

The Court at Halifax would remain, but the Vice-Admiralty Court Act added additional courts in Boston, Philadelphia and Charleston for their respective regions.

You can read the text of the Vice-Admiralty Court Act here.

Reactions to the Townshend Acts

After the Stamp Act was repealed in March, 1766, the colonists were satisfied and a period of calm ensued. Had the British Parliament left things as they were and never enacted the Townshend Acts, it is possible that the American Revolution would never have happened.

Instead, Parliament insisted once again in trying to enact taxes the colonists thought were unjust, in trying them without the use of local juries and in restraining their locally elected assemblies. This resurrected the rioting and protesting once again. The violence was not as severe as it was against the Stamp Act, but it was consistent and forceful enough to start a chain-reaction of events that ultimately caused the war.

New York eventually capitulated and paid for the soldiers room and board as required by the Quartering Act of 1765, but Parliament's attempt to restrain their activities with the New York Restraining Act alarmed the colonists. The precedent of Parliament shutting down or even disbanding the colonial assemblies would become commonplace in the years to come as the insurrection increased. This grievance would make it into the Declaration of Independence as one of King George's crimes against them.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas JeffersonThe erection of new customs offices and courts would also make it into the Declaration. Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration that "He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance." He also included the fact that various officials in the colonies were now paid for by Parliament instead of by the colonies as a grievance.

The colonists viewed trial by jury as a fundamental right of British citizens and the idea that they were to be tried without one was criminal. British history also guaranteed that people should be tried by a local jury, in the district where the crime was committed. The Townshend Acts and other acts allowed for the trials to be sent overseas and even back to England!

The use of writs of assistance, as mentioned earlier, was also considered by the colonists as a violation of their right to be secure in their private property.

Finally came the matter of the taxes, all taxes that were meant to generate revenue for the British treasury were considered illegal by the colonists since they had no representation in Parliament.

Townshend knew the colonists would not like the new taxes, he did not however, believe that they would rebel against them, because they had already made a distinction between internal and external taxes during their rioting against the Stamp Act.

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin FranklinBen Franklin had described in his Examination by Parliament, that the colonists called taxes "internal" if they were on daily activities that took place solely within the colonies. Taxes such as these were unconstitutional if levied by Parliament because the colonists had no representation in Parliament and it was a long standing principle of British law that taxation without consent of the population was illegal.

External taxes were those taxes placed on the import and export of goods. They fell upon activities that occurred partially outside the colonies and had to do with regulation of trade. The colonists believed it was proper for Parliament to regulate trade within the Empire in a way that would produce the most benefit for the Empire. The use of taxes on certain goods provided this benefit by preventing foreign merchants from undercutting the prices of British merchants.

Townshend himself, as well as many other members of Parliament, did not even see any distinction between "external" and "internal" taxes and viewed any such distinction as nonsense. The colonists had made clear during the Stamp Act protests, that internal taxes were illegal, but they had no objection to external taxes. Consequently, Lord Townshend believed that his taxes on imports would be acceptable to them. Lord Townshend made a serious mistake, however, because he did not properly understand the colonists' reasoning about taxes.

The Loss of the Romney Man of War by Richard Corbould Depicts the HMS Romney running aground and breaking apart off the coast of Holland in 1805

The Loss of the Romney Man of War by Richard Corbould Depicts the HMS Romney running aground and breaking apart off the coast of Holland in 1805Townshend believed the colonists defined "external taxes" as taxes on imports. The colonists, though, had a slightly more complex belief about external taxes. They believed that external taxes for the purpose of trade regulation were constitutional, but they also believed that it was illegal for Parliament to tax them by any method, solely for the purpose of raising revenue. Why would this be illegal? The same old reason... they had no representation in Parliament. Taxation should only be done by their local assemblies, in which they were represented.

What was their response? Many colonists stopped buying British goods and made their own or did without. Some started new industries to supply goods that were previously bought from England. In Boston and other places, customs commissioners were harassed and persecuted.

The new Customs Commissioners were seated in Boston and consequently, Boston took the severest brunt of their enforcement. Anticipating trouble, the commissioners requested military assistance, which was answered with the arrival of the HMS Romney, a sixty gun British warship, in May, 1768. Riots, protests and acts of violence erupted up and down the seaboard.

John Dickinson

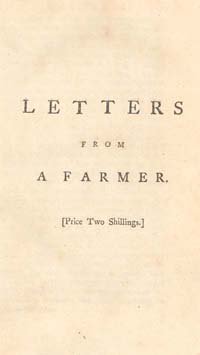

John DickinsonLetters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania

Some prominent colonists began writing campaigns to explain why the various provisions of the Townshend Acts were wrong. John Dickinson, a Philadelphia lawyer who had been a delegate to the Stamp Act Congress, began to write a series of published letters to explain why what Parliament was doing was an abuse of their its power. He would eventually write twelve letters and they became one of the most influential set of writings during the period. Some scholars consider them to be the most important written work of the American Revolution or at least second to Thomas Paine's Common Sense. They became known as the Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania because that is how Dickinson signed them.

Several years later Dickinson would serve in the Continental Congress and in the Pennsylvania and Delaware militias. He also served as President of Delaware and President of Pennsylvania for a time. While in Congress, Dickinson would be part of writing several important documents, including a Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, written with Thomas Jefferson, the Olive Branch Petition, which was Congress' final attempt to reason with King George and the first draft of the Articles of Confederation, the United States' first governing document, but he would refuse to sign the Declaration of Independence.

Two passages from Dickinson's first letter show the gist of his arguments. In it, he challenges Parliament's ability to tax through the Quartering Act and Parliament's act of restraining the New York Assembly. Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (price 2 shillings)

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (price 2 shillings)"IF the British Parliament has a legal authority to issue an order that we shall furnish a single article for the troops here, and to compel obedience to that order, they have the same right to issue an order for us to supply those troops with arms, clothes, and every necessary, and to compel obedience to that order also; in short, to lay any burdens they please upon us. What is this but taxing us at a certain sum and leaving us only the manner of raising it? How is this mode more tolerable than the Stamp Act?... AN act of Parliament commanding us to do a certain thing, if it has any validity, is a tax upon us for the expense that accrues in complying with it..." "In fact, if the people of New York cannot be legally taxed but by their own representatives, they cannot be legally deprived of the privilege of legislation, only for insisting on that exclusive privilege of taxation. If they may be legally deprived in such a case of the privilege of legislation, why may they not, with equal reason, be deprived of every other privilege? Or why may not every colony be treated in the same manner, when any of them shall dare to deny their assent to any impositions that shall be directed? Or what signifies the repeal of the Stamp Act if these colonies are to lose their other privileges by not tamely surrendering that of taxation?"

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania urged the colonists to recognize that their rights were being trampled on, but they encouraged reconciliation through negotiation, protests and economic boycotts, rather than violence.

Dickinson did realize, however, that Parliament had a history of abuse that had only been ended by violent opposition in the past. In his third letter, he addressed this:

"If at length it becomes undoubted that an inveterate resolution is

formed to annihilate the liberties of the governed, the English history

affords frequent examples of resistance by force. What particular

circumstances will in any future case justify such resistance can never

be ascertained till they happen. Perhaps it may be allowable to say

generally, that it never can be justifiable until the people are fully

convinced that any further submission will be destructive to their

happiness."

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania was published in almost every newspaper in America, making them one of the most widely read political commentaries of the era. Soon they were published together in a complete volume and were also read in England where Ben Franklin had them reprinted.

James Otis

James OtisThe Massachusetts Circular Letter

The first of John Dickinson's letters was published in December 1767. These letters helped unify and provoke the colonists to action against the Townshend Acts. Dickinson sent James Otis of Boston a complete copy of the Letters from a Farmer and told him he was expecting Massachusetts to take the lead in resisting the Townshend Acts.

Otis proposed in a Boston town meeting that the legislature write a letter stating its objections to the Townshend Acts and send it to the other colonies, encouraging them to take certain steps to resist the Acts. In February of 1768, the legislature met and approved two letters, one to the King, expressing their grievances and another which was sent to the other colonies. Samuel Adams drafted this letter and it proved to be one of the most pivotal events leading up to and causing the Revolution.

In the letter, Adams particularly attacked Parliament's taxation without representation and the taking of colonial officials' salaries away from the colonial assembles, thus making them puppets of Parliament. Adams recognized Parliament's authority to make law for the Empire, but emphasized that it could not violate their rights as British citizens.

Samuel Adams

Samuel AdamsHe did not advocate that the colonies should be represented in Parliament, either, stating that Parliament was too far away and it would be impractical for the colonies to be adequately represented there. Instead, he said they should stick with the system that was in place since the colonies were first started, which was that they each had their own locally elected assemblies and those bodies were the only ones who had the legal authority to tax the colonists.

You can read the Massachusetts Circular letter of February 11, 1768 here. A circular letter, by the way, is so named because it is a letter that is intended to be circulated.

The letter was received positively in the other colonies. Some of them adopted the Massachusetts Circular letter as their own. Others published resolutions approving of the principles stated in the letter. Several colonies sent letters of complaint to the King. Pennsylvania and Virginia sent letters to Parliament, though the other colonies did not because they thought it would imply that Parliament had authority to tax them. The Virginia House of Burgesses also sent a circular letter to the other colonies urging them to resist any illegal activities of Parliament.

John Hancock

John HancockThe Liberty incident

In April of 1768, officials had demanded to search a ship owned by John Hancock. Hancock refused to let the officials board the Lydia because they did not have a writ of assistance. Later on, one of the officials snuck on board and was forcibly removed by Hancock's employees. Some view this as the first act of resistance of the Revolutionary War. The matter was investigated, but Jonathan Sewell, the Attorney General dropped the charges.

In May, another Hancock ship, the Liberty was confiscated by Boston customs officials when they believed goods had been smuggled off the ship without the proper duty being paid. Another riot ensued and the customs officials were pelted with rocks and other items. The customs office was heavily damaged and the personal property of some of the officials was damaged.

These officials fled the city and boarded the HMS Romney, which took them to Castle William, the British fort on Castle Island southeast of the city. The Liberty was impressed into use by the customs service to capture other smugglers and was destroyed by a rioting mob in Rhode Island the following year. As a result of the violence against the customs commissioners, they requested more military protection in the city.

Hillsborough responds to the Circular LetterWills Hill, the Earl of Hillsborough, was made the first Secretary of State for the Colonies in February 1768. The position was created specifically to deal with the growing rebellion in America, but also managed Britain's other colonies.

Wills Hill 1st Marquis of Downshire and Earl of Hillsborough

Wills Hill 1st Marquis of Downshire and Earl of HillsboroughThe Massachusetts Circular Letter alarmed Hillsborough sufficiently enough that he began to worry about a full-blown rebellion. After consulting with the King and his advisers, Hillsborough ordered the Massachusetts Assembly to revoke its letter and ordered Governor Francis Bernard to dissolve the Assembly if they refused.

Secretary Hillsborough also realized that the rebellion was spreading. He sent his own circular letter, with the consent of the King, to all the other governors and ordered them to dissolve their respective assemblies if they responded favorably to the Massachusetts Circular Letter.

On June 30, the Massachusetts Assembly met and voted 92 to 17 to defy Secretary Hillsborough's order, keeping the Circular Letter in effect. The vote was followed by celebrations in Boston and Paul Revere was even commissioned by the Sons of Liberty to create a silver punch bowl to commemorate the occasion!

In response, Governor Bernard dissolved the Assembly the following day, which led to mass riots in Boston. The citizens of Massachusetts had no legislature by which to govern or to whom they could express their grievances. Royal officials of all types were attacked and rioters destroyed government offices. Boston began to fall into anarchy.

Hillsborough's threat letter to the other colonies was too late. Many had already begun to act on the Massachusetts letter. Hillsborough's letter only emboldened and unified them as the various colonies began publishing resolutions declaring that Parliament had no authority to dissolve their elected assemblies. As assemblies responded to the Massachusetts letter positively, the various governors took action against them.

Maryland's legislature was suspended by Governor Horatio Sharpe in June. New Jersey's assembly was dissolved in July. The assemblies of North Carolina, South Carolina and Rhode Island were dissolved in November, Georgia's and New York's in December and Virginia's in May of the next year. When the assembly of South Carolina was dissolved, the citizens of Charleston celebrated by burning the 17 Massachusetts men who voted to revoke the Circular Letter in effigy in a patriotic celebration.

You can read the Hillsborough Circular Letter here.

Economic boycotts begin againHillsborough's letter had the unintended consequence of unifying opposition to Parliament in the colonies. It also made one thing clear to the colonists, Parliament was not going to back down. The colonists' response was to go back to an effective tactic they had used in their efforts to repeal the Stamp Act... an economic boycott.

During the Stamp Act crisis, colonists organized an effective boycott of British goods that brought the British economy to a standstill. Manufacturers across England slowed down or stopped production and laid off tens of thousands of workers. Conditions were so bad that rioting for simple necessities and more consistent wages became commonplace in England and people began to lobby their members of Parliament to repeal the Act. The economic boycott was the probably the single most effective strategy the colonists used against the Stamp Act.

Since Parliament was not responding to their remonstrances against the Townshend Acts, the colonists reverted to this old strategy again in the fall of 1768. Notice that a year and a half had gone by since the Townshend Acts were passed, so this was not their first strategy.

The Massachusetts State Assembly led the way with a letter to the other colonies asking them to join a boycott of British goods to begin on January 1, 1769. Many colonies and cities followed suit and joined them. This boycott was never as broadly supported as the one during the Stamp Act crisis, partly because the colonies were already in an economic recession, but it may have reduced British imports by 40 or 50 percent.

Even though this boycott was not as effective as the one during the Stamp Act crisis, it had its effect and British merchants and their workers began lobbying Parliament for repeal once again.

British troops occupy BostonSecretary Hillsborough had already decided to send troops to Boston by the time the Liberty incident occurred to deal with the growing insurrection and lawlessness. The riots that began when the Assembly was dissolved only enflamed matters even more. In September, the colonists discovered that four regiments of soldiers would soon be arriving.

The first British soldiers began to disembark in Boston on October 1, 1768. It was the arrival of these troops that eventually led to the Boston Massacre.

Troops were housed in public places such Faneuil Hall, the Boston Common and the public "poorhouse," a public place which cared for destitute people, in accordance with the Quartering Act. Troops would monitor public events and highly trafficked areas. Having soldiers in such places, always in sight of the public caused a great deal of anger and resentment in the colonists toward the occupying British soldiers. Verbal abuse, stones and trash were frequently aimed at the soldiers, who had strict orders not to harass or fight with the colonists.

Boston Massacre engraving by Paul Revere

Boston Massacre engraving by Paul RevereOver the course of the next eighteen months, incidents between soldiers and colonists were frequent. In February 22, 1770, a protest was organized in front of the shop of Theophilus Lillie, a loyalist who had violated the economic boycott. Certain officials were involved with trying to break up the protest, including Ebenezer Richardson, an employee of the Customs Service.

The crowd turned on those trying to break up the protest. They attacked Richardson's home and began throwing stones at the house, one of which hit Richardson's wife. A terrified Richardson fired his gun into the crowd to try to get them to disperse. An 11 year old boy named Christopher Seider, who was the son of German immigrants, was hit in the arm and the chest and he died later that day from his wounds.

Seider's death was a lightning rod in the community of Boston. His funeral was arranged by Samuel Adams and was attended by over 2,000 people. The community was so aroused that harassment of British troops increased. This was one of the primary events that led to the Boston Massacre, only eleven days after Seider's death, when soldiers fired upon a group of citizens who were harassing and threatening them and throwing snowballs and chunks of ice at them.

Ebenezer Richardson was tried and found guilty of murder for Seider's death, but he was given a royal pardon for doing it in self-defense. He was also given a promotion in the Customs Service for his actions in supporting the British government. Richardson's pardon and promotion were viewed with outrage by the colonists, enflaming them all the more.

Townshend Acts repealedWilliam Pitt, the Earl of Chatham was made Prime Minister for a short time after the Marquess of Rockingham resigned. Pitt was in continuous ill health though and resigned after only three months and was replaced by Augustus Fitzroy, the Duke of Grafton in the fall of 1768.

Fitzroy was one of William Pitt's supporters, but was widely criticized for his inability to counter the growing threats to Britain's dominant position in the world, including in the colonies. The British troops arrived in Boston only two weeks before he took office. Protests and riots in the colonies marked the whole of his first year in office.

Lord Frederick North

Lord Frederick NorthIn January, Fitzroy resigned and Lord Frederick North, the 2nd Earl of Guilford was named Prime Minister in his place. Lord North would be the Prime Minister through most of the American Revolution.

North realized the Townshend Acts' taxes were a problem and advocated for their repeal from the start of his administration, but he recommended keeping the tax on tea for the simple reason of reminding the colonists that Parliament did have the right to tax them. In spite of his initial wisdom in advocating for the Townshend Acts' repeal, Lord North would go on to support a series of devastating acts and measures that plunged the colonies into war with Britain.

On March 5, 1770, the same day as the Boston Massacre, Parliament began debating a repeal of the Townshend Act taxes. The boycotts had taken effect and members were being pressed by their British constituents to repeal the tax so they could begin exporting their goods to the Americas and get back to work again.

Some parties wanted all the taxes repealed, but in the end Parliament agreed to remove all the taxes except those on tea. A vote taken to remove the tea tax was defeated by a vote of 204 to 142. The final vote to repeal the rest of the taxes was made on April 9, 1770 and it was signed into law by King George III on April 12, 1770.

The Cascade of events leading to the war after repeal of the Townshend ActsThe repeal had little practical effect. The colonists of course were not pleased that the tea tax remained. The idea that Parliament could tax them without representation remained a point of contention with them. There was a continual upward spiral of strife, protesting, acts of violence against officials and other types of resistance for the next several years as officials began to enforce the Townshend Acts and more and more incidents occurred, clashes with smugglers increased and citizens faced prosecution for their smuggling activities.

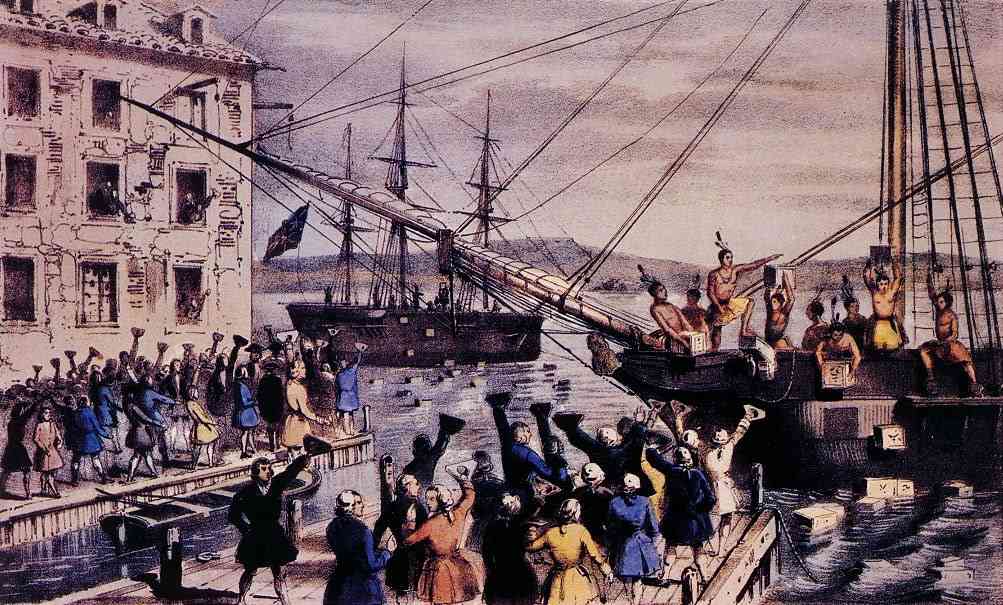

Boston Tea Party May 5, 1770

Boston Tea Party May 5, 1770The Boston Massacre occurred just as the Townshend Acts were being repealed. John Hancock's ship, Liberty, which had been impressed into the customs service during the earlier alleged smuggling incident, was attacked and burned in Rhode Island in July 1769, after capturing two alleged smuggling ships. This was one of the first overt acts of violence of the American Revolution. In June 1772, a customs ship named the Gaspee was attacked, looted and burned, also in Rhode Island, as it chased smugglers.

Parliament reinforced the tea tax with the Tea Act of 1773 further angering the colonists, who responded by dumping a shipload of British tea into Boston Harbor in December of that year in the incident known as the Boston Tea Party.

An outraged Parliament then passed the Coercive Acts, called the Intolerable Acts by the colonists, from March to June, 1774. These Acts closed the port of Boston until the tea was paid for, made most government offices in Massachusetts royally appointed positions, shut down many town assembly meetings and moved trials of government officials out of Massachusetts if they could not get a "fair" trial there.

The colonists responded by forming their First Continental Congress in September of 1774. The outbreak of the war finally occurred in Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775.

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments