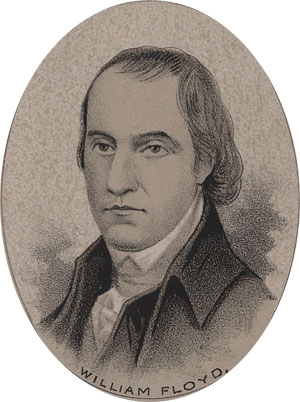

William Floyd of New York

Wales, in Great Britain, was the fatherland of William Floyd. His grandfather came hither from that country in the year 1680, and settled at Setauket, on Long Island. He was distinguished for his wealth, and possessed great influence among his brother agriculturists.

The subject of this memoir was born on the seventeenth day of December, 1734. His wealthy father gave him every opportunity for acquiring useful knowledge. He had scarcely closed his studies, before the death of his father called him to the supervision of the estate, and he performed his duties with admirable skill and fidelity. His various excellences of character, united with a pleasing address, made him very popular; and having espoused the republican cause in opposition to the oppressions of the mother country, he was soon called into active public life.

Mr. Floyd was elected a delegate from New York to the first Continental Congress, in 1774, and was one of the most active members of that body. He had previously been appointed commander of the militia of Suffolk County; and early in 1775, after his return from Congress, learning that a naval force threatened an invasion of the Island, and that troops were actually debarking, he placed himself at the head of a division, marched toward the point of intended debarkation, and awed the invaders into a retreat to their ships. He was again returned to the General Congress, in 1775, and the numerous committees of which he was a member, attest his great activity. He ably supported the resolutions of Mr. Lee, and cheerfully voted for and signed the Declaration of Independence.

While attending faithfully to his public duties in Congress, he suffered greatly in the destruction of his property and the exile of his family from their home. After the battle of Long Island, in August, 1776, and the retreat of the American army across to York Island, his fine estate was exposed to the rude uses of the British soldiery, and his family were obliged to seek shelter and protection in Connecticut. His mansion was the rendezvous for a party of cavalry, his cattle and sheep were used as provision for the British army, and for seven years he derived not a dollar of income from his property. Yet he abated not a jot in his zeal for the cause, and labored on hopefully, alternately in Congress and in the Legislature of New York.1 Through his skilful management, in connection with one or two others, the State of New York was placed, in 1779, in a very prosperous financial condition, at a time when it seemed to be on the verge of bankruptcy. The depreciation of the continental paper money2 had produced alarm and distress wide-spread, and the speculations in bread-stuffs threatened a famine ; yet William Floyd and his associates ably steered the bark of state clear of the Scylla and Charybdis.

On account of impaired health, General Floyd asked for and obtained leave of absence from Congress, in April, 1779, and in May he returned to New York. He was at once called to his seat in the Senate, and placed upon the most important of those committees of that body, who were charged with the delicate relations with the General Congress.

In 1780 he was again elected to Congress, and he continued a member of that body until 1783, when peace was declared. He then returned joyfully, with his family, to the home from which they had been exiled for seven years, and now miserably dilapidated. He declined a re-election to Congress, but served in the Legislature of his State until 1778, when, after the newly adopted Constitution was ratified, he was elected a member of the first Congress that convened under that charter in the city of New York, in 1789. He declined an election the second time, and retired from public life.

In 1784 General Floyd purchased some wild land upon the Mohawk, and when he retired to private life, he commenced the clearing up and cultivation of those lands. So productive was the soil, and so attractive was the beauty of that country, that in 1803 he moved thither, although then sixty-nine years old. He directed his attention to the cultivation of his domain, and in a few years, the "wilderness blossomed as the rose," and productive farms spread out on every side.

In 1800 he was chosen a Presidential Elector; and in 1801 he was a delegate in the Convention that revised the Constitution of the State of New York. He was subsequently chosen a member of the State Senate, and was several times a Presidential Elector. The last time that he served in that capacity was a year before his death, which occurred on the fourth day of August, 1821, when he was eighty-seven years of age. Mr. Floyd had always enjoyed robust health, and he retained his mental faculties in their wonted vigor, until the last. His life was a long and active one ; and, as a thorough business man, his services proved of great public utility during the stormy times of the Revolution, and the no less tempestuous and dangerous period when our government was settling down upon its present steadfast basis. Decision was a leading feature in his character, and trifling obstacles never thwarted his purposes when his opinion and determination were fixed. And let it be remembered that this noble characteristic, decision, was a prominent one with all of that sacred band who signed the charter of our emancipation, and that without this, men cannot be truly great, or eminently useful.

1 After the Declaration of Independence was adopted, the States organized governments of their own. General Floyd was elected a Senator in the first legislative body that convened in New York, after the organization of the new government, and was a most useful member in getting the new machinery into successful operation.

2 The amount of paper money issued by Congress before the close of 1779, amounted to about two hundred millions of dollars. The consequence of such an issue was a well grounded suspicion that the bills would not ultimately be redeemed; and this suspicion, at the close of 1779, became so much of a certainty, that the notes depreciated to about one fourth of their value. An attempt was made by Congress to make these bills a legal tender at their nominal value, but the measure was soon perceived to be mischievous, and they were left to their fate.

Text taken from "Biographical Sketches of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence" by BJ Lossing, 1848

Return to Founding Fathers Page

Revolutionary War and Beyond Home

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments