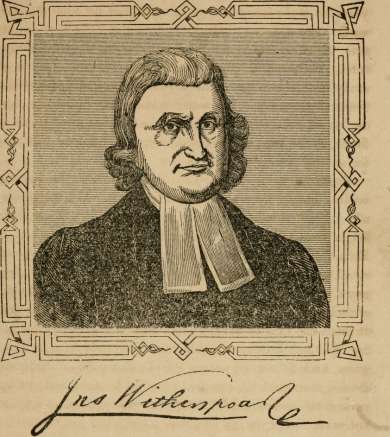

John Witherspoon of New Jersey

John Witherspoon was born in the parish of Yester, near Edinburgh, Scotland, on the fifth of February, 1722. He was a lineal descendant of the great reformer John Knox. His father was a minister in the Scottish church, at Yester, and was greatly beloved. He took great pains to have the early education of his son based upon sound moral and religious principles, and early determined to fit him for the gospel ministry. His primary education was received in a school at Haddington, and at the age of fourteen years he was placed in the University of Edinburgh. He was a very diligent student, and, to the delight of his father, his mind was specially directed toward sacred literature. He went through a regular theological course of study, and at the age of twenty-two years he graduated, a licensed preacher. H e was requested to remain in Yester, as an assistant of his father, but he accepted a call at Beith, in the west of Scotland, where he labored faithfully for several years.1

From Beith he removed to Paisley, where he became widely known for his piety and learning. He was severally invited to take charge of a parish and flock, at Dublin, in Ireland ; Dundee, in Scotland; and Rotterdam, in Holland; but he declined them all. In 1766 he was invited, by a unanimous vote of the trustees of New Jersey College, to become its president, but this, too, he declined, partly on account of the unwillingness of his wife to leave the land of her nativity. But being strongly urged by Richard Stockton (afterward his colleague in Congress, and fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence), then on a visit to that country, he accepted the appointment, and sailed for America. He arrived at Princeton with his family, in August, 1768, and on the seventeenth of that month he was inaugurated president of the College. His name and his exertions wrought a great change in the affairs of that institution, and from a low condition in its finances and other essential elements of prosperity, it soon rose to a proud eminence among the institutions of learning in America.2

When the British army invaded New Jersey, the College at Princeton was broken up, and the extensive knowledge of Dr. Witherspoon was called into play in a vastly different arena. He was called upon early in 1776, to assist in the formation of a new Constitution for New Jersey,3 and his patriotic sentiments and sound judgment were there so conspicuous, that in June of that year, he was elected a delegate to the General Congress. He had already formed a decided opinion in favor of Independence, and he gave his support to the resolution declaring the States free forever.4 On the second of August, 1776, he affixed his signature to the Declaration.

Doctor Witherspoon was a member of Congress from the period of his first election until 1782, except a part of the year 1780, and so strict was he in his attendance, that it was a very rare thing to find him absent. He was placed upon the most important committees, and intrusted with delicate commissions. He took a conspicuous part in both military and financial matters, and his colleagues were astonished at the versatility of his knowledge.

After the restoration of peace in 1783, Doctor Witherspoon withdrew from public life, except so far as his duties as a minister of the gospel brought him before his flock. He endeavored to resuscitate the prostrate institution over which he had presided. Although to his son-in-law, Vice President Smith, was intrusted the active duties in the effort, yet it cannot be doubted that the name and influence of Doctor Witherspoon were chiefly instrumental in effecting the result which followed. After urgent solicitation, he consented to go to Great Britain and ask for pecuniary aid for the college. In this movement his own judgment could not concur, for he knew enough of human nature to believe that while political resentment was still so warm there against a people who had just cut asunder the bond of union with them, no enterprise could offer charms sufficient to overcome it. In this he was correct, for he collected barely enough to pay the expense of his voyage.

About two years before his death, he lost his eye-sight, yet his ministerial duties were not relinquished. Aided by the guiding hand of another, he would ascend the pulpit, and with all the fervor of his prime and vigor, break the Bread of Life to the eager listeners to his message.

As a theological writer, Doctor Witherspoon had few superiors, and as a statesman he held the first rank. In him were centred the social elements of an upright citizen, a fond parent,5 a just tutor, and humble Christian; and when, on the tenth of November, 1794, at the age of nearly seventy-three years, his useful life closed, it was widely felt that a "great man had fallen in Israel."

1 While he was stationed at Beith, the battle of Falkirk took place, between the forces of George the Second, and Prince Charles Stuart, during the commotion known as the Scotch rebellion, in 1745-6. Mr. Witherspoon and others went to witness the battle, which proved victorious to the rebels : and he, with several others, were taken prisoners, and for some time confined in the castle of Doune.

2 For a long time party feuds had retarded the healthy growth of the College and its finances were in such a wretched condition, that resuscitation seemed almost hopeless. But the presence of Doctor Witherspoon silenced party dissentions, and awakened new confidence in the institution ; and the province of New Jersey, which had hitherto withheld its fostering aid, now came forward and endowed professorships in it.

3 After the abdication of the Colonial Governors, in 1774 and 1775, provisional governments were formed in the various States, and popular Constitutions were framed, by which they were severally governed under the old confederacy.

4 He took his seat in Congress, on the twenty-ninth of June, 1776. On the first of July, when the subject of the Declaration of Independence was discussed, a distinguished member remarked, that "the people are not ripe for a Declaration of Independence." Doctor Witherspoon observed: "In my judgment, sir we are not only ripe, but rotting."

5 Doctor Witherspoon was twice married. By his first wife, a Scottish lady, he had three sons and two daughters. One of the latter (Frances) married Doctor David Ramsay, of South Carolina, one of the earliest historians of the American Revolution. She was a woman of extraordinary piety, and the memoirs of but few females have been more widely circulated and profitably read, than were hers, written by her husband.

Text taken from "Biographical Sketches of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence" by BJ Lossing, 1848

Return to Founding Fathers Page

Revolutionary War and Beyond Home

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments