Betsy Ross Flag

The Betsy Ross Flag is probably the most well known of the many American Revolutionary War Flags. The familiar 13 red and white stripes and the blue field with 13 stars in a circle is commonly seen on patriotic memorabilia, books, artwork, tv shows and more. The facts of the Betsy Ross Flag legend come to us primarily from a paper read by her grandson William Canby to the Historical Society of Philadelphia in March, 1870. The story was published by Harper's New Monthly Magazine in July 1873 and from that point entered into American folklore. Shortly afterwards, it began to appear in school textbooks. Scholars are not completely convinced about the authenticity of the legend however. Read more about the history of the Betsy Ross Flag below.

Betsy Ross Flag legend

William Canby was the grandson of Betsy Ross. He was only 11 years old when his grandmother died, but he reported that he heard the details of her making the first American Revolution flag from her own mouth. He also reported hearing other family members say they had heard her talk about it as well, including two of her daughters and one niece, all three of whom were still living at the time of Canby's speech and whom had also signed written affidavits of the fact.

Canby says that his grandmother, Betsy Ross, made the following claims: Some time in May, 1776, three men came to her shop on Arch Street and asked if she could sew a flag according to a design they gave her. The three men were George Washington, Robert Morris and George Ross.

Robert Morris was a delegate to Congress from Pennsylvania. Morris has been called the "Financier of the Revolution." He was a prominent and active founding father, signing the Declaration of Independence and using his huge fortune to help finance the Revolutionary War.

George Ross was also a member to Congress from Philadelphia. He was prominently involved in the American Revolution, being a chief player in the creation of the Pennsylvania Constitution and signing the Declaration of Independence. To give you an idea of how popular and well-known George Ross was, when the Pennsylvania Provincial Legislature was choosing its delegates to send to the second Continental Congress in 1774, George Ross received the second highest number of votes, only behind Benjamin Franklin, who received the most.

Betsy Ross 1777 by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

Betsy Ross 1777 by Jean Leon Gerome FerrisGeorge Ross was also the uncle of John Ross, Betsy's husband who had died in an explosion in January, 1776, as he guarded munitions for the Pennsylvania militia. This left the 24 year old Betsy, who as yet had no children, alone and overwhelmed financially as she tried to make ends meet. The arrival of the three men with the secret flag mission changed her financial fortune forever. The flag she created began a career of flag making that lasted decades and she never had to look for employment again.

George Washington was a personal friend of Betsy Ross according to the testimony of several of her descendants. George Washington and Betsy Ross both attended Christ Church in Philadelphia. Moreover, their pews were right next to one another. At that time people had regular seats in church where they would always sit, so they would have seen one another every time they attended church and both were regular church goers.

According to Betsy Ross' descendants, George Washington was a regular guest at Betsy's home, coming there to socialize, as well as for her services as a seamstress. Ross claimed to have embroidered ruffles for Washington's shirts and cuffs. It was partly due to Washington's friendship with her that the committee chose to call on her, as well as Mr. Ross' relation to her by her husband.

When the three men arrived at Betsy Ross' house, they told her they were appointed to a secret committee appointed to create a new flag for the united colonies. They asked her if she thought she could make a flag and she replied that

"she did not know but she could try; she had never made one but if the pattern were shown to her she had not doubt of her ability to do it."

Learn more about Betsy Ross' personal life at our Betsy Ross Facts page.

Betsy Ross was a seamstress and upholsterer. She and her husband owned a furniture business where they would upholster chairs and such things. She continued in this business after her husband's death, becoming particularly known as a seamstress, making such things as curtains, bedspreads, clothing, pillows, embroidery, etc. The war caused prices to skyrocket and the colonial economy was in a severe downturn causing many colonists to forego luxury items and even common items that a seamstress would make. This put many seamstresses into severe economic hardship. Consequently, it was common for seamstresses to take on additional work creating flags, uniforms and tents for the soldiers. There were many seamstresses that we know of in Philadelphia who created flags for the war effort.

Betsy Ross House Philadelphia

Betsy Ross House PhiladelphiaBetsy Ross took the gentlemen to her parlor behind her shop where George Ross produced a drawing of the proposed design. It is not known who prepared this design, or what it looked like exactly. After examining the proposal, Betsy Ross made several suggestions as to how to improve the design and make it easier to manufacture.

All of her suggestions are not known, but one had to do with the shape of the flag. Apparently the design was not in the traditional shape of a flag, but was actually a square. Ross told them the width of the flag should be one third longer than its height. The second suggestion was that the stars should be put into a pattern such as a circle or a star. The drawing had them spread around the field of blue randomly. Her third suggestion became her most important contribution to the flag. The stars in the proposed design were six-pointed stars, rather than five-pointed stars. Betsy Ross told the gentlemen that five-pointed stars were much easier to make and proceeded to show them how to create a simple five-pointed star out of a piece of cloth with several folds and a single snip.

The men were quite impressed with her ingenuity and George Washington sat down with a pencil and redrew the design. According to Betsy Ross, the final decision on the design was completely in the hands of George Washington and the other two were merely observers. After the design was decided upon, it was sent to William Barrett, a local painter, to create a watercolor painting of the proposed flag, which Betsy Ross could use for a pattern.

The three men then suggested to Betsy Ross that she go to the shop of a particular shipping merchant at a certain hour who would give her a flag that she could use as a model. Betsy Ross went the following day to meet the merchant and received a used flag from him to use as her pattern, examining it to see exactly how it was sewn and stitched together.

According to Ross, the secret flag committee had also drawn up several other designs, two or three of which had been given to other local seamstresses to create. Some time in late May or early June, Betsy Ross finished her flag and took it to the shipping merchant who had it hoisted on one of his ships, to the delight of local passersby.

George Ross

George RossThe Betsy Ross Flag was then taken directly to the State House, where it was presented to Congress with a report from the committee. The following day, George Ross returned to Betsy's house and told her the Congress had accepted her design. He said they were ordering as many as she could produce and wanted her to begin immediately. Betsy Ross was delighted at first because she had been in such a dire financial position after her husband died, but after Mr. Ross left, she began to worry about how she would buy the materials to create so many flags. The cost of raw goods such as silk (which is what flags were made of at the time) and thread had skyrocketed due to the war. She didn't have any money to buy the materials and most merchants were doing business solely on a cash basis. Even if she could find one who would sell the goods on credit, she was poor and it was unheard of for merchants to extend credit to someone in her financial position.

As Betsy sat worrying about how she would fulfill the order from Congress for as many flags as she could produce, George Ross returned to the store and apologized that he forgot to mention something to her. Knowing that she was in a hard place financially, he gave her 100 pounds and told her she could use his credit to buy any needed supplies. Betsy rejoiced that she would now be able to begin working on as many flags as she could make.

Betsy Ross began producing flags and continued making them literally for 50 years. Many of her family members took part in the flag making over the years and her daughter Clarissa carried on the business for another 30 years after Betsy's death in 1836. According to Harper's New Monthly Magazine in July 1873, which published the Betsy Ross Flag story to a national audience for the first time, Clarissa gave up the business at the outbreak of the Civil War because she was a member of the Society of Friends, the Quakers, who were against war under any circumstances and she did not want her flags to be used for the war.

The Betsy Ross Flag - Truth or Legend?

Many historians have questioned this version of the creation of the first American Revolution Flag. The reason for the questions is that many of the statements made by William Canby, Betsy Ross' grandson, in his speech to the Historical Society of Philadelphia, cannot be verified from other sources.

Most of the facts of the story exist only in the testimony of William Canby and three other relatives of Betsy Ross'. In other words, there is no independent documentation from other sources to corroborate the story. Some people have gone so far as to accuse Canby of fabricating the story for personal fame. They say the story can not be true because it cannot be proven. A better assessment would probably be that the story may not be true because it cannot be proven, but on the other hand it may be true, just not provable. Many of the facts are simply unknown. In the following paragraphs, you will find a list of arguments both for and against the Betsy Ross Flag story:

George Washington

George Washington* George Washington was appointed Commander-in-Chief on June 15, 1775. Some scholars have suggested that, in this position, it is unlikely that he would have been appointed to a committee tasked with something so inconsequential as picking out a flag. While it is true that Washington was Commander-in-Chief at this time, we know from his personal letters that he was in Philadelphia during the time of May to early June 1777. This time frame matches Betsy Ross' testimony exactly. In addition, Congress appropriated 50,000 pounds during this time for the acquisition of "sundry articles" for the Continental Army. It would not be unreasonable to think that Washington would have purchased flags for the army. Indeed, it is well known that George Washington raised the British Grand Union flag, modified with white stripes, at the Battle of Cambridge in January 1776 and that the flag was misinterpreted by the British as a sign of surrender. This alarmed George Washington. He wrote of the incident in a letter a few days later to Joseph Reed and made several statements indicating that independence was probably inevitable. You can read this letter from George Washington to Joseph Reed of January 4, 1776 here. This means Washington knew that independence would probably eventually be declared and that he knew a new flag would be necessary for the colonies. So, Washington had the creation of a new flag in mind for several months, was in town at the time Betsy Ross indicated and Congress appointed 50,000 pounds for army supplies at the same time. All of these facts make Betsy Ross' story seem plausible.

* There is no existing record of the first American flag transaction within Betsy Ross' own records, even though she was a thorough recordkeeper.

* There is no independent written evidence that George Washington and Betsy Ross knew one another. However, as was stated before, Washington and Ross likely knew one another from church, as their pews, where each regularly sat, were right next to one another. This makes Ross' story seem plausible. In addition, George Ross, who was Betsy's late husband's uncle, undoubtedly knew her and her situation well. Finally, George Ross' sister married George Read, another signer of the Declaration of Independence from Delaware, which is right across the river from Philadelphia. This means that George Read was another uncle of John Ross, Betsy's late husband. So there were two uncles of Betsy's husband in the Continental Congress. George Read was in frequent communication with both George Ross and George Washington and may have served in more government offices than any other founding father. Beyond that, George Ross' sister Mary was married to a gentleman named Mark Bird. Mark's sister Rachel married James Wilson, yet another signer of the Declaration of Independence. The intricate relations of this circle of people makes it highly plausible that Betsy Ross knew each of the players intimately and had regular relations with them.

Francis Hopkinson

Francis Hopkinson* Neither George Washington, George Ross, Robert Morris, nor any other member of the Continental Congress made any reference to a national flag in their correspondence Click for larger image Francis Hopkinson in 1777. The first significant mention of such a flag came from New Jersey signer of the Declaration of Independence Francis Hopkinson in 1780 when he submitted a bill to Congress asking for payment for creating a national flag. As a member of the Naval Marine Committee, Hopkinson is known to have contributed to the designs of several national symbols, including the Treasury Seal, the Great Seal and the Continental Currency. Flags were most commonly used on ships, so it would have been normal for the Marine Committee to have jurisdiction over such a decision. But, Congress did not approve payment of Hopkinson's bill, saying that many other's had contributed to the design as well. There is no drawing showing what flag Hopkinson designed. Though the design with stars in the 3-2-3-2-3 layout is often attributed to him, there is no concrete proof. Some scholars have speculated that Ross' flag came first and Hopkinson's later. Again, the Flag Resolution did not specify the layout of the stars, so many differing designs were used, but there is no written record showing which came first.

* Because Congress' Flag Resolution did not occur until 1777, many scholars have

said that any suggestion of a previously approved flag is simply not true. Betsy Ross

said she created the flag with the circular star pattern a year before this. This

seems at first to disprove Ross' story. However, Congress was known to have appointed

committees in secret at times, the details of which were not included in

official records, so the idea that a secret committee existed is not out of the question.

More likely, Congress was extremely busy at the time, sometimes appointing as many as

six committees to oversee various details of the Revolutionary War in a single day.

With so much activity going on, it is likely that accurate records were not always

kept. A detail as minor as what the flag would look like may not have been an

extremely important issue compared with other decisions the Congress was making. It

is not unreasonable to imagine that members of the Marine Committee, who all knew

Betsy Ross, could have walked a few blocks to her house to talk with her and been

back to Congress in an hour. In short, the fact that written records of the flag's

creation do not exist does not prove that this version did not happen. Betsy Ross'

story is at least plausible, just not proven.

* Why is there mention of the Marine Committee and the State Marine Board being involved in the creation of flags? In colonial times, flags were used to identify different regiments of military soldiers, however, the use of flags to identify ships was even more prevalent. The use of flags for identifying the origin of ships goes back to medieval times and may even predate their use on the battlefield. This is the reason that Washington and Ross would have sent Betsy to a shipping merchant for the flag to be used as her model and why she first took the flag back to this merchant to try it out on a ship. It also explains why Frances Hopkinson would have had something to do with designing flags as a member of Congress' Marine Committee.

* It is unsure whether the revolutionaries considered the 13 star flag as a flag for the entire Continental Army, or for the navy only. The original Flag Resolution of 1777 was submitted to Congress by the Marine committee, so the flag may have been considered solely as a marine emblem. As long as two years afterwards, it was undecided what the actual design of the flag for the army was, as indicated in a letter from Richard Peters at the Board of War to George Washington at Middlebrook, New Jersey on May 10, 1779, in which Peters asks Washington what the official standard is. Read the letter from Richard Peters to George Washington of May 10, 1779 here.

* In a second letter from the Board of War, dated September 3, 1779, the Board sends several flag drawings to Washington asking for his opinion. The Board suggests that a different flag be used for the Marines than for the ground troops, the suggested Marine flag having a serpent in the middle of it, along with the British Union in the canton (upper left corner). This would be in line with the use of the serpent on the First Navy Jack flag that was previously used by the Marines. No drawing has survived though to indicate exactly what Washington and Peters were talking about. All of this indicates though, that people were still unsure what the official flag was, even though the Flag Resolution was passed two years before. Read the September 3, 1779 letter from Richard Peters to George Washington here and read George Washington's reply to Richard Peters of September 14, 1779 here.

* Everyone agrees that the Flag Resolution did not specify a layout for the flag. Some scholars believe the reason for this was that the Betsy Ross Flag was already in use and the resolution was merely confirming the design. In other words, everyone was already familiar with the design, so a more detailed description was unnecessary. This is of course, speculation, but again, it is plausible and cannot be disproved either.

* There is a painting by amateur Philadelphia artist Ellie Wheeler dated 1851 that depicts Betsy Ross talking about the flag with the three men of the secret committee. If this painting is authentic, it means the story related by Canby was known before the Civil War and nearly twenty years before Canby told it. If this is the case, the story was not a fabrication by Canby. A fine arts appraiser known as Raymond M. Spiller and Associates, Inc. appraised the painting in 1985 and said the painting was indeed authentic, dating it to the mid-nineteenth century. Some historians and art experts have refuted this appraisal however. They say the alleged Wheeler painting is actually a less well executed copy of a painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris dated from sometime between 1900 and 1920 when Ferris created a series of paintings commemorating the founding period. Due to the disagreement between art historians, it cannot be determined which came first. If the Wheeler painting came first and the Ferris painting is a later reproduction, the Betsy Ross story was definitely a commonly known story in the public for many years before Canby's speech. If the Ferris painting came first and the Wheeler painting is the reproduction, the painting cannot be used to verify the Betsy Ross Flag story. The two paintings are obviously identical, except for the skill level, so the question is which came first. So... as with most of the other matters related to the Betsy Ross Flag story... nothing is known for sure!

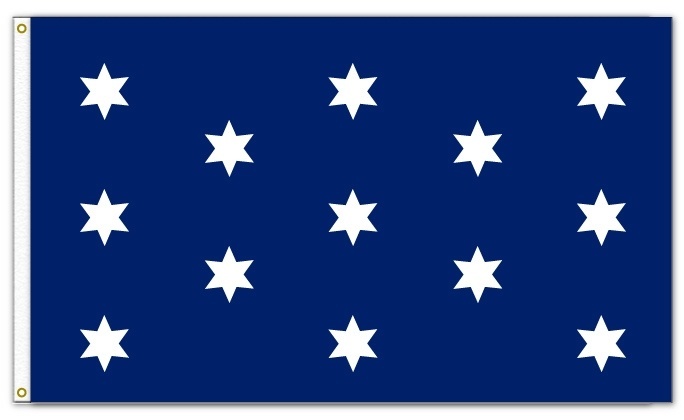

George Washington's Commander-in-Chief Flag

George Washington's Commander-in-Chief Flag* Another point that favors Betsy Ross' Flag story is that George Washington is known to have favored six-pointed stars. Flags in that era frequently had six, seven or eight points. George Washington personally designed his own Commander-in-Chief Flag, also known as the Washington Headquarters Flag.

This flag contained 13 six-pointed stars arranged in a vertical staggered pattern. The six pointed star is a commonly used symbol in Freemasonry, which society George Washington was a part of and is also known as the Star of David, representing the Jewish people or the nation of Israel. Washington is known to have been a strong supporter of the Jewish people. All of this lends to the authenticity of Betsy Ross' testimony that Washington would have come to her with an original design including six-pointed stars. Critics say the point proves exactly the opposite, that Washington's known affinity to six-pointed stars would make it unlikely that he would have approved of a five-pointed star.

George Washington Family Coat of Arms

George Washington Family Coat of Arms* George Washington's family coat of arms included a shield of red and white stripes with 3 five-pointed stars above them. This may have been the origin for the white stripes added to the British Red Ensign flag and would provide an alternate source for the five-pointed stars if the Betsy Ross story is to be discounted. You will see this coat of arms on the Purple Heart medal, an award that George Washington created. Another possible source for the red and white stripes is the Sons of Liberty flag used in Boston. That Washington was aware that a new flag was necessary after the misinterpretation by the British at the Battle of Cambridge is solidly documented. So this could provide a plausible explanation for the design of the flag, but would discount the Betsy Ross flag story, at least in the part about her suggesting the five points, though it wouldn't refute her making the flag.

Francis Hopkinson Flag aka the 13 Star Flag

Francis Hopkinson Flag aka the 13 Star Flag* One of the other main contenders for the honor of creating the first American flag is New Jersey signer of the Declaration of Independence Francis Hopkinson. Hopkinson was a prolific artist who made many drawings, poems, songs and more. In the vast majority of Hopkinson's works, including the creation of flags for many different governmental bodies, he used six-pointed stars. The Francis Hopkinson Flag to the left is normally attributed to him. Late in his career, there are some instances where Hopkinson began using five-pointed stars, but these are much later in his body of work. For years and years, he used only the six-pointed design. In the eyes of some historians, this is another fact that casts doubt on the idea that Hopkinson actually created the first flag with five-pointed stars, removing one of the main contenders for the honor and leaving Betsy Ross as the better candidate.

* George Ross was not actually a member of Congress during the time frame in question. He had been a member of the First Continental Congress in 1774 and was later appointed to the Second Continental Congress on July 20, 1776. This means that Ross did not vote for independence on July 2 or to adopt the Declaration of Independence on July 4. He was in position, however, to sign the document, which was done on August 2. At first glance this seems to refute Canby's testimony. However, if you read Canby's testimony closely, he did not say that Ross was a member of Congress at the time the committee came to Betsy Ross' house. He only says that George Ross was a member of Congress. Since it was a well known fact in years after that George Ross had been a member of Congress, it is not unreasonable to assume that he would be called "a member of Congress" by someone talking about him. Canby was not referring to the time frame, but to the person. George Ross was intricately involved in the independence effort for the duration of the war, even though he was not specifically in Congress from May to June that year. Ross was involved in the Pennsylvania militia, the creation of Pennsylvania's Constitution, was a delegate to Pennsylvania's rebel congress, etc. In addition, he was a close associate of many of the members of Congress, including George Washington, Robert Morris and George Read. George Read, another uncle of Betsy Ross' late husband, was in Congress and is known to have served on a committee with Washington during this timeframe. It is not unreasonable to imagine that Washington and Read, or Washington on his own decided to approach Betsy Ross to make a flag and asked George Ross to go along because of his close relation to her. Or, perhaps they asked Ross whom he would suggest to make the flag and he suggested Betsy. Of course, the actual sequence of events from the time it was decided that a flag was necessary, who made the decision and how they got to Betsy cannot be determined for sure, but, nonetheless, all of the characters in play suggest several plausible scenarios that would verify Betsy's story.

Mrs. Ross and the Flag Committee from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, July, 1873

Mrs. Ross and the Flag Committee from Harper's New Monthly Magazine, July, 1873* The Betsy Ross Flag story got into the American psyche through an article on flag history published in Harper's New Monthly Magazine in July 1873. This article contains all the same facts from Canby's story, except that it places the events in 1777 instead of 1776, fitting the story neatly together with the Flag Resolution of June, 1777. It is plausible and would line up exactly with the time of the payment Betsy received from the State Navy Board for flags, but according to Betsy's relatives, she said it happened the year before. You can read the Harper's New Monthly Magazine article, National Standards and Emblems, that relates the Betsy Ross flag story here. The article is on pages 171-181 of the magazine and reviews flag history from ancient times through the Middle Ages to the rise of the British Empire. The Betsy Ross story is not mentioned until page 181. This is the first time the story was published nationally. You will need to increase the print magnification using the tool at the top of the page because the print will be too small to read otherwise.

* William Canby, Betsy Ross' grandson, prepared a paper that he read to the Historical Society of Philadelphia in March, 1870. In this story he relates that he heard Betsy tell that she made the first flag at Washington's request from her own mouth. This paper is the main source for information about the Betsy Ross Flag story. You can read The History of the Flag of the United States by William Canby here.

* Rachel Fletcher, Betsy Ross' third daughter gave a sworn affidavit on July 31, 1871 stating that she also agreed with the relevant facts related by Mr. Canby and that she had also heard the same story from Betsy's own mouth. Read Rachel's Fletcher affidavit about the Betsy Ross flag story here.

* Betsy's granddaughter Sophia B. Hildebrandt signed a sworn affidavit on May 27, 1870, that she had heard from her grandmother on frequent occasions the story of the creation of the Betsy Ross flag. Sophia was the daughter of Clarissa S. (Claypoole) Wilson and granddaughter of Betsy Ross. Clarissa was the daughter of Betsy's third husband John Claypoole. Read Sophia Hildebrandt's affidavit about the Betsy Ross flag story here.

* Margaret Donaldson Boggs, who was the daughter of Sarah Donaldson, Betsy's sister, also signed a sworn affidavit on June 3, 1870, that she had heard her aunt Betsy tell the story of making General Washington's first thirteen starred flag. Read Margaret Boggs' affidavit about the Betsy Ross flag story here.

* Samuel Wetherill was a good friend of Betsy Ross for many years. She and his son were the final two members of the Free Quaker Meeting House before they closed it. The Wetherill family tradition stated that Samuel Wetherill visited Betsy Ross shortly after she met with the secret committee from Congress. She told him what happened and showed him the five-pointed star she had cut for them. Wetherill recognized the historic importance of the moment and asked if he could have the star, which she gave him. Samuel Wetherill put the star in the family safe, which was eventually put away into storage. In 1925, the Wetherill safe was opened and Betsy Ross' five-pointed star was found. It was exhibited for many years at the still standing Free Quaker Meeting House, but has since gone missing.

* There are several accounts which indicate the Betsy Ross flag layout was in use by the fall of 1777. Some historians believe the flag was first mentioned in accounts of the Siege of Fort Schuyler in New York, also known as the Siege of Fort Stanwix, on August 2, 1777. It was allegedly described to them from soldiers who arrived to reinforce them a few days before, which fits in with the timeline, the flag design having been voted on by Congress a month earlier. One witness stated that it was important to the soldiers who took the Fort on the second to have a flag representing the colonies to fly over the conquered fort and that they made one out of their own clothes using white shirts, a blue officer's coat and red material from women's flannel petticoats. The written accounts are not completely clear and definitive though. Alfred B. Street described the stars laid out in a circle on a flag at the surrender of General Burgoyne at the Battle of Saratoga in October, 1777.

George Washington at Princeton by Charles Willson Peale

George Washington at Princeton by Charles Willson Peale* There are a few records that indicate the Betsy Ross Flag design was in use before the Flag Resolution of 1777, which would match Betsy Ross' own testimony. Charles Willson is one of the preeminent artists of colonial America. He painted many of the founding fathers and actually painted George Washington seven times. Peale's portrait of Washington called George Washington at Princeton is regarded as one of the most accurate physical likenesses of Washington. The painting depicts Washington after the Battle of Princeton, a battle at which Peale was personally present, fighting in the front line at the climax of the battle. There are several versions of this painting because Peale painted a large number of copies due to its popularity, some of which have minor differences in the details. The first one was completed in 1778. Very clearly in the background is a flag with the stars placed in a circle, but is this the Betsy Ross Flag? Or is it another flag that was personally flown by George Washington called the Washington's Commander-in-Chief Flag which was flown at his headquarters? If it is the Betsy Ross Flag, as some believe, then some scholars think it is an anachronism, meaning it is an historically accurate flag, but placed out of time. The battle took place on January 3, 1777, six months before the Flag Resolution was passed. If the 13 star design was not chosen until June of 1777, then the depiction of the Betsy Ross Flag at Princeton is clearly not accurate. But according to Betsy Ross' story, the depiction could be entirely true. Scholars point out many reasons that the painting can be trusted. Peale was obviously familiar with the scene since he was there. He is known to have been meticulous in researching the settings for his paintings. He examined the actual Hessian flags depicted at General Washington's feet so he could paint them accurately. The flags had been captured and were still in the possession of the Americans. He went to the battlefields of Princeton and Germantown to examine the local landscape for the painting. It is possible that he included a later flag for symbolism's sake, as the flag became a popular one, but his known adherence to historical detail makes it seem likely that this was the actual flag flown at the battle, clearly reinforcing the Betsy Ross flag story. Another very similar portrait of Washington called George Washington at the Battle of Princeton was commissioned by Princeton University in 1784. Washington sat again for Peale's portrait and Peale again included the Stars and Stripes with 13 stars in a circle. However, in the opinion of the editor of this site, the flag in Peale's painting is clearly the Washington's Commander-in-Chief Flag and not the Betsy Ross Flag, even though in many historical sources you will find this flag listed as a Betsy Ross Flag.

Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze

Washington Crossing the Delaware by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze* The painting Washington Crossing the Delaware by German American artist Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze is one of the most famous paintings of the American Revolutionary War. It depicts Washington crossing the Delaware River with his troops on December 25, 1776 as they launched their attack on the British at Trenton, New Jersey in the Battle of Trenton. The Betsy Ross flag is clearly depicted in the painting. Many historians discount this painting in considering the accuracy of the Canby story because the painting was not made until 1851. It was clearly not based on first hand knowledge, but was painted from folklore knowledge of the battle. However, if the Betsy Ross flag did exist at the time of the crossing, as it could have according to her story, it would also line up with Peale's portrayal of the flag at the Battle of Princeton, which happened one week later.

Surrender of General Burgoyne by Jonathan Trumbull

Surrender of General Burgoyne by Jonathan Trumbull* Jonathan Trumbull, who was an aide-de-camp to General Washington, was another famous painter during the Revolutionary War times. He painted a series of paintings that used the 13 stars and stripes flag, but in differing designs from the Betsy Ross Flag. He portrayed the stars and stripes at the Battle of Saratoga when General Burgoyne was defeated on October 1777, but with the stars in a square of 12 with one in the center. He also put the stars and stripes at the surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown in October, 1781, but in several different paintings of the same event, he put the stars in differing patterns. The Battle of Saratoga date would match several other already related facts indicating the stars and stripes were in use by the fall of 1777.

* There are numerous other paintings which use the stars and stripes, with the stars in various patterns, in numerous Revolutionary War Battles, indicating that the design was used frequently starting in the fall of 1777 and possibly earlier. Any that date earlier than the Flag Resolution of June 1777 would seem to corroborate Betsy Ross' flag story.

* The Betsy Ross Flag story has been accepted as truth by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

Betsy Ross Flag story - Summary

Betsy Ross

Betsy RossIn looking at all of the relevant evidence related to the Betsy Ross flag story, the editors of Revolutionary War and Beyond believe that the Betsy Ross legend seems the most credible of the various opinions about who created the first flag of the United States. It should be remembered though that there is no proof of the exact series of events, so no certain decision can be made. There are many related bits of information, such as the close relation of George Ross and George Read to Betsy's family, Washington's known affinity for six-pointed stars and Washington's being in Philadelphia during the time frame Betsy related that seem to lend credence to her story.

In addition to these factors, none of the facts of the story can be definitively disproved and the few points of the story which some scholars point out that create doubt about its authenticity, such as George Ross' not being a member of Congress at the time, have plausible explanations that show how they may not create doubt at all. In the case of Ross' not being in Congress at the time, the fact that he had been previously and afterwards and was intimately involved with all of the members of Congress, instead seems to bolster Betsy's story.

Betsy Ross Star

Betsy Ross StarNo matter what actually happened, the Betsy Ross flag story has been burned into the American imagination for 150 years and will undoubtedly remain an integral part of American lore for generations to come. Betsy Ross was certainly an inspiring figure, having lost two husbands to the war, carried on her own business as a widowed single mother throughout the war, manufactured tents, powder bags and blankets for American Revolutionary War soldiers and sewing flags for the American republic for decades. She will undoubtedly continue to inspire generations of Americans in the future. To learn more about Betsy Ross personal life, please read our Betsy Ross Facts page.

Can a five-pointed star actually be made with several folds and a single snip as the Betsy Ross Flag legend tells?? Yes! Learn how to make your own Betsy Ross Star here.

Learn more about other historical American Revolution Flags here.

Published October 10/19/11

Revolutionary War and Beyond Home

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments