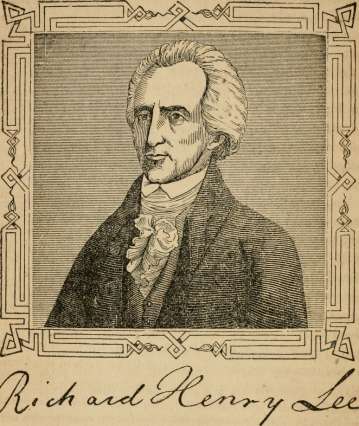

Richard Henry Lee

of Virginia

Richard Henry Lee was a scion of the noblest stock of Virginia gentlemen. Could ancestral dignity and renown add aught to the coronal that enwreathes the urn of his memory, it is fully entitled to it, for his relations for several generations were distinguished for wealth, intellect and virtue.

Richard Henry Lee was born in the county of Westmoreland, Virginia, on the twentieth day of January, 1732, within a month of time, and within a few miles space of the great and good Washington. According to the fashion of the time in the "Old Dominion," his father sent him to England, at an early age to be educated. He was placed in a school at Wakefield, in Yorkshire, where he soon became marked as a thoughtful and industrious student. Ancient history, especially that part which treats of the republics of the old world, engaged his close attention; and he read with avidity, every scrap of history of that character, which fell in his way. Thus he was early indoctrinated with the ideas of republicanism, and before the season of adolescence had passed, he was warmly attached to those principles of civil liberty, which he afterward so manfully contended for.

Young Lee returned to Virginia when nearly nineteen years of age, and there applied himself zealously to literary pursuits. He was active in all the athletic exercises of the day; and when about twenty years of age, his love of activity led him to the formation of a military corps, to the command of which, he was elected, and he first appeared in public life in 1755, when Braddock arrived from England, and summoned the colonial Governor to meet him in council, previous to his starting on an expedition against the French and Indians upon the Ohio. Mr. Lee presented himself there, and tendered the services of himself and his volunteers, to the British General. The haughty Braddock proudly refused to accept the services of those plain volunteers, deeming the disciplined troops whom he brought with him, quite sufficient to drive the invading Frenchmen from the English domain.1

Lee, deeply mortified, and disgusted with the insolent bearing of the British General returned home with his troops.

In 1757 he was appointed, by the royal governor, a justice of the peace for the county in which he resided; and such confidence had the other magistrates in his fitness to preside at the court, that they petitioned the Governor so to date Mr. Lee's commission, that he might be legally appointed the President. About the same time he was elected a member of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, although then only twenty-five years old.2 He was too diffident to engage in the debates, and it was not until some time afterward that he displayed those powers of oratory, which distinguished him in the General Congress.3

Mr. Lee fearlessly expressed his sentiments of reprobation of the course pursued by the British Government toward the colonies, and he organized the first association in Virginia for opposing British oppression in that colony, when it came in the form of the "Stamp Act." He was the first man in Virginia, who stood publicly forth in opposition to the execution of that measure, and although by birth, education and social station, he ranked with the aristocracy, he was foremost in breaking down those distinctions between the wealthy class and the "common people," as those self-constituted patricians called those who labored with their hands. Associated with him, was the powerful Patrick Henry, whose stormy eloquence strongly contrasted with the sweet-toned and persuasive rhetoric of Lee, but when they united their power the shock was always irresistible.

Mr. Lee was one of the first "Committee of Correspondence"4 appointed in Virginia in 1778, and he was greatly aided in the acquirement of knowledge respecting the secret movements and opinions of the British Parliament, by frequent letters from his brother, Arthur Lee, who was a distinguished literary character in London, and an associate with the leading men of the realm. He furnished him with the earliest political intelligence, and it was generally so correct, that the Committees of Correspondence in other colonies always received without doubt, any information which came from the Virginia Committee. Through this secret channel of correct intelligence, Richard Henry Lee very early learned that nothing short of absolute political independence would probably arrest the progress of British oppression and misrule, in America. Hence, while other men thought timidly of independence, and regarded it merely as a possibility of the distant future, Mr. Lee looked upon it as a measure that must speedily be accomplished, and his mind and heart were prepared to propose it whenever expediency should favor the movement.

He was very active in promoting the prevalence of non-importation agreements;5 and when he heard, through his brother, of the "Boston Port Bill," he drew up a series of condemnatory resolutions to present to the Virginia Assembly.6 The Governor heard of them, and dissolved the Assembly before the resolutions could be introduced. Of course this act of royal power greatly exasperated the people, and instead of checking the ball that Mr. Lee had put in motion, it accelerated its speed. The controversy between the Governor and representatives here begun, continued, and the breach grew wider and wider, until at length, in August, 1774, a convention of delegates of the people assembled at Williamsburgh, in despite of the Governor's proclamation, and appointed Richard Henry Lee, Patrick Henry, George Washington and Peyton Randolph, to the General Congress called to meet in Philadelphia on the fifth of September, following. In that Congress, Mr. Lee was one of the prime movers, and his convincing and persuasive eloquence nerved the timid to act and speak out boldly for the rights of the colonists. His conduct there made a profound impression upon the public mind, and he stood before his countrymen as one of the brightest lights of the age.

Mr. Lee was elected a member of the House of Burgesses of Virginia as soon as he returned home from Congress, and there his influence was unbounded. He was again elected a delegate to the General Congress for the session of 1775, and the instructions and commission to General Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental army were the productions of his pen. He was placed upon the most important committees, and the second "Address" of Congress to the people of Great Britain, which created such a sensation in that country, was written by him. During a short recess in September, he was actively engaged in the Virginia Assembly where he effectually stripped the mask from the "conciliatory measures," so called, of Lord North, which were evidently arranged to deceive and divide the American people. By this annihilation of the last vestige of confidence in royalty, in the hearts of the people of Virginia, he became very obnoxious to Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of the province, and he tried many ways to silence the patriot.

Mr. Lee was a delegate in the Congress of 1776, and on the seventh day of June of that year, pursuant to the dictates of his own judgment and feelings, and in obedience to the express instructions of the Assembly of Virginia, he introduced the resolution so often referred to in these memoirs, for a total separation from the mother-country.7 The consideration of the resolution was made the special order of the day, for the first Monday in July, and a committee, of which Thomas Jefferson was chairman, was appointed to draw up a Declaration of Independence.8 This document was presented to Congress on the first day of July; and after several amendments made in committee of the whole, it was adopted on the fourth, by the unanimous votes of the thirteen United Colonies.

Mr. Lee continued an active and indefatigable member of Congress until 1779, when, as lieutenant of the county of Westmoreland, he entered the field at the head of the militia, in defence of his State. He was occasionally absent from Congress on account of his health, and once on account of being charged with toryism, because he received his rents in produce, instead of the depreciated continental currency! He demanded and obtained an investigation before the Virginia Assembly, and it resulted in the passage of a resolution of thanks for his many services in and out of Congress, and by his immediate re-election to a seat there.

Mr. Lee was again chosen a delegate to Congress in 1783, and was elected President thereof by the unanimous voice of that body. He filled the high station with ability, and at the end of the session received the thanks of that assembly. Although not a member of any legislative assembly when the Federal Constitution was submitted to the several States for action, he wielded a powerful influence, in connection with Patrick Henry and others, in opposing its ratification by Virginia, without amendments. But when it was finally adopted and became the organic law of the Union, he cheerfully united in carrying it into effect, and was chosen the first Senator from Virginia under it. He retained the office until the infirmities of age compelled him to retire from public life, and he there enjoyed, amid the quietude of domestic retirement, the fruits of a well-spent existence.

His last days were crowned with all the honor and reverence which a grateful people could bestow upon a benefactor, and when death cut his thread of life, a nation truly mourned. He sunk to his final rest on the nineteenth day of June, 1794, in the sixty-fourth year of his age.

Mr. Lee was a sincere practical Christian, a kind and affectionate husband and parent, a generous neighbor, a constant friend, and in all the relations of life, he maintained a character above reproach. "His hospitable door," says Sanderson, "was open to all; the poor and destitute frequented it for relief, and consolation ; the young for instruction; the old for happiness; while a numerous family of children, the offspring of two marriages, clustered around and clung to each other in fond affection, imbibing the wisdom of their father, while they were animated and delighted by the amiable serenity and captivating graces of his conversation. The necessities of his country occasioned frequent absence; but every return to his home was celebrated by the people as a festival; for he was their physician, their counsellor, and the arbiter of their differences. The medicines which he imported were carefully and judiciously dispensed; and the equity of his decision was never controverted by a court of law."

1 Braddock did indeed accept the services of Major Washington and a force of Virginia militia, and had he listened to the advice of the young Virginia soldier, he might not only have avoided the disastrous defeat at the Great Meadows, but saved his own life. But when Washington, who was well acquainted with the Indian mode of warfare, modestly offered his advice, the haughty Braddock said: "What, an American buskin teach a British General how to fight!" The advice was unheeded, the day was lost, and Braddock was among the slain.

2 Such confidence had the people in the judgment and integrity of Mr. Lee, even though so young, that, it is said, numbers of people on their dying beds, committed to him the guardianship of their children.

3 The first time he ever took part in a debate, sufficiently to make a set speech, was in the House of Burgesses, when it was proposed to "lay so heavy a duty on the importation of slaves, as effectually to stop that disgraceful traffic." His feelings were strongly enlisted in favor of the measure, and the speech which he made on the occasion astonished the audience, and revealed those powers of oratory which before lay concealed. His fearlessness and independence of spirit, as well as his eloquence, were soon afterward manifested when he undertook the task of calling to account Mr. Robinson, the delinquent treasurer of the colony. A large number of the members of the House of Burgesses, who belonged to the old aristocracy of Virginia, were men, who, by extravagance and dissipation, had wasted their estates, and resorted to the ruinous practice of borrowing to keep up an expensive style of living not warranted by their reduced means. Nearly all of them had borrowed money of Mr. Robinson, and he had even gone so far as to lend them treasury notes, already redeemed, which it was his duty to destroy, to secure the public against loss. He believed that their influence and number in the House of Burgesses, would screen him from punishment, supposing there were none hardy enough to array himself against them. But Mr. Lee did array himself against all that corrupt power, and in the prosecution of the delinquent treasurer, carried his point successfully.

4 To Mr. Lee is doubtless due the credit of first suggesting the system of "Committees of Correspondence," although Virginia and Massachusetts both claim the honor of publicly proposing the measure first. So far as that claim is concerned, the proposition was almost simultaneous in the Assembly of both Provinces. It was proposed in the Virginia Assembly, on the twelfth of March, 1773, by Dabney Carr, a brother-in-law of Mr. Jefferson, and a young man of brilliant talents. The plan, however, was fixed on in a caucus at the "Raleigh Tavern," and Richard Henry Lee was one of the number. But in a letter to John Dickenson, of Pennsylvania, dated July twenty-fifth, 1768, Mr. Lee proposed the system of "Corresponding Committees," as a powerful instrument in uniting the sentiments of the colonists on the great political questions constantly arising to view.

5 Long before non-importation agreements were proposed, Mr. Lee practised the measure. In order to show the people of Great Britain that America was really independent of them in matters of luxury, as well as necessity, he cultivated native grapes, and produced most excellent wine. He sent several bottles to his friends in Great Britain, "to testify his respect and gratitude for those who had shown particular kindness to Americans." He told them that it was the production of his own hills; and he ordered his merchant in London, who had before furnished his wine, not to send any more, nor any other articles on which Parliament had imposed a duty to be paid by Americans.

6 One of these resolutions proposed the calling of a General Congress, but even the warmest partisans thought this measure altogether too rash to be thought of.

7 The resolution was as follows : -"Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States ; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown ; and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."

8 The Committee consisted of Thomas Jefferson, Dr. Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston. It may be asked, why was not Mr. Lee, by common courtesy, at least, put upon that committee, and designated its chairman? The reason was, that on the very day he offered the resolution, an express arrived from Virginia, informing him of the illness of some of his family which caused him to ask leave of absence, and he immediately started for homo He was therefore absent from Congress when the committee was formed.

Text taken from "Biographical Sketches of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence" by BJ Lossing, 1848

Return to Founding Fathers Page

Revolutionary War and Beyond Home

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments