Boston Massacre

Boston Massacre Engraving by Paul Revere

Boston Massacre Engraving by Paul RevereThe Boston Massacre was the culmination of a year and a half of tension and strife between the citizens of Boston and British troops who were stationed there in the fall of 1768 to help enforce the Townshend Acts and protect tax and customs employees from harassment.

On the evening of March 5, 1770, several days of tension came to a head when British soldiers roved around the town harassing citizens, ending up in a confrontation in front of the Custom House that left five citizens dead and six more wounded when British soldiers opened fire on a crowd of stick wielding, snowball throwing, epithet yelling citizens.

Most Americans have heard of the Boston Massacre, but you may not know the details of the event, especially the fact that gangs of British soldiers were roving around the town looking for trouble that evening. Learn more about the details of the Boston Massacre and the events that led to it below.

Boston Massacre - March 5, 1770

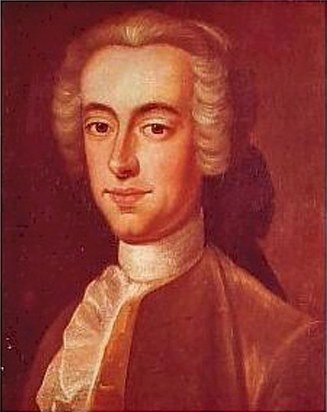

Charles Townshend

Charles TownshendThe Townshend Acts were passed by the British Parliament in the summer of 1767. The colonies had been relatively calm since the Stamp Act was repealed in March of 1766. Prime Minister William Pitt ascended to the highest position in the British government shortly afterwards, but due to frequent illness and absence, Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer, became the de facto ruler.

Lord Townshend pursued a much more aggressive stance toward the colonies than Pitt and passed a series of taxes and regulations named for him, known as the Townshend Acts. The Townshend Acts increased taxes to import lead, paper, glass, painters' colors and tea into the colonies from Britain. They also created a new board of customs commissioners for the colonies, to be headquartered in Boston. The duty of this board was to strictly enforce tax collecting and to punish smugglers.

The Townshend Acts reduced taxes on the East India Company to import tea into Britain in order to lower the cost when it was exported to the colonies. The East India Company was on the verge of collapse and Parliament hoped to boost the company's bottom line by allowing them to sell tea more cheaply to the colonists than the smuggled Dutch tea they had been purchasing in abundance.

The Townshend Acts also gave more power to vice-admiralty courts, courts that handled smuggling and tax evasion cases without the use of trials by jury. This was an offense to the colonists who believed this denied them an important right belonging to all British citizens.

Finally the Townshend Acts shut down the New York Assembly for not complying with the Quartering Act of 1765, which required the colonists to pay for and provide housing and supplies for British soldiers stationed there. If Parliament had the ability to shut down their elected assemblies, the colonists reasoned, they could do anything to them.

Learn more about the Townshend Acts here.

British soldiers occupy Boston

The effect of the Townshend Acts was to spread rioting and protesting all over the colonies. In Boston, where the opposition was particularly intense, citizens harassed government and customs officials to the point that it was hard for them to do their jobs. Officials requested military assistance and protection from Parliament, which was granted by Wills Hill, the Colonial Secretary, a position created to deal with the growing tensions in the colonies.

On October 1, 1768, the 14th and 29th Regiments of the British army arrived, making a showy display when they disembarked from their ships and marched through town. The 64th and 65th Regiments arrived two weeks later. In all, 4,000 soldiers were stationed in Boston, a clear signal of how out of control the town was, since the population was only between 15,000 and 20,000 people! That's one soldier for every 3 or 4 people!

A View of Part of the Town of Boston by Paul Revere Shows the arrival of British troops in Boston, 14 ships with troops gathering on Long Wharf and marching into town

A View of Part of the Town of Boston by Paul Revere Shows the arrival of British troops in Boston, 14 ships with troops gathering on Long Wharf and marching into townSoldiers were housed in public places and on Boston Common. They were often placed as sentries and were often seen around town. Townspeople rightly viewed their city as "occupied" by a foreign army and frequently harassed the soldiers, calling them epithets such as "lobsterback" for their red coats, telling them to go back to Britain and accusing them of mistreating people.

The effect of this treatment on the soldiers cannot be overestimated. The soldiers were young, underpaid, lived in horrid conditions (many in tents) where it was easy to catch diseases, were often mistreated by harsh officers and were far away from home and family. They were continually subjected to harsh treatment by the townspeople, to the point where they often had things thrown at them and were spat upon as they served. Many soldiers deserted the army due to the foul treatment.

Over time, tensions between soldiers and citizens grew so bad that many people anticipated an outbreak of violence that would leave many people dead. There would be eighteen months of building tensions before their culmination at the Boston Massacre.

Since no major incidents occurred since the troops arrival, the 64th and 65th Regiments were removed from Boston in July of 1769, leaving only the 14th and 29th Regiments to defend the Customs officials. General Thomas Gage, the Commander of the British Armed Forces in North America, would have even removed the last two regiments if not for the objections of Governor Francis Bernard who feared what would happen to officials if the troops were removed. Gage feared what would happen if the troops remained.

Though tensions were constant, they began to pick up in July, 1769. Blows were exchanged between Private John Riley and a Boston merchant named Jonathan Winship when Riley tried to rescue a boy who was being beaten by another citizen. Riley ended up being charged with assault and was ordered to pay a fine, which he did not do. When the Justice of the Peace ordered Riley to jail for not paying the fine, several men from his regiment physically rescued him from the jail and fought off the constable in the process.

The Death of Christopher Seider The crowd stands in front of the "Lillie Grocer." The sign reads, "Lillie sells taxed tea." Artistic license has the boy shot in front of the store with Richardson holding a gun in the second floor window. In reality, Christopher was shot at Richardson's home nearby.

The Death of Christopher Seider The crowd stands in front of the "Lillie Grocer." The sign reads, "Lillie sells taxed tea." Artistic license has the boy shot in front of the store with Richardson holding a gun in the second floor window. In reality, Christopher was shot at Richardson's home nearby.In October of that year, British Ensign John Ness got into a confrontation with Robert Pierpoint and was charged with assault and stealing the man's wood. As he went to the authorities to face the charges, Ness and some fellow soldiers were attacked by a crowd of citizens in which several of the soldiers were badly hurt.

On February 22, 1770, protestors were gathered in front of the shop of Theophilus Lillie, a Loyalist merchant who was accused of importing British goods against the organized boycott. A customs official named Ebenezer Richardson attempted to tear down a sign accusing Lillie of breaking the boycott and to break up the protest.

Richardson was chased to his home by the crowd which began pelting it with rocks, one of which hit Richardson's wife in the head. An angry Richardson shot his gun into the crowd and hit an eleven year old boy named Christopher Seider who died. Seider's funeral was a flashpoint as nearly 2,000 outraged citizens attended it a few days later.

Ebenezer Richardson was tried and found guilty of murder, but received a royal pardon for doing it in self-defense. This only angered the townspeople and fueled the flames even more.

The Boston Massacre would occur only eleven days later.

A typical ropewalk, this one at the Historic Dockyard at Chatham, England

A typical ropewalk, this one at the Historic Dockyard at Chatham, EnglandThree days before the Boston Massacre

The working class was hit particularly hard due to the most recent belligerence between the colonists and their homeland. Boycotts reduced factory, shopkeeping and shipping jobs. American sailors were often impressed into service on British warships. Soldiers stationed in the colonies were paid poorly and would often try to supplement their meager incomes by getting odd jobs during their off hours - taking much needed jobs that would have gone to colonists.

Low wage jobs could be found in factories or on the docks. One job in particular that existed in abundance was making rope for sailing ships. A typical ship could have as much as 20 miles of rope.

Ropes were made in "ropewalks," which were extremely long "walks," often covered or completely enclosed, where workers would walk backwards twisting strands of yarn together into various weights of rope. A standard rope of the day would have been from 700 to 1000 feet long and ropewalks could be up to a quarter mile in length. It was a conflict between a soldier and a ropewalk employee that ignited the event that we know as the Boston Massacre.

On March 2nd, 1770, Private Patrick Walker went to the ropewalk of John Gray around noon, apparently looking for work. An employee by the name of William Green asked him, seeming to help, if he was looking for work, to which Patrick Walker replied that he was. Green then told Walker, "I have a job for you. You can clean my ****house!" (a very slang word for an outhouse!) Of course, this insult got a huge laugh from the other ropeworkers.

From the deposition of John Gray,

"Col. Dalrymple, to whom I related what I understood had passed at the ropewalk days before... replied it was much the same as he had heard from his people; but says he, 'your man was the aggressor in affronting one of my people, by asking him if he wanted to work, and then telling him to clean his little-house [outhouse].' For this expression I dismissed my journeyman on the Monday morning following; and further said, I would do all in my power to prevent my people's giving them any affront in future. He then assured me, he had and should do everything in his power to keep his soldiers in order."

After the insult, Walker and Green got into a scuffle over the matter and Green was supported by his co-workers causing Walker to flee. Private Walker came back shortly with 8 or 9 other soldiers and the fight continued.

In the deposition from Jeffrey Richardson,

"I, Jeffrey Richardson, of lawful age, testify and say, that on Friday, the second instant, about 11 o'clock, A.M., eight or ten soldiers of the 29th regiment, armed with clubs, came to Mr. John Gray's ropewalks, and challenged all the ropemakers to come out and fight them. All the hands then present to the number of 13 or 14 , turn'd out with their wouldring sticks, and beat them off directly. They very speedily returned to the ropewalk, reinforced to the number of thirty or forty, and headed by a tall negro drummer, again challenged them out, which the same hands accepting, again beat them off with considerable bruises."

The ropemakers got the better of the soldiers, who fled for help. This time, the soldiers came back with 30 or 40 soldiers and the fight ensued again! But again, the tough, muscled factory workers fought the soldiers off who went back to their barracks to nurse their wounds.

This event and the events of the next few days, right up to the event in front of the Custom House known as the Boston Massacre, have inexplicably been left out of many accounts of the Boston Massacre. Understanding the fight that broke out at the ropewalks, the response of the soldiers over the next few days and the response of the working class laborers and seamen is, however, key to understanding why the Boston Massacre took place.

These events have probably been left out of most histories simply for brevity's sake, so get ready to hear some things you've never heard before!

Effects of the ropewalk incident

The fight at the ropewalks happened on Friday, March 2nd, 1770. Over the next two days, reports began to be heard of working class citizens trying to pick fights with soldiers around the town, possibly encouraged by the Sons of Liberty to provoke an incident. Factory workers, low-wage apprentices, sailors and the like were already angry with soldiers for occupying their city, treating citizens with disdain, taking their jobs and for the recent death of the Seider boy, but news of the fight at the ropewalks quickly spread through the docks, factories and shops of Boston and was like kindling to a flame for the simmering tensions.

In addition to citizens looking for a fight, the bruised and embarrassed soldiers and their comrades had finally come to the breaking point as well. Soldiers were under strict orders not to use any force against the colonists unless under direct orders from a city magistrate. They could not defend themselves and suffered frequent abuse consisting of everything from name-calling to having their equipment (which they had to pay for themselves) stolen to being pelted with rocks and garbage. The embarrassment of being badly beaten at the ropewalks added insult to injury and many soldiers decided it was time to retaliate and take revenge.

It was not uncommon during the British occupation of Boston to hear soldiers make derogatory comments about the colonists, accusing them of being disloyal to Britain, being brutish, unsophisticated and the like. It was also not uncommon to hear them make threats amongst themselves along the lines of, "If I ever get the chance, I'll kill as many of these colonists as I can."

For example, from the deposition of Samuel Hemmingway, referring to Sergeant Matthew Kilroy, who was one of the soldiers accused in the Boston Massacre:

Question: Did you ever hear Kilroy make use of any threatening expressions, against the inhabitants of this town?

Answer: Yes, one evening I heard him say, he would never miss an

opportunity, when he had one, to fire on the inhabitants, and that he

had wanted to have an opportunity ever since he landed."

And another from the deposition of John Wilme:

"I, John Wilme, of lawful age, testify that about ten days before the late massacre, Christopher Rumbly of the 14th regiment, was at my house... [and]... did talk very much against the town, and said if there should be any interruption, that the grenadier's company was to march up King street... and that he had been in many a battle; and that he did not know but he might be soon in one here; and that if he was, he would level his piece so as not to miss; and said that the blood would soon run in the streets of Boston."

When the bruised and battered soldiers from the ropewalks incident on the 2nd returned to their barracks and other soldiers learned what happened, a plot was hatched to take revenge on the rebellious city and do what their superiors had failed to do... show them who was in charge.

Plans were made to randomly attack as many citizens as they could on the following Monday, March 5th. Rumors began to circulate that there would be danger to anyone on the streets that evening. Some soldiers, hearing of the plans, went to local citizens they had befriended and warned them not to leave their homes on the evening of March 5th. If you read the depositions from witnesses to the events of March 5th, you will find countless instances of people becoming aware of the soldiers' plans for Monday night.

For example,

- "MATTHEW ADAMS (living with Mr. John Arnold) being of lawful age, testifies and says, that on Monday evening the fifth day of March instant, between the hours of seven and eight of the clock, he went to the house of corporal Pershel, of the twenty ninth regiment, near Quaker-lane, where he saw the corporal and his wife, with one of the fifers of said regiment; when he had got what he went for, and was coming away, the corporal called him back, and desired him with great earnestness to go home to his master's house as soon as business was over, and not be abroad on any account that night in particular, for the soldiers were determined to be revenged on the ropewalk people; and that much mischief would be done; upon which the fifer (about eighteen or nineteen years of age) said he hoped in God they would burn the town down; on this he left the house, and the said corporal called after him again, and begg'd he would mind what he said to him, and further saith not."

- "WILLIAM NEWHALL, living in fifth-street, of lawful age, testifies and says, that on Thursday night, being the first of March instant, between the market and Justice Quincey's, he met four Soldiers of the 29th regiment, all un-arm'd, and that he heard them say, there was a great many that would eat their dinners on Monday next, that should not eat any on tuesday. (This testimony indicates the plan may have been in the works even before March 2nd.)

- "JOHN FISHER, of lawful age, testifies and saith, that on the second day of March, between eleven and twelve o'clock, A. M. he saw about six soldiers going towards Mr. John Gray's rope-walk, some with clubs ; they had not been there long, before they returned quicker than they went and retreated into their barracks, and bro't out the light infantry company, with many others, and went against the rope makers again; but were soon beat off as far as Green's-lane, the soldiers following and chasing many persons they could see in the lane with their clubs, and endeavoring to strike them, when a corporal came and ordered them into the barracks. -- And further saith that on Saturday the third instant, he saw the soldiers making clubs; and by what he could understand from their conversation, they were determined to have satisfaction by Monday."

- "MARY THAYER of lawful age testifies and says, that on Sabbath day evening, the 4th current, a soldier of the 29th named Charles Malone, came into Mr. Amos Thayer's house, brother to the deponent, and sent a young lad belonging to Mr. Thayer up stairs to his master, desiring him to come down to him. Mr. Thayer refused to come down or have any thing to say to him. The deponent going down on other occasion, said she would hear what the soldier had to say. And coming to the soldier told him her brother was engaged. The soldier said, your brother as you call him is a man I have a very great regard for, and came here to desire him to keep in the house and not be out, for there would be a great deal of disturbance and blood between that time and Tuesday night at 12 o'clock. He repeatedly said he had a greater regard for Mr. Thayer than any one in Boston, and on that account came to desire him to keep in the house, which if he did there would be no danger. After repeating the above frequently, he even turned at the door, and said my name is Charles Malone, your brother knows me well, and insisted very earnestly that the deponent would not neglect informing her brother, and further saith not."

- "NATHANIEL NOYES of lawful age testifies and says, that on last Sabbath evening, the 4th day of March current, a little after dark, he saw five or six soldiers of the 14th and 29th regiments, each of them with clubs, passing thro' Fore-Street, and heard them say, that if they saw any of the inhabitants of this town out in the street after nine o'clock, they swore by God, they would knock them down, be they who they will."

Monday, March 5, 1770

On the evening of March 5th, the depositions show that soldiers started roaming around the city, apparently attacking anyone they came across, starting around 7 or 8 in the evening. There are countless reports of citizens walking home from a neighbor's house and running into bands of soldiers who accosted them, beating them with cudgels, hitting them with their rifle butts, even slashing at them with their swords.

For example,

- "WILLIAM LEWIS testifies and says, that on the evening following Monday the fifth instant, about nine o'clock, he passing through Kingstreet in order to go into Cornhill street, while he was crossing Kingstreet heard some people wrangling at the Custom-house door, and he immediately see four soldiers of the 29th regiment jump out from between the Watch-house and the Town-House steps, at the east end of the house, in their short jackets with drawn swords in their hands, two of whom run after the deponent and pursued him close until he got to his home in Cornhill street, where just as he entered the door one of the soldiers struck at him either with his sword or bayonet, but the deponent rather thinks it was the latter, as he afterwards found a three square hole cut in the skirt of his surtout, which he verily believes was made by the blow that the soldier struck at him."

- "HENRY BASS of lawful age testifies and says, that going from his house in Winter-street, on Monday evening the fifth of March, to see a friend in the neighbourhood of the Rev. Dr. Cooper's meeting-house; that the bell was ringing for nine o'clock when he came out of his house, and that he proceeded down the main-street, and going near Draper's alley, leading to Murray's barracks, thro' which he purposed to pass, heard some boys huzzaing, and imagines that there were six or seven of them and not more; and presently after he saw two or three persons in said alley with weapons, but cannot positively say what they were. - Soon after several more came into the alley and made a sally out, and those that came out were soldiers, and thinks were all grenadiers, as they were stout men, and were armed with large naked cutlasses; they made at every body coming in their way, cutting and slashing; the said deponent very narrowly escaped receiving a cut from the foremost of them, who pursued him below Mr. Simpson's stone shop, where he made a stand; presently after, going up Cornhill he met an oyster man, who said to the deponent, damn it, this is what I got by going up, and shewed the deponent a large cut he had received from one of the soldiers with a cutlass over his right shoulder; said deponent thinking it not safe but very dangerous for him to go through the alley, he returned home by the way of the Kingstreet through Royal Exchange lane."

- "I NATHANIEL APPLETON, of lawful age, testify, that on Monday evening the 5th instant, between nine and ten o'clock, I was sitting in my house in Cornhill, heard a noise in the street, I went to my front door and saw several persons passing up and down the street, I asked what was the matter? was informed that the soldiers at Murray's barrack were quarrelling with the inhabitants. Standing there a few minutes, I saw a number of soldiers, about 12 or 15, as near as I could judge, come down from the southward, running towards the said barrack with drawn cutlasses, and appeared to be passing by, but on seeing me in company with Deacon Marsh at my door, they turned out of their course and rushed upon us with uplifted weapons, without our speaking or doing the least thing to provoke them, with the utmost difficulty we escaped a stroke by retreating and closing the door upon them. I further declare, that at that time my son, a lad about 12 years old, was abroad on an errand, and soon came home and told me that he was met by a number of soldiers with cutlasses in their hands, one of which attempting to strike him, the child begg'd for his life, saying, pray soldier save my life, on which the soldier reply'd, No damn you, I will kill you all, and smote him with his cutlass, which glanced down along his arm and knocked him to the ground where they left him, after the soldiers had all passed, the child arose and came home, having happily received no other damage than a bruise on the arm - I further declare that the above related transactions happened but a few minutes before the soldiers fired upon the people in Kingstreet."

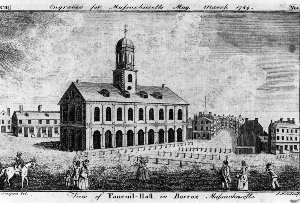

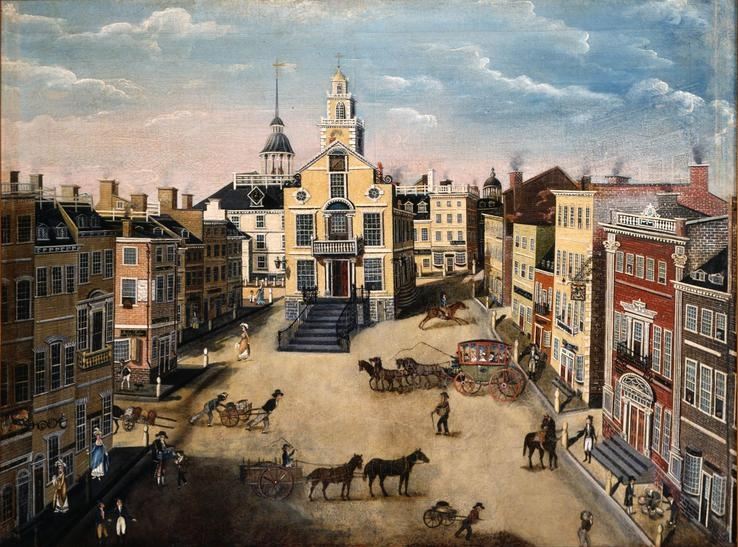

Faneuil Hall and Dock Square as they appeared in 1789

Faneuil Hall and Dock Square as they appeared in 1789Once the soldiers started their rampage, it wasn't long before citizens started responding. Several citizens challenged soldiers in the street, imploring them to stop attacking innocent people. A group of several hundred citizens gathered at Dock Square in front of Faneuil Hall where they were encouraged by the fiery rhetoric of a "tall man in a white wig and a red coat," who has never been identified. He encouraged them to take up weapons to defend themselves.

Some of this crowd marched toward the Main Army barracks on King Street near the Town House (now called the Old State House) a few blocks away. The rest of them marched on the army barracks known as Murray's Barracks, which was in Boylston's Alley just off Dock Square and demanded that the officers herd the soldiers back into the barracks and get control of their men.

This barracks lay in a narrow alley and the gate of the barracks was protected by soldiers bearing clubs, bayonets and shovels. A band of outraged soldiers chased some of the crowd through the alley. A barrage of snowballs and insults were hurled at soldiers behind the gates. Captain John Goldfinch and other officers urged the junior officers to hurry the soldiers into the barracks before a riot ensued. A local innkeeper, Richard Palmes, demanded that the officers keep the soldiers in their barracks and was able to persuade the crowd to disperse.

Richard Palmes character played by actor John Bedford Lloyd at the Boston Massacre Trials in the HBO movie John Adams

Richard Palmes character played by actor John Bedford Lloyd at the Boston Massacre Trials in the HBO movie John AdamsIf you read through the long list of depositions, you will see numerous encounters between soldiers and citizens breaking out all over the city that night. Some of the officers tried to get the soldiers back into the barracks. Other officers encouraged them. Bands of soldiers were seen countless times running up and down the streets with weapons drawn, attacking people in their own doorways and knocking people to the ground. Citizens began to organize and fight back, which stirred up the soldiers, anxious for revenge, even more.

Once it became apparent that a serious fight was about to occur, someone in the fray got the bright idea to start ringing the town's church bells, the traditional means of awakening the town to put out a fire, in order to arouse the people and inform them of what was taking place in the streets so they could defend themselves. As the bells rang, more and more colonists began to pour into the streets, buckets in hand and pushing fire engines, looking for the fire that needed to be quenched.

Edward Garrick at the Custom House

After an hour or two of marauding soldiers beating citizens in the street, the citizens began to organize and pour into the streets. Things were getting to the boiling point. Crowds of citizens were gathering to defend themselves and confront the soldiers. At this point, a simple comment made in front of the Custom House ended up being the flashpoint that turned the evening's events into a bloodbath and one of the most famous events leading to the American Revolution... what we today call the Boston Massacre.

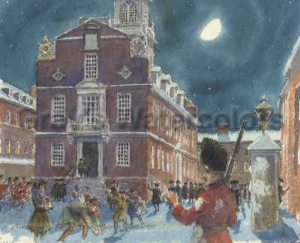

The Town House, now known as the Old State House The Old State House as it looks today. It is the oldest public building in Boston. The Boston Massacre took place about a block in front of the Town House in front of the Custom House.

The Town House, now known as the Old State House The Old State House as it looks today. It is the oldest public building in Boston. The Boston Massacre took place about a block in front of the Town House in front of the Custom House.Around 9 that evening, two young boys named Edward Garrick and Bartholomew Broaders were walking in front of the Custom House on King Street where taxes were collected, just down the street from the Town House (now called the Old State House) where the Massachusetts legislature met. Garrick was an apprentice to barber and wigmaker John Piemont and he threw an insult at a passing soldier named Captain John Goldfinch. Goldfinch had just come from the Boylston's Alley barracks after trying to calm the violence there and was now on his way back to his own barracks, the Main Army barracks, on King Street.

Garrick brashly accused Goldfinch of not paying money he owed to his master, Mr. Piemont, for a haircut. Garrick is said to have called out, "There goes the fellow who hath not paid my master for dressing his hair." In reality, Goldfinch had paid the bill the day before, but Garrick was unaware of it. Goldfinch ignored Garrick and continued on down the street.

Garrick, however, persisted, and continued telling several people in the street that Goldfinch owed his master money. Private Hugh White was posted in the sentry box outside of the Custom House, where the King's money was stored, for sentry duty. White overheard the conversation between Garrick and Goldfinch and observed Garrick's continued disparagement of a fellow soldier. White defended Captain Goldfinch to the boys, allegedly saying that, "He is a gentleman, and if he owes you anything he will pay for it."

At this point, Garrick got mouthy with Private White and told him, "There were no gentlemen left in the regiment." White started to lose his temper, left his post and approached the boys. They exchanged several heated words and insults which angered Private White to the point that he smacked Garrick in the face with the butt of his rifle, knocking him down.

Bartholomew Broaders, Garrick's friend, began to yell and scream that Private White had attacked his friend. There were already so many people out by this time that it didn't take long for a crowd to gather to confront Private White. After hearing what happened to Garrick, a large group of protesters came from the Main Army barracks which was only a few hundred feet away, where they had been demanding the officers to take control of their soldiers. The large crowd marching from Dock Square also appeared in King Street about this same time. The crowd swelled to several hundred people quickly.

1770 - Harassment Before Massacre Depicting Private Hugh White being harassed at the at the Custom House shortly before the Boston Massacre Buy from Gray's Watercolors

1770 - Harassment Before Massacre Depicting Private Hugh White being harassed at the at the Custom House shortly before the Boston Massacre Buy from Gray's WatercolorsPrivate White instantly knew that he was in danger. He loaded his weapon and leveled it that the crowd, warning that he would shoot if he had to. The crowd began pelting White with sticks, coal, oyster shells, snowballs (it was winter and there was a foot of snow on the ground) and anything else they could find. White backed up onto the Custom House steps, threatened the crowd again that he would shoot and began to call for help. A 19 year old Henry Knox, who would one day become a general in the Revolutionary War and one of George Washington's most trusted associates, entered the scene and warned Private White that "if he fired he must die for it."

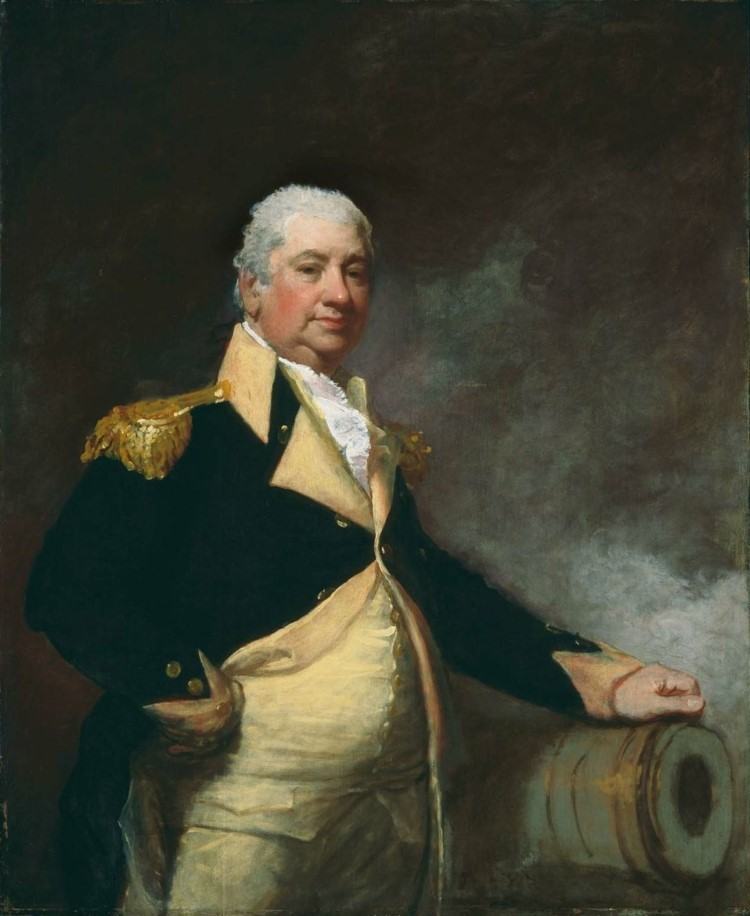

Captain Thomas Preston

Captain Thomas PrestonAt some point, messengers sent from Private White got to Captain Thomas Preston, who was the Officer of the Day at the nearby Main Army barracks of the 29th Regiment. The word he received was that Private White was in danger and blood was going to be spilt at the Custom House if something wasn't done right away. The Officer of the Day was a rotating position in charge of security and law enforcement at his post. Preston hesitated for some time, knowing that White was in danger, but also hesitant to put more soldiers into the streets with such a large mob threatening revenge.

Captain Preston eventually ordered seven men to join him. He came running with two columns of men, a non-commissioned officer named Corporal William Wemms and six privates, John Carroll, William McCauley, Matthew Kilroy, William Warren and Hugh Montgomery. Eyewitness accounts say the soldiers came running with their bayonets drawn, pushing through the crowd to get to White. At this point, the soldiers' bayonets were drawn, but their guns were not loaded.

Accounts vary, but there may have been anywhere from 300 to 400 people in the crowd by this time. Many began to disperse, however, when they saw the soldiers arrive. Several people, including the young Henry Knox, again trying to calm the situation, spoke to Preston when he arrived and warned him that it was illegal for soldiers to fire on civilians and that there would be a price to pay if they did so. Preston responded that he he was aware of the risk.

At first, Captain Preston ordered Private White to join his men and tried to march them back to the barracks, but the crowd was blocking them and began to press in. Preston warned the crowd that they should back off and disperse, but they began throwing ice, coal and anything else they could find at the soldiers. Preston then had the soldiers back up against the Custom House and form into a semi-circular stance for protection. He stood in front of them and ordered them to load their weapons.

The mob taunted the soldiers, yelling insults such as "Bloody lobsterback!" (for their red uniforms), "Kill 'em!" and "Fire, cowards!" The crowd smacked their muskets with clubs and sticks and dared them to fire, secure in the knowledge that the soldiers could not legally fire their weapons within the city without the permission of a civil magistrate.

The first shots of the Boston MassacreAccounts differ at this point about who fired the first shot and what caused the first shot to be fired. As you know, when you have a large group of people telling what they saw at any given event, there will be numerous variations in what they saw. Some people saw it from a different angle or distance. Some saw the beginning, but not the end. Some people interpret what they see differently.

According to the depositions of witnesses to the Boston Massacre, some people saw a large club hit Private Hugh Montgomery and knock him off balance on the ice. Montgomery panicked and when he arose, he fired his weapon, either because someone yelled, "Fire!," or because he was simply acting in self-defense.

Other accounts say Crispus Attucks, a mulatto runaway slave who was now a sailor, took the lead by striking Captain Preston with a "large cord-wood stick" and shouting, "Let us strike at the root; let us fall on the nest! The Main Guard, the Main Guard!" Montgomery's bayonet was struck by the club as it glanced off Preston's shoulder causing him to fall on the ice, while Attucks attempted to get the rifle from him.

As Montgomery wrestled with Attucks to get his gun back, someone from behind them cried, "Fire! Why don't you fire??!!" It has never been determined who that person was, but it may have been Montgomery himself, pleading with his fellow soldiers to protect him. When Montgomery arose, he fired the first shot, hitting Attucks in the chest. Again, whether at the direction of someone yelling, "Fire!," or because he was acting in self-defense, has never been definitively determined.

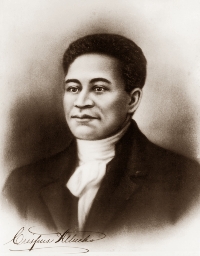

Crispus Attucks

Crispus AttucksCrispus Attucks died on the spot and is sometimes considered to be the first casualty of the Revolutionary War. Since he was a former slave and a mulatto (part black and part Native American Indian), he is often celebrated as an African-American hero for his place in the protesting and for his sacrifice. In the trial of the soldiers later, Attucks would be painted negatively and as an aggressor by the soldiers' attorney John Adams, but his second cousin Samuel Adams would defend Attucks, saying he "had as good a right to carry a stick, even a bludgeon, as the soldier who shot him had to be armed with musket and ball."

Other witnesses put the sequence of events like this: Richard Palmes, just arrived from Boylston's Alley, was also in the middle of the scene. Palmes approached Preston, with a club in hand for defense, put his hand on his shoulder and asked him if the soldiers' weapons were loaded. Preston said they were, but he would not order them to fire because he was standing in front of them and would be asking them to shoot himself. Crispus Attucks stood nearby.

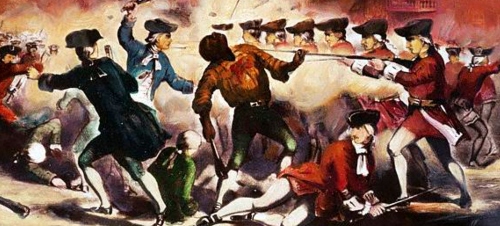

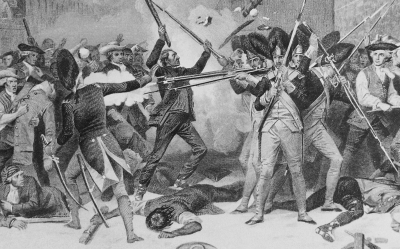

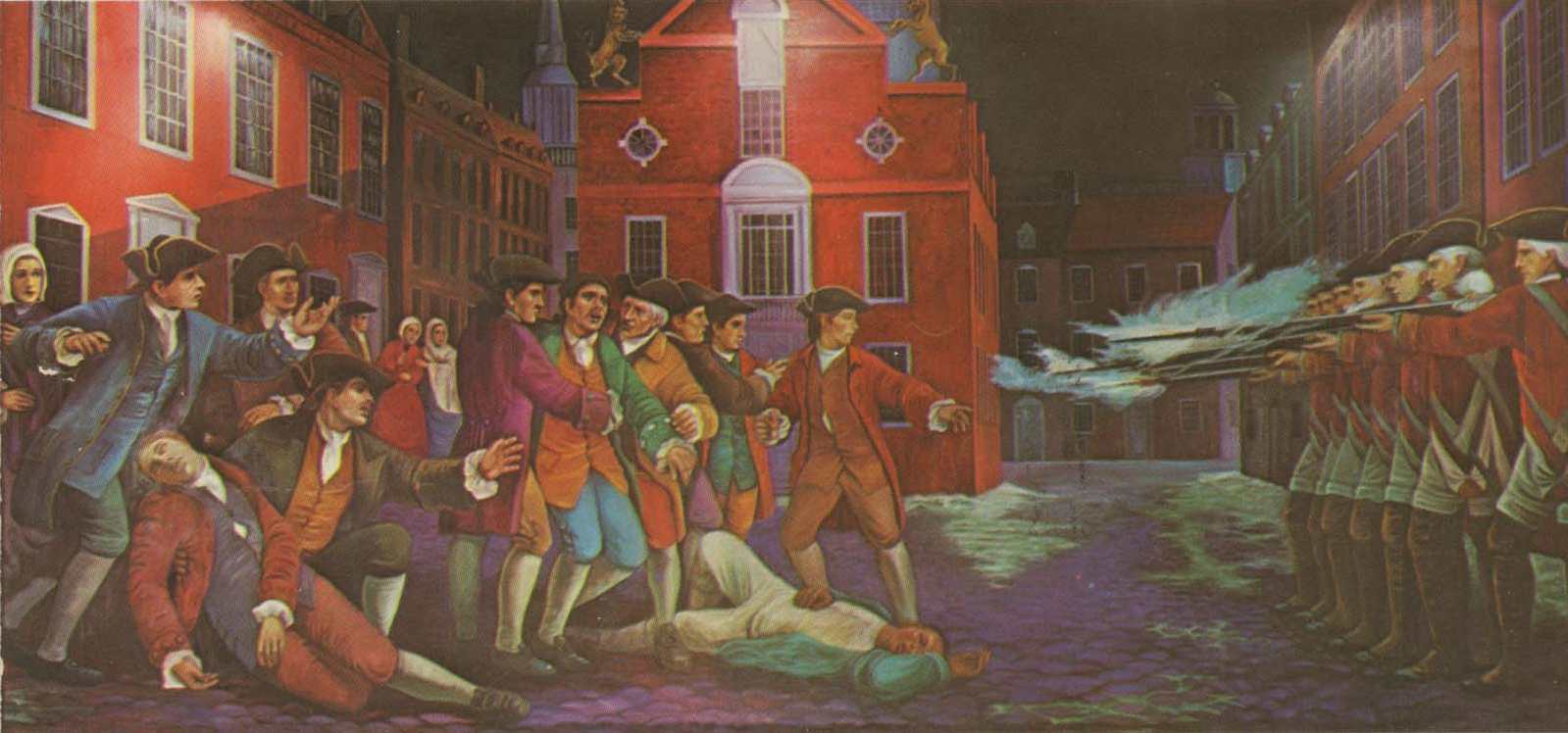

In this depiction, Captain Preston, at the left, tries to stop the soldiers from firing

In this depiction, Captain Preston, at the left, tries to stop the soldiers from firingAt this point a club flew through the air and hit Private Montgomery who fell on the ice. Attucks, who was agitated already, tried to grab Montgomery's gun, which Montgomery fired after wrestling control of the gun back. Another soldier fired on Attucks as well and he was hit twice in the chest. Either Montgomery yelled to the other soldiers to "Fire!" or Captain Preston yelled to the men "Don't fire!," which only caused the other soldiers to fire in the confusion. At this point, an outraged Richard Palmes struck Montgomery on the arm to get him to stop, then struck at Preston, narrowly missing his head and striking him in the arm as well, all in an effort to get the soldiers to stop firing.

Dozens of witnesses were interviewed. Some of their recollections matched, while others didn't. You can see how there are various elements of the story that are the same through each testimony, but the facts vary slightly. At the least, the stories all agree that something or someone hit Private Montgomery, he was alarmed for his own safety and fired the first shot.

After the first shot was fired by Private Montgomery, several of the other soldiers fired immediately. Some colonists began to scatter as the shots rang out. Attucks was struck twice in the chest and died on the spot, as did Samuel Gray, a ropeworker at Gray's ropeworks, who died from a shot to the head "as big as a man's hand" as he urged the soldiers not to fire.

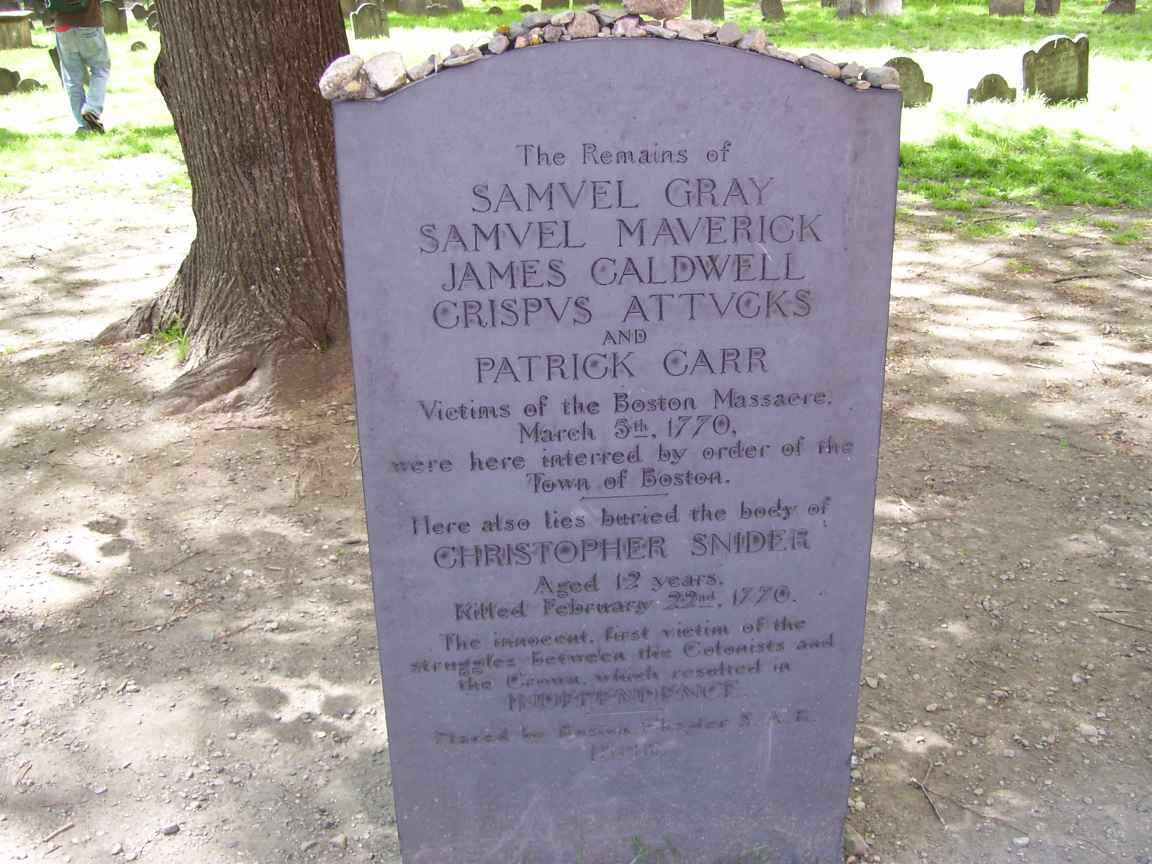

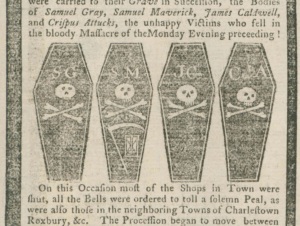

Boston Massacre Victims

Boston Massacre VictimsJames Caldwell, a sailor who had no family in Boston, was running from the scene across the street when he was hit. He died in the street from two gunshot wounds to the back.

The soldiers quickly reloaded and another round of bullets shot through the crowd. Patrick Carr, a 30 year old Irish immigrant and leather worker was shot in the hip by a shot that "tore away part of the backbone," while he was simply crossing the street with his friend Charles Connor. Carr had come out in response to the fire call with his friend. Carr may have understood there was trouble brewing with the soldiers because he grabbed his cutlass as he went out the door, but Connor had persuaded him to leave it behind. He died two weeks later from his wounds.

Samuel Maverick, a 17 year old boy, died from a shot through the chest and belly that ricocheted off a wall as he ran away from the scene. Maverick was an apprentice ivory turner, meaning he made personal items such as umbrella handles, walking cane heads and the like from ivory. Maverick had come out with his friends in response to the churchbells, thinking there was a fire to put out. He did however, dare the soldiers to fire as the soldiers pointed their guns at the crowd and was seen shouting, "Murder!" after the first shots were fired. Samuel made it to his mother's house, but died the following morning.

Tailor John Green and apprentice David Parker were shot in the legs, Robert Patterson was shot in the arm and apprentices Christopher Monk and John Clark were injured as well. Merchant Edward Payne was shot in the arm as he stood on the porch of his store on King Street. All of these victims, however, survived.

Captain Preston frantically tried to stop the soldiers from firing again, rushing around and knocking their guns upwards away from the crowd. In the end, three colonists were killed on the spot and two more died of their wounds. Six others were wounded, but survived.

Immediately after the Boston MassacreAfter the soldiers arrived and by the time the shots were fired, much of the crowd had already dispersed, sensing that an outbreak of violence was about to occur. Most accounts place around 50 to 80 still in the crowd when the shots were fired, but these 50 to 80 were severely tormenting the soldiers at the Custom House, who believed they were in enough danger that firing on the crowd was necessary to save their own lives.

The Custom House can be seen in the background of Paul Revere's Boston Massacre engraving.

The Custom House can be seen in the background of Paul Revere's Boston Massacre engraving.After the shots were fired, the dead and wounded were carried off. The crowd, however, began to swell as outraged citizens came out of their homes to challenge the soldiers. It was against the law for soldiers to fire on anyone in town without the permission of a civil magistrate. Not only was it against the law, but it was morally unconscionable to the colonists that soldiers would fire upon their fellow British citizens, who were unarmed and merely walking down the street.

Captain Preston retreated with his men to the Main Army barracks nearby. After being informed that a crowd of 4000 to 5000 colonists had formed and that his life was probably at stake, Preston ordered his drummers to beat the "to arms" signal, calling up the rest of the 29th Regiment.

Preston also sent word to Lieutenant Colonel William Dalrymple, the commander of the 14th Regiment and informed him of what was happening. As Dalrymple's men went to join Preston's, several officers were attacked by colonists and one was severely wounded. This brought the entire contingent of soldiers in Boston pouring into King Street who then lined up in formation in front of the Town House a few blocks away with guns loaded and aimed, ready for more violence.

Thomas Hutchinson

Thomas HutchinsonThe two sides were in a face to face standoff in the streets. It was truly a dangerous turn that could easily have escalated into an all out war on the streets of Boston, with what was now thousands of Bostonians facing down hundreds and hundreds of trained and armed soldiers who were ready to fight and take revenge for all the abuse they had suffered over the last months.

Thomas Hutchinson, who was then the Lieutenant Governor, but in Governor Francis Bernard's absence to England, was now the Acting Governor, came out after being informed of the tragedy and immediately found Captain Preston, demanding to know why he had fired on civilians. An irritated Preston informed him that the soldiers would have been killed if he had not acted.

Hutchinson, Lt. Col. Dalrymple and other civilian leaders were fortunately able to meet quickly in the Town House and bring things back from the brink. The soldiers were ordered back to their barracks. Hutchinson ordered Preston and the other soldiers involved in the bloodshed to be taken into custody and assured the crowd from the Town House balcony that justice would be served and the soldiers would be tried for their deeds. He assured them, "Let the law have its course. I will live and die by the law." This caused the tension to die down and the crowd, not wanting to see any further bloodshed, made their way back to their homes and March 5, 1770 came to a close.

Just after midnight, Justices Richard Danie and John Tudor issued a warrant for Captain Preston's arrest. He was brought to the Town House and interrogated by the judges. Around 3 am, the judges announced they had sufficient evidence to convict Preston and sent him to jail.

Aftermath of the Boston MassacreCaptain Preston and the other eight soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre were in custody by the following morning. The Boston Town Meeting, chaired by John Hancock, met the following day and appointed a committee, headed by Samuel Adams, to petition Hutchinson for the immediate removal of all British troops from the city.

Samuel Adams Demanding British Army Withdrawal after the Boston Massacre, c.1770 by Howard Pyle

Samuel Adams Demanding British Army Withdrawal after the Boston Massacre, c.1770 by Howard PyleHancock, Adams and other representatives from the Town Meeting delivered the petition to Lt. Gov. Hutchinson. At first, the Governor's Council only agreed to remove the 29th Regiment from the city, but wanted to leave the 14th for the sake of being able to adequately police the city.

When the Town Meeting learned that all of the soldiers would not be immediately moved out of town, tension began to rise again to the point that Secretary of State Andrew Oliver later said if the troops had not been removed, the town likely would have risen up against them and "that they would probably be destroyed by the people - should it be called rebellion, should it incur the loss of our charter, or be the consequence what it would."

At first, Hutchinson complained that he did not have the authority to remove the troops. Lt. Col. Dalrymple was the highest military officer in the city and he did not volunteer to move the troops out either. Hancock told Hutchinson that if the troops were not removed immediately 10,000 citizens would march on them.

Adams told Hutchinson, "Sir, if the Lieutenant Governor or Colonel Dalrymple, or both together, have the authority to remove one regiment, they have the authority to remove two, and nothing short of a total evacuation of the town, by all regular troops, will satisfy the public mind or preserve the peace." Adams later wrote of Hutchinson at this moment, "I thought I saw his face grow pale, and I enjoyed the sight."

Hutchinson and the Governor's Council caved and it was agreed that the troops would be removed from the city to Castle William, a fort in Boston Harbor on Castle Island. The 14th Regiment was moved about a week later and the 29th shortly afterwards. As the soldiers marched to the wharf, Boston celebrated. The Sons of Liberty escorted the humiliated soldiers to the docks and people celebrated in their best clothes.

The funerals for the four victims who had already died were held on March 8 and the victims were buried at the Old Granary Burial Ground to great fanfare with thousands of onlookers. Shops were closed in mourning and protest. Church bells rang all over the city. Some estimated the crowd at over 10,000 people, or more than half the population. The fifth victim, Patrick Carr, did not die until the 14th and was buried with the others on the 17th.

Paul Revere engraving of the Boston Massacre

In the days following the Boston Massacre, numerous artists and writers went about depicting the events that occurred, chiefly to express outrage against the British and to rally colonial opposition throughout Massachusetts and the other colonies against them.

The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street, Boston on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regiment by Paul Revere

The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street, Boston on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regiment by Paul RevereHenry Pelham, who was a half-brother to John Singleton Copley, one of the most famous artists of the Revolutionary period, created an engraving of the massacre. Paul Revere and others copied this engraving, with their own flourishes and it soon became the most recognizable image depicting the Boston Massacre, even to this day. Revere was the better marketer, however, and his version became the most copied and reprinted picture of the event, even though Pelham protested plagiarism.

Revere's engraving was called The Bloody Massacre perpetrated in King Street, Boston on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regiment. Note that at this time the phrase, "Boston Massacre," was not yet used to describe the event. It was Revere who first used the word "Massacre" on this engraving. The term "Boston Massacre" did not really catch on until the Civil War period.

Revere's engraving was used to communicate the position of the patriots, which was that the British soldiers were the aggressors. It served as a piece of "propaganda" to depict their viewpoint. Several factors in the engraving are clearly wrong or were changed to reflect their views. For example, Captain Preston is seen giving the order to fire on the crowd, a fact which was disproved during the trial several months later. The soldiers are also shown standing in a straight line, as if in battle formation, when the truth is that they were surrounded by a crowd with their backs against the wall.

Notice also that there is no sign of any weapons amongst the colonists, which is a complete misrepresentation of the truth. The colonists were attacking the soldiers with sticks, clubs, lumps of coal, mud, ice, oyster shells and anything else they could find, but there is not a trace of these things in the engraving. This all makes it appear that the soldiers were firing on a peaceful and innocent group of bystanders, murdering them in cold blood.

This picture shows the gun in the second floor window of the Custom House in Paul Revere's Boston Massacre engraving. (It's more clear in the enlargement)

This picture shows the gun in the second floor window of the Custom House in Paul Revere's Boston Massacre engraving. (It's more clear in the enlargement)A few other points that are not accurate in the engraving are that there is no snow on the ground and the scene appears to be in the daytime. In reality there was a lot of snow on the ground and it was 9 o'clock at night.

Finally, there is a musket pointing out of the Custom House window toward the civilians. Some people claimed that there were additional soldiers who fired from the Custom House's second floor. Indeed, a few civilians were charged along with the soldiers for firing out of the Custom House, but they were not convicted. The identity of any shooters in the Custom House, or if they even existed, was never proven definitively and still remains a mystery.

Some have complained that the mulatto former slave, Crispus Attucks, is not depicted as being a black man in the Paul Revere engraving. The man on the ground in the middle of the painting and nearest to the soldiers is clearly Attucks and he appears to be white. This may or may not have been a deliberate attempt to portray all the victims as white British citizens. However, several of the original prints were colorized by local Boston artist Christian Remick. Remick painted the soldiers' red coats, the townspeople, the blood and so on. In several of these early prints, Attucks is clearly depicted with a darker shade of skin. Whether or not Attucks appears as white in other versions on purpose or whether it was unintentional, will never be known for sure.

Written accounts of the Boston Massacre

In addition to Revere's engraving, several written accounts of the Boston Massacre were widely distributed in the days and months after the event. Captain Preston published a deposition on March 12, only one week after the event. In it, he claimed he did not order the soldiers to fire on the civilians, but that they acted in self-defense when they were being attacked.

Preston also wrote a published letter to the town of Boston, in which he thanked the city for giving him the chance to prove his innocence of the charges in court. He also sent a private letter to London, which was much more critical of the colonists. In it, he called the colonists "malcontents," accused them of "grossly and falsely promulgating untruths" and contempt against the soldiers, "promoting and aiding desertions and manufacturing the idea that the shooting "was a concerted scheme to murder the inhabitants." This letter later found its way back to Boston and was published in June, causing the public to turn against him.

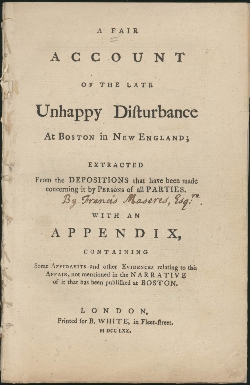

A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New England

A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New EnglandAt the direction of General Gage, Lt. Col. Dalrymple ordered the gathering of depositions from eyewitnesses, mostly soldiers, to tell the Boston Massacre from their perspective. Dalrymple's depositions left Boston on March 16th with Commissioner John Robinson for London. The 31 depositions were gathered into a pamphlet called A Fair Account of the Late Unhappy Disturbance at Boston in New England. The pamphlet made it seem as if the soldiers were completely innocent and it was all the colonists' fault. It blamed the colonists for their lack of deference to Parliament's authority to tax them and accused them of planning the attack against the soldiers.

An excerpt from A Fair Account:

"Mr. John Gillespie, in his deposition, (No. 104) declares that, as he was going to the south end of the town, to meet some friends at a public house, he met several people in the streets in parties [armed with clubs], to the number, as he thinks, of forty or fifty persons; and that while he was sitting with his friends there, several persons of his acquaintance came in to them at different times, and took notice of the numbers of persons they had seen in the street armed in the above manner... About half an hour after eight the bells rung, which he and his company took to be for fire; but they were told by the landlord of the house that it was to collect the mob. Mr. Gillespie upon this resolved to go home, and in his way met numbers of people who were running past him, of whom many were armed with clubs and sticks, and some with other weapons. At the same time a number of people passed by him with two fire-engines, as if there had been a fire in the town. But they were soon told that there was no fire, but that the people were going to fight the soldiers, upon which they immediately quitted the fire-engines, and swore they would go to their assistance. All this happened before the soldiers near the custom-house fired their muskets, which was not till half an hour after nine o'clock; and it shows that the inhabitants had formed, and were preparing to execute, a design of attacking the soldiers on that evening."

A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre was put together by the Boston Town Meeting and primarily written by James Bowdoin, a member of the Governor's Council and an important political leader in Massachusetts in the years to come. Bowdoin was assisted in the writing by Samuel Pemberton and Dr. Joseph Warren, who would later die at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

This report was intended to counter the soldiers' testimony and make it seem that the colonists were innocent and it was all the soldiers' fault. The report included 96 depositions from eyewitnesses to the Boston Massacre. These accounts are the source of much of the information we know about the fight at Gray's Ropewalk, the marauding soldiers prior to the massacre and the actual shooting itself. A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre became one of the most read accounts of the Boston Massacre and largely shaped the rest of the colonies' opinions and ideas of what happened there.

Another version of the Boston Massacre events is known as the Anonymous Account of the Boston Massacre. This is actually a shortened version of A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre, which was published by an anonymous person in Boston newspapers. Scholars speculate its author was Samuel Adams.

The Boston Massacre TrialsA grand jury was appointed the very next week following the Boston Massacre to examine the evidence against the soldiers. They began deliberations on March 13th and on the 27th indicted Captain Preston, the eight soldiers and four civilian employees of the Custom House for murder. This meant they believed there was sufficient evidence to take the matter to trial. Preston's letter to London condemning the townspeople was published in Boston during this time, which didn't help their case any.

Boston Massacre, 1770 by Constantino Brumidi Fresco in room S-128 of the US Capitol

Boston Massacre, 1770 by Constantino Brumidi Fresco in room S-128 of the US CapitolMuch effort was spent trying to determine which, if any, civilians employees of the Custom House fired on the crowd from the second floor window of the Custom House. Seven people testified they saw shots coming from the window. A French servant boy of Boston's tide surveyor, Edward Manwarring, claimed that he and several others had fired from one of the windows at Manwarring's direction.

This testimony was definitely proven false when several servants said they were in the house alone and the officials in question proved that they were at other locations. The boy recanted his testimony and was put in jail for lying to the authorities, but Manwarring, customs officer John Munro, notary public Hammond Green and servant Thomas Greenwood all spent time in jail after the Grand Jury ruled against them, having spent days interviewing the Custom House servants, Hammond Green's children and the officials.

The judgment from the Grand Jury against these civilians shows how strong the public fervor was to add more Custom House officials to the list of guilty people for the Boston Massacre, in spite of the fact that the officials provided rock solid alibis.

Lt Governor Hutchinson did not want to see British soldiers or customs officials convicted for cold-blooded murder. He did, however, want to see a fair trial take place to ensure the citizens that the government was working for them and in their behalf to see justice done. He also knew that if a trial were to be conducted right away, the soldiers most likely would be found guilty due to the feverishly high emotions in the town at the time.

The situation in the town was so tense that Hutchinson recommended to Sheriff Stephen Greenleaf that he take the keys to the jail from the jailkeeper each night in case the mob would attack the jail and overpower him and try to lynch the soldiers.

Rumors spread around Boston that the King would pardon the soldiers if they were convicted. This only fanned the flame to see justice done, meaning the conviction of the soldiers. Others rumors swirled that whether a guilty conviction was made or not, the townspeople would lynch the soldiers.

Picture from Boston's annual reenactment of the Boston Massacre

Picture from Boston's annual reenactment of the Boston MassacreAt the suggestion of General Gage, Hutchinson held the trials back as long as he could, to let tempers simmer down and reason prevail. Formal murder charges were not delivered until September 7th. In the end, three separate trials were held, one for Captain Preston alone in October, a second for the other eight soldiers in December and a third for the four Custom House employees, also in December.

In spite of the fact that the colonists were outraged with the soldiers behavior, many were equally concerned with the actions of the mob against the soldiers. They did not want foreign soldiers occupying their town, but they also did not want local citizens forming mobs and exacting justice on people at will. They wanted law and order and also wanted to see a fair trial take place.

There were numerous motives and concerns among different groups in Boston at this time. Patriots wanted to see all the soldiers convicted. Royal officials and Loyalist citizens hoped they would be pardoned or the charges would be dropped. If the soldiers did not get a fair trial, the British government might retaliate and take actions against the colony. Loyalist citizens might be turned off as well, hardening them against the patriot position.

On the other hand, the British government was put in the awkward position of trying its own soldiers for murdering civilians, even though they were about to be killed. If the soldiers were found innocent they feared an all out rebellion complete with lynchings of the soldiers and other public officials. It was in the interest of everyone involved that the soldiers receive a fair trial. It was also in the interest of most parties that the soldiers be found innocent by reason of self-defense and that the blame be put on the mob for taking justice into their own hands.

John Adams

John AdamsThe day after the Boston Massacre, 34 year old lawyer John Adams, who was one of Boston's most prominent attorneys, received a visitor at his home. James Forest was a friend of Captain Preston who was trying to find a lawyer to represent Preston at the trial. In tears, Forest told Adams that nearly everyone he approached had turned him down and expressed outrage at the idea of defending someone who they viewed as the arm of the tyranny of the British government. Two lawyers, however, Josiah Quincy II and Robert Auchmuty, expressed an interest in taking the case, but with one condition, that John Adams agree to be the lead attorney.

Forest expressed that Captain Preston was quite desperate and pleaded with Mr. Adams to take the case. John Adams knew that taking the case would bring down a great deal of criticism from his fellow citizens. They would accuse him of helping the enemy, his business might suffer and his family might even be in danger. He also believed that every person deserved a fair trial and that mob action was against the law. He decided that if he was needed and if the other two attorneys would help, he would take the case, regardless of how it affected his career.

Josiah Quincy II

Josiah Quincy IIIn the end, Adams, Quincy, who was an ardent patriot and Auchmuty, who was an ardent Loyalist and judge of the Vice-Admiralty Court, would represent the captain. The soldiers would be represented by Adams, Quincy and Sampson Salter Blowers, instead of Auchmuty, to examine the jury pool. Paul Revere would assist them by drawing a detailed map of the scene of the Boston Massacre.

The prosecution was handled by Solicitor General Samuel Quincy and attorney Robert Treat Paine, a future signer of the Declaration of Independence, who was hired by the Boston Town Meeting for the trial. Solicitor General Quincy and defense attorney Josiah Quincy were brothers.

The trial of Captain Preston

The trial of Thomas Preston began on October 24, 1768 in Boston's new courthouse on Queen Street and lasted for five days, an unusually long trial in those days since no previous criminal trial had lasted longer than a day!

The main issue to be decided during the trial of Captain Preston was whether or not he ordered the soldiers under his command to fire their weapons. If he had, then the blame lay with him and the soldiers were not guilty because they were following orders. If he had not given the order, the soldiers were guilty of firing on civilians without orders.

In those days, it was common for officers or other high officials to be tried separately, even though the trials concerned the same events. On the day the trial was to begin, several of the soldiers appealed that they should be tried together with Captain Preston. Their concern was that Preston would be found innocent of giving the order to fire on the civilians. If he was found to be innocent, that automatically meant they had fired without orders. This would be an act of murder and the punishment was death.

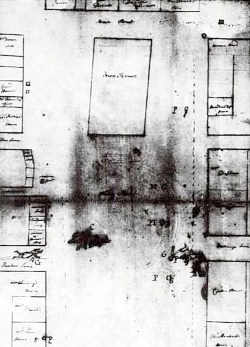

Paul Revere Boston Massacre Diagram Revere's drawing was submitted as evidence in the trial. It looks like a modern day crime scene report. The A and G in the lower left show the bodies of Crispus Attucks and Samuel Gray. The G on the right shows the body of Samuel Maverick, identified with a G because his master's name was Greenwood. James Caldwell is identified with a C in the center of the drawing Captain Preston is identified with a P in the lower right corner. You can also see the Custom House to the right and the Town House in the upper center.

Paul Revere Boston Massacre Diagram Revere's drawing was submitted as evidence in the trial. It looks like a modern day crime scene report. The A and G in the lower left show the bodies of Crispus Attucks and Samuel Gray. The G on the right shows the body of Samuel Maverick, identified with a G because his master's name was Greenwood. James Caldwell is identified with a C in the center of the drawing Captain Preston is identified with a P in the lower right corner. You can also see the Custom House to the right and the Town House in the upper center.Click here for Enlarged Version

Instead, if the soldiers could be tried with Preston, they would be able to present the case that they were only obeying his order to fire and were therefore not guilty of breaking the law or committing murder. This put their attorneys in the unusual position of arguing a defense for Captain Preston that might harm the soldiers in the second case.

The soldiers' request was denied and they were tried separately from Captain Preston. This probably worked to the soldiers advantage though because of the fervor to convict someone. If Preston was found to be guilty of giving the command to fire, but the soldiers were innocent, if they were tried together there was a likelihood that they would all be convicted together. If they were tried separately, there was a higher likelihood that separate verdicts would be reached. Either way, there was risk to the soldiers.

The jury in Preston's trial was stacked with people who were favorable to Preston, including a few personal friends. The courtroom was packed with onlookers, but remained respectful and at peace according to Lt. Col. Dalrymple.

15 witnesses were called by the prosecution to prove that Preston had ordered the soldiers to fire. John Adams and his 23 witnesses argued that Captain Preston did not give the order to fire. Instead, they argued that the soldiers acted of their own accord under threats and intimidation, firing their weapons in the heat of the moment in self-defense.

Preston was not allowed to speak at the trial. In those days, it was standard procedure that an accused person could not speak in his own defense because his self-interest was believed to taint the reliability of his testimony. Preston did say, in his deposition, however, that he did not order the men to fire. Indeed, he diligently tried to stop them from firing once they had begun, even to the point of physically stopping them, grabbing their guns and pushing them upwards so as not to hit anyone. This fact was verified in some of the eyewitness testimonies as well.

Since the transcript of the trial has not survived, we will look at Preston's testimony from his deposition, which states:

"Some well behaved persons asked me if the guns were charged. I replied yes. They then asked me if I intended to order the men to fire. I answered no, by no means, observing to them that I was advanced before the muzzles of the men's pieces, and must fall a sacrifice if they fired; that the soldiers were upon the half cock and charged bayonets, and my giving the word fire under those circumstances would prove me to be no officer. While I was thus speaking, one of the soldiers having received a severe blow with a stick, stepped a little on one side and instantly fired, on which turning to and asking him why he fired without orders, I was struck with a club on my arm, which for some time deprived me of the use of it, which blow had it been placed on my head, most probably would have destroyed me. On this a general attack was made on the men by a great number of heavy clubs and snowballs being thrown at them, by which all our lives were in imminent danger, some persons at the same time from behind calling out, damn your bloods -- why don't you fire. Instantly three or four of the soldiers fired, one after another, and directly after three more in the same confusion and hurry."

According to other depositions, a few people claimed they did indeed hear Preston give the order to fire. Some witnesses said they heard someone order the men to fire, but couldn't say exactly who it was. Some accounts give the impression that Private Montgomery himself was pleading with his comrades to fire as he was being attacked. Numerous people in the crowd were shouting "fire" because they were daring the soldiers to shoot at them.

General Henry Knox

General Henry KnoxAnd then there were the people shouting "fire" because of the church bells ringing, which was the alarm to signal that a fire was burning to draw people out to help put it out. Henry Knox, the future Revolutionary War general, testified for the defense saying that the crowd was shouting "Fire, damn your blood, fire!" It's easy to see how the soldiers could have become confused about who was yelling "fire" and could have fired their weapons mistakenly, believing they were getting the order from Captain Preston.

Preston also stated in his deposition that he believed Private White, the Custom House sentry, would have been killed by the mob if he had not intervened. He also said that he believed the King's money, which was held in the Custom House was in danger of being looted and was the crowd's main objective.

In the end, the testimonies of the prosecution's witnesses were too contradictory to prove anything and the defense witnesses seemed more credible. For example, Richard Palmes, the man who asked Preston if the guns were loaded and got the crowd to disperse earlier from Murray's Barracks, testified he had his hand on Preston's shoulder when the order to fire was given, even at that close distance, he said he couldn't be sure it was Preston who gave the order.

The jury found Preston innocent of the charges on the basis of "reasonable doubt," a term that had never been used before, but would turn into the standard by which criminal convictions are judged in the American legal system.

Castle William on Castle Island in Boston Harbor, 1789

Castle William on Castle Island in Boston Harbor, 1789A few days after the trial, Captain Preston fled to Castle William to avoid a cascade of civil suits brought against him as a result of the massacre. He stayed there to help direct the defense of the soldiers from afar until the trial was over. The day after the soldiers' trial was over, however, he left for England where he retired from the army.

Some sources say he received 200 pounds from the Crown as compensation for his trouble in Boston, while others say he received 200 pounds a year as an annual pension. He is believed to have settled in Ireland, where he was from.

Preston's parting words when he left Boston were written to General Gage, in which he stated, "I take the liberty of wishing you joy at the complete victory obtained over the knaves and foolish villains of Boston." Gage seemed to be in agreement, he wrote later that year, according to David Hackett Fischer's book Paul Revere's Ride, that, "America is a mere bully, from one end to the other, and the Bostonians by far the greatest bullies."

John Adams recounted later that he received eighteen guineas, a very

small amount of money, from Preston as payment for his service, but

that he never received a thank-you from him since Preston was in such a

hurry to get out of Boston after the trial. He did however, claim to see

Preston on the streets of London once when he lived there in the 1780s.

John Adams later wrote that he believed his service to the Boston Massacre soldiers was the greatest act of his life.

The trial of the Boston Massacre soldiers

The trial of the Boston Massacre soldiers, formally known as Rex v. Weems et al, began on December 3, 1770 and lasted two days. As with Preston, the soldiers were not allowed to speak in their own behalf. The soldiers were on the hot seat from the start since it was already determined that Captain Preston had not ordered them to fire. They had fired on an unarmed crowd of civilians without legal permission or authority to do so. The only possible defense they could have now was that they were acting in self-defense. If they were convicted of murder, they would face the death penalty. If the self-defense argument was accepted, they would go free.

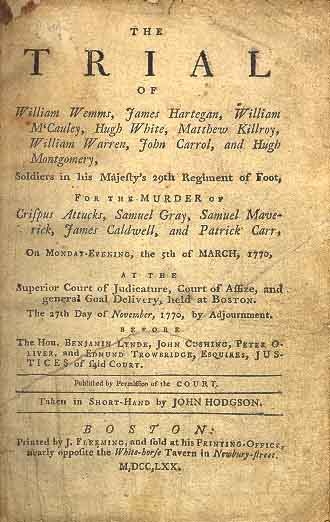

Trial of the Boston Massacre soldiers transcript cover

Trial of the Boston Massacre soldiers transcript coverThe jury was one hundred percent made up of citizens from outside Boston because it was believed most of the citizens of Boston would judge the soldiers guilty, regardless of the facts. They were anxious to see someone punished. One potential juror at the trial even stated, "he believed Captain Preston was innocent, but innocent blood had been shed and somebody ought to be hanged for it."

In his defense, John Adams argued that the jury must not convict them simply because they were angry with the soldiers for what happened. Instead, they must vote on the evidence. If the soldiers fired on the crowd for no good reason, they were guilty of murder and should be convicted. However, if they were being threatened and were in danger, firing in self-defense was justified and legal.

In his closing argument, Adams argued:

"I will enlarge no more on the evidence, but submit it to you.-Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence: nor is the law less stable than the fact; if an assault was made to endanger their lives, the law is clear, they had a right to kill in their own defence; if it was not so severe as to endanger their lives, yet if they were assaulted at all, struck and abused by blows of any sort, by snow-balls, oyster-shells, cinders, clubs, or sticks of any kind; this was a provocation, for which the law reduces the offence of killing, down to manslaughter, in consideration of those passions in our nature, which cannot be eradicated. To your candour and justice I submit the prisoners and their cause."

Josiah Quincy and John Adams clashed in their strategy to defend the soldiers. Quincy advised Adams to recount the numerous incidents of harassment from the citizens of Boston against British soldiers over the previous 18 months to establish a regular pattern of violence against them, in order to show that the soldiers had more than enough cause for concern for their safety. Adams ignored this advice. He even went so far as to announce that he would quit the trial if any more witnesses were brought forth whose sole purpose was to defame the town, witnesses which Quincy had prepared!

Adams also thought Quincy was cross-examining the prosecution's witnesses too aggressively, giving them too much opportunity to give evidence that would support the prosecution's claims. Adams urged him to abort this strategy as well.

Adams argued that the real fault lay with the policies of Parliament that had put the soldiers in the position they were in. He said any time "soldiers were quartered in a populous town" they would tend to cause disgruntlement in the population and would encourage them to riot. This possibility was "in direct proportion to the despotism of the government."

Boston Massacre victims grave Old Granary Burial Ground Boston, Massachusetts

Boston Massacre victims grave Old Granary Burial Ground Boston, MassachusettsThe complete transcript of this second trial has survived. One of the most effective testimonies on the prosecution's side turned out to be that of Samuel Hemmingway who testified he had heard Private Matthew Kilroy say "he would never miss an opportunity, when he had one, to fire on the inhabitants, and that he had wanted to have an opportunity ever since he landed." In addition to this damning statement, Kilroy had also been one of the soldiers involved in the skirmish at Gray's Ropewalk three days earlier and may have had a score to settle.

One interesting aspect of the trial is that the testimony of Patrick Carr was allowed as evidence, since he was dead. Carr was the last of the victims of the Boston Massacre to die. Being from Ireland, which had also endured a bloody occupation by the British, Carr was very familiar with strife between citizens and soldiers.

Carr confessed to a Doctor John Jeffries, who tended him, that he didn't blame the soldiers because they were being so severely harassed. In fact, he said he wondered why they hadn't fired sooner. Carr's deathbed testimony to Dr. Jeffries was allowed as evidence because it was believed that a dying man, about to meet his maker, would not lie. Other than this, second hand or hearsay testimony, is normally not allowed in court.

This testimony, along with more than 40 others, helped establish the idea that the soldiers had acted in self-defense and not malice. Adams painted the crowd as "a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and mullatoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tarrs," that was threatening the solders with their lives and was the source of the conflict.

Adams asked the jury, would "it have been a prudent resolution in them, or in any body in their situation, to have stood still, to see if the [the mob] would knock their brains out, or not?" Justice Edmund Trowbridge, instructing the jury, said that "malice is the grand criterion that distinguishes murder from all other homicides."

The trial lasted 2 days and the jurors deliberated for only two and a half hours before delivering their final verdict. They found two of the soldiers guilty of manslaughter, reduced from murder, and six of them were found innocent for lack of evidence. The jury indicated that they believed the soldiers were indeed being threatened, thus the reduction in the conviction to manslaughter, but they also believed they acted in haste and should have restrained themselves.

The jury convicted two of the soldiers for the Boston Massacre tragedy because of overwhelming evidence that they had fired into the crowd. More of them may have been convicted if the evidence had been more concrete. In the confusion of the moment, it was simply too hard to determine who had fired upon whom or whose shot killed which person.

Hugh Montgomery was convicted of manslaughter for the death of Crispus Attucks, the first person to die in the incident. Montgomery was the soldier Attucks allegedly attacked and from whom he tried to take his weapon.

Matthew Kilroy, the soldier involved in the Gray's ropewalk scuffle, was charged with manslaughter for the death of Patrick Carr, the Irishman who didn't blame the soldiers.

The soldiers were sentenced a week later on December 14th. In the meantime, Captain Preston, who had fled to Castle William after his own trial to avoid mounting civil lawsuits, left for England the day after the soldiers' trial ended, never to return.

The Boston Massacre, 5th March, 1770 by Alonzo Chappell