The Stamp Act -

March 22, 1765

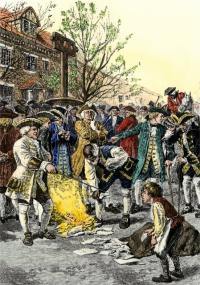

The Stamp Act was one of the leading causes of the Revolutionary War. It required that many documents such as licenses, diplomas, contracts and even playing cards be printed on embossed (or stamped) paper that had a tax on it. Parliament intended to use the tax to help pay the expenses of British troops on the frontier, but instead the colonists reacted with fury as they torched the homes of stamp distributors, captured stamps and destroyed them and completely refused to comply with the act.

The issue they were so angry about? Taxation without representation! They had no representatives in Parliament and believed the Stamp Act clearly violated their right as English citizens to have taxes laid only by those whom they had elected. You can read more about the history and impact of the Stamp Act below.

Background of the Stamp Act of 1765

There was a series of causes leading up to the American Revolution that took place over many years, most having to do with taxation. The Molasses Act, the Proclamation of 1763, the Currency Act and the Sugar Act, all caused resentment by restricting colonial trade and ingenuity, in order to benefit the mother country at the colonists' expense.

The Stamp Act, however, took things to a whole new level. The Stamp Act marked Parliament's very first attempt to tax the colonists directly for activity that occurred solely within the colonies themselves. All prior taxes had to do with regulation of shipping. Small fees were placed on imports and exports to raise some money, but also to control the flow of goods and resources. Parliament attempted to keep trade within the British Empire by placing higher taxes on goods traded with foreign countries in order to create higher demand for British made goods. If you would like, go back to our Revolutionary War Causes page and follow each article chronologically to get a better idea of the sequence of events that took place before the passage of the Stamp Act.

The Stamp Act was different than the other acts that upset the colonists earlier. This is because the Stamp Act was an internal tax. Colonists considered taxes to be internal taxes or external taxes. An internal tax was a tax on common, daily activities that originated and ended solely within the colonies themselves, in the local marketplace, while an external tax had to do with activities that occurred only partly in the colonies, but also partly outside.

Trade was considered to be an external activity because a foreign entity of some kind was involved on the other end to supply or receive whatever goods were being shipped. External taxes on trade were considered to be perfectly reasonable and legal by the colonists. They had a very different view of internal taxes though. They believed internal taxes were completely evil and amounted to the robbery of finances due to greed and corruption on the part of the taxing body.

So why did Parliament pass the Stamp Act to begin with, suddenly changing its longstanding policy of imposing only external taxes on trade? The events of the French and Indian War caused the change. The war was fought from 1757 - 1763 and spanned the globe, involving England and her allies and the French and her allies from India to Africa to Europe to America. England won the war and part of the final peace agreement included France giving up her American territory to England.

The victory came with a huge cost though, the British national debt skyrocketed during the war and the administration of Prime Minister George Grenville was eager to pay it down before the interest payments bankrupted the government. In addition, the previous administration of Lord Bute had placed 10,000 British troops on the new frontier to protect the lands that were gained by England during the war. This added expense only served to make the debt go higher. Prime Minister Grenville reasoned that it was only fair for the colonists to pay for at least a portion of their own defense and tried to find a reasonable way to raise money from them for the purpose. Read more about the reasons Britain posted so many troops in post war colonial America at the Proclamation of 1763 page.

Warnings about passing the Stamp Act

Prime Minister Grenville created a series of acts to deal with the huge national debt and pay for the troops in North America. The Currency Act forbade the colonies from printing their own money in an effort to stabilize the money supply. The Sugar Act was passed in order to increase trade and business within the Empire by taxing trade with foreign partners. The Stamp Act was another part of Grenville's plan to reduce the national debt. It cost an estimated 350,000 pounds to finance the troops and Grenville estimated the Stamp Act would raise about 60,000 pounds of the cost.

When the Sugar Act was passed in April of 1764, Grenville mentioned that a stamp tax was being considered for the future. He specifically asked the colonists for their opinions on how best to implement such a tax and requested they give their suggestions if they had any better options in mind. Some historians conclude from this that Grenville was not purposefully trying to aggravate the colonists. They believe he was genuinely trying to find the best way to reduce the debt and trying to include those who would be affected in the decision making process.

Others have concluded that this was merely a pretense by Grenville. They believe he didn't really care what the colonists had to say about it, but think he was using this as a tactic to merely give the appearance that he was trying to include them so he couldn't be blamed for forging ahead with the tax later. He knew the tax would be unpopular and was trying to give himself some cover by creating an alibi, in their view, the alibi being that he tried to get the colonists to come up with a better suggestion, but since they had none, he had to go forward with the tax.

In reality, because Grenville's request was so vague, the colonists didn't come up with any better suggestions. Grenville's request didn't specify time frames or amounts or rates so they didn't quite take it seriously. The idea that they would be taxed with such an internal tax was incomprehensible to the colonists. They simply didn't believe that Grenville would go through with it. The fact that Grenville's request was not more specific also lends to the idea that his asking the colonists for their suggestions was merely for show. Had he been serious about it, he probably would have given much more specific details and goals. In the end, the colonists' inaction provided him exactly the excuse he was looking for. Both Grenville and Parliament did receive warnings, however, that the colonists would never submit to such an internal tax and that their response could be quite vehement. Of course, these warnings weren't taken seriously by Grenville and he went ahead with his plan.

Some of these warnings came from the colonial legislatures themselves. By the end of 1764, eight colonial legislatures had sent letters to Parliament protesting the Sugar Act and the forthcoming Stamp Act. Though worded in different ways, each one concluded that Parliament had no right to tax them without their consent. By the end of 1765, all the colonies but North Carolina and Georgia had sent similar letters.

You can read the formal complaints from New York, Massachusetts and Virginia here:

- New York Petition to the House of Commons, October 18, 1764

- Massachusetts Petition to the House of Commons, November 3, 1764

- Virginia Petition of the House of Burgesses to the House of Commons, December 18, 1764

On February 2, 1765, Prime Minister Grenville met with Benjamin Franklin, Jared Ingersoll, Richard Jackson and Charles Garth, who were all representatives from various colonies to Parliament, to discuss the upcoming act. The colonial representatives had no alternative proposals in mind and said it should be left up to the colonial legislatures to decide. Grenville said he wanted to lay the tax "by means the most easy and least objectionable to the Colonies." Thomas Whately, Grenville's secretary, who drafted the Stamp Act, said the delay in passing the Stamp Act had been "out of Tenderness to the colonies" and the act was deemed to be "the easiest, the most equal and the most certain."

Grenville then submitted his annual budget to Parliament, including the Stamp Act. On February 12, Franklin and Thomas Pownall, a former Royal Governor of Massachusetts, met with Grenville to propose an alternative plan to raise the money. Their plan was to have the colonies issue paper money at interest, but Grenville ignored their proposal. Remember, he had already passed the Currency Act which banned the colonies from printing money?

Soon after, Parliament began a short debate over the passage of the Stamp Act. Jared Ingersoll, Connecticut's representative to the Crown, sat in the audience listening. The same day he wrote back to the Royal Governor of Connecticut, Thomas Fitch about what had transpired. Several famous quotes come from this letter which relates an exchange during the debate between Charles Townshend and Isaac Barré. At one point, Charles Townshend, who would be the later author of the Townshend Acts, which further aggravated the colonists, asked:

"...and now will these Americans, children planted by our care, nourished up by our Indulgence until they are grown to a degree of strength and opulence, and protected by our arms, will they grudge to contribute their mite to relieve us from the heavy weight of the burden which we lie under?"

The witty response was given by Isaac Barré, an Irish politician who had served in the colonies during the French and Indian War and was present at the defeat of Quebec during that war. Barré became a fierce advocate of the colonies in Parliament. In response to Townshend's question, he replied:

"They planted by your care? No! Your oppression planted 'em in America. They fled from your tyranny to a then uncultivated and unhospitable country where they exposed themselves to almost all the hardships to which human nature is liable, and among others to the cruelties of a savage foe, the most subtle, and I take upon me to say, the most formidable of any people upon the face of God's earth..."

They nourished by your indulgence? They grew by your neglect of 'em. As soon as you began to care about 'em, that care was exercised in sending persons to rule over 'em, in one department and another, who were perhaps the deputies of deputies to some member of this house, sent to spy out their liberty, to misrepresent their actions and to prey upon 'em; men whose behaviour on many occasions has caused the blood of those sons of liberty to recoil within them...

They protected by your arms? They have nobly taken up arms in your defence, have exerted a valour amidst their constant and laborious industry for the defence of a country whose frontier, while drenched in blood, its interior parts have yielded all its little savings to your emolument. ...The people I believe are as truly loyal as any subjects the king has, but a people jealous of their liberties and who will vindicate them if ever they should be violated; but the subject is too delicate and I will say no more."

You can read the entire Jared Ingersoll letter to Thomas Fitch from February 11, 1765 relating this story here.

Barré's use of the phrase "sons of liberty" in this speech is the origin of the phrase used by the colonists to describe their secret organizations involved in resistance to the British government. Groups formed in all the colonies to exchange information, enforce non-importation agreements and plan resistance activities. These groups were meeting before Barré's speech and the term had probably been used before, but it became popularized as a result of the speech as it was spread around the colonies in newspapers.

Women and girls formed "Daughters of Liberty" groups as well, pledging to make their own cloth at home to put pressure on British merchants in hopes of forcing them to lobby Parliament to repeal the Act. The Sons of Liberty even developed their own flag, known as the Sons of Liberty Flag, which was often flown from "Liberty Trees" where colonists met to plan resistance against the authorities.

In spite of the colorful defense of the colonists by Barré and others, the Stamp Act passed 205-49 in the House of Commons and only five voted against it in the House of Lords, including Lord Charles Cornwallis, the same general who would later be defeated at Yorktown at the end of the Revolutionary War. The Stamp Act was given royal assent on March 22, 1765. When word of its passage was received in the colonies, Governor William Tryon in North Carolina wrote to the King that he had interviewed John Ashe, the current Speaker of the House of Representatives in North Carolina, to gauge what would be the response of the colonists to the Stamp Act. Ashe told him this act would be "resisted to blood and death."

Provisions of the Stamp Act of 1765

The Stamp Act called for various items such as licenses, documents, diplomas and nearly every paper item to be printed on stamped or embossed paper. The paper had a tax on it and had to be bought from a government stamped-paper office. The stamp was not a stamp in the sense of a small piece of paper with glue on the back that is affixed to an envelope like we use today. Instead a more similar modern day equivalent would be the notary stamp that is used to mark official documents. A notary public takes someone's official document, looks it over, observes them sign the document and records the transaction, then stamps the document with a hand pressed stamp that indents the paper with certain official words and symbols identifying the time, date and name of the notary.

This is similar to how the Stamp Act stamps worked. The raised stamp was imprinted on the paper and then the paper was sold to the customer. Another method that would have been used in the colonies involved the stamp being stamped on a small piece of blue paper that was affixed to the paper document by a small piece of tin foil attached to it. The tin foil was run through the paper and flattened on the back much like the clasp on a large Manilla envelope works today. Anyone caught using any documents without the proper stamp that were supposed to be printed on stamped paper would be breaking the law.

|

|

|

|

| There are fewer than 60 recorded instances of Stamps actually being used as required by the Stamp Act, most of them from Georgia or Quebec. Georgia was the only one of the 13 colonies that were to become the United States where stamps were used and then only for a period of one day. The differing types of stamps were used for different types of documents. You can click on each stamp to see a larger image. | |||

The Stamp Act called for the taxing of 54 separate items including diplomas, marriage licenses, newspapers, pamphlets, playing cards, court documents, legal proceedings, fines, legal licenses, shipping bills, contracts, liquor licenses, public appointments, grants, deeds, warrants, almanacs, calendars, playing cards and even dice (maybe they were wrapped in paper?)! These items were taxed anywhere from a few shillings (pennies) up to ten pounds. So basically most official documents or anything else printed on paper, anything less than a book, was taxed.

Stamps and stamped paper were to be created in England and shipped to America where they would be managed and sold by Stamp Distributors appointed by the Crown who were to be stationed in various cities around the colonies. The stamps had to be paid for in British sterling silver pounds, not in colonial paper currency. All of the money raised with the tax was to stay within the colonies and be spent on supplying and housing British troops and was not to be sent back to Britain. Prime Minister Grenville believed this would encourage the colonists to support the Act, because it would increase demand for those businesses supplying goods and services to the troops.

Under the Stamp Act, anyone accused of not having the proper stamp affixed to an item could be tried in an admiralty court. These were special courts normally reserved for maritime matters with different rules than typical courts. Admiralty courts had no juries, only Crown appointed judges who made more money when they found someone guilty. This was another point that alarmed the colonists beyond the "no taxation without representation" issue that most Americans are familiar with. English law gave the accused the right to a trial by jury and the colonists believed Parliament was stripping them of this valuable right. This is part of the reason why the first US Congress later guaranteed this right by including the Right to Trial by Jury Clause in the US Constitution's 6th Amendment.

In addition to the removal of trial by jury for violating the Stamp Act, the admiralty courts met in Nova Scotia! This meant that in order to defend oneself from charges of violating the Stamp Act, he had to travel to Nova Scotia to stand before a judge who was going to get paid more if he found the accused guilty! This was clearly an attempt by Parliament to force the colonists into obeying the provisions of the Stamp Act out of fear because not many would be able to risk the consequences of violating the act and being forced to travel to Nova Scotia to defend themselves.

Beyond the issues of "no taxation without representation" and the use of unjust admiralty courts that removed the right to trial by jury, the Stamp Act mentioned specifically, in relation to the taxation of court documents, those courts exercising "ecclesiastical jurisdiction," ecclesiastical referring to the church.

European countries often had separate religious courts that would try their members regarding alleged violations of religious beliefs and practices. The colonies had no such courts overseeing religious matters like they did in England and the colonists feared this was the first step to establishing them. Many colonists and their ancestors had fled England and other countries in order to avoid such government appointed religious institutions and the idea of creating them in America made them very nervous. So you can see that the colonists challenged the Stamp Act, not only because of its taxes, but the Act contained other issues that alarmed them as well.

Colonial Response to the Stamp Act

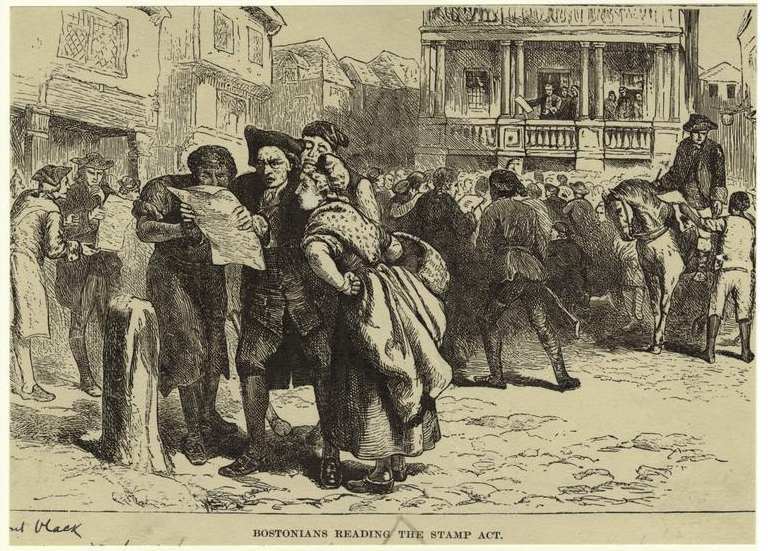

EVERYONE was surprised by the strong, unified and violent response of the colonists to the Stamp Act. Colonial legislatures met and wrote up formal complaints to Parliament and began to meet and cooperate in their efforts. Some Royal Governors refused to call their colonies' legislatures into session so they could not produce resolutions condemning the Stamp Act. Merchants organized boycotts of British goods. Mobs formed to intimidate Stamp Distributors and Royal Governors from enforcing the act. The colonists were surprised to realize they had such strength and Parliament was shocked to realize just how powerful their far away colonists had become. Their intimidation tactics were so successful that on November 1, 1765, the day the tax was to begin, there were ZERO stamp distributors left! Every single one resigned ahead of time, with the exception of the stamp distributor in Georgia... because he didn't arrive until January... and when he did? He resigned after one day!

November 1st was a somber day around the colonies, businesses and courts shut down, ships flew their flags at half mast and newspapers published with broad black lines across their pages. Starting that day, many forms of business shut down indefinitely because they could not lawfully conduct business without using the stamps and since there were no stamp distributors left, they could not lawfully engage in such common activities as getting married, writing a will or publishing a newspaper. Many newspapers were shut down by this time, unsure how to proceed, though some published anyway. Local officials were left to decide how they would respond. Some forbade local government offices from operating without stamps. In other places, officials commanded their employees to continue business as normal even without stamps, in defiance of the law.

Objections to the Stamp Act

The colonists did not have any objection to paying taxes, if those taxes were created by their own elected legislators. The British national debt grew substantially during the French and Indian War due to paying for soldiers and supplies, but the colonial legislatures paid a great deal of money for soldiers and supplies as well. The colonies all raised militias who served under British officers during the war. Each colony raised the money to pay its own soldiers through various kinds of taxes. So the colonists did not have a problem with paying taxes.

The issue with the colonists was also not the amount of the tax. The Stamp Act was only estimated to raise 60,000 pounds.

Instead, it was the fact that Parliament was trying to tax them and they had no elected representatives in Parliament. It was an established fact of English law that taxation could only be done by elected representatives. So the colonists believed Parliament was trampling on their right of taxation only being done by elected representatives. Each colony had its own elected government to deal with local matters. Colonists believed these bodies were the proper place for taxes to be raised, not by Parliament.

Some in Parliament tried to argue that they were in agreement with the colonists that taxation without representation was unjust, but, they said, the colonists were not without representation. They argued that the colonists had "virtual representation" in Parliament. In reality, about 75% of British males could not vote because the right to vote had certain requirements that had to be met, such as owning a certain amount of property or having attained a certain status in society. The theory of virtual representation held that, although these people were not represented by someone they elected, the other elected politicians did represent them in the sense that they had the good of all citizens in mind and not just their own constituents. The colonists, according to some, were "virtually represented," in the same way.

When the complaints from the colonies started making their way across the sea, Thomas Whately, Grenville's secretary, published a pamphlet called "The Regulations Lately Made Concerning the Colonies and the Taxes imposed upon them considered." In this pamphlet, Whately succinctly described the ministry's justification for the Act and explained why Parliament had a right to tax the colonists. He explained the principal of virtual representation and the wider view of Grenville's trade and economic vision for the empire as a whole. Whately listed many precedents that he said were forms of taxation already imposed by Parliament on the colonists, including customs duties and post office fees. Read The Regulations Lately Made Concerning the Colonies and the Taxes imposed upon them considered by Thomas Whately here for a clear view of the Grenville program and his justifications of the Stamp Act.

Of course, the colonists thought the idea of virtual representation was ridiculous. There was also a huge difference between the colonists and disenfranchised citizens in England. The colonists had their own elected legislatures and had had them for 150 years by this point. Most colonists rejected the idea of virtual representation because they believed that no politician would be so noble as to act in the interest of someone else. They believed all politicians should have a vested interest in the policies they were enacting. If politicians were elected from local regions they would personally have to live under the laws they created and pay the taxes they levied. Far off politicians in Parliament who weren't personally affected by their own policies and had no friends and neighbors to be held accountable to could not possibly be expected to have the interests of the colonists in mind.

The Grenvillites tried to rely on the theory of virtual representation to justify their tax scheme, but Grenville himself also tried to reason that the colonial assemblies were no different than the Scottish town councils who had only as much authority as Parliament granted them. He said they had no real authority of their own. Of course the colonial assemblies had been acting as equal bodies to Parliament in their own jurisdictions for 150 years, but Grenville chose to ignore that point.

13 Colonies Map - Halifax, Nova Scotia

13 Colonies Map - Halifax, Nova ScotiaIn addition to the issue of taxation without representation, the other constitutional issues the colonists were concerned with were the Stamp Act's use of juryless admiralty courts for violaters and the creation of ecclesiastical courts. Trial by jury of one's peers was another precious right long established in English law. Violaters of the Stamp Act were actually required to go to Halifax, Nova Scotia to defend themselves in a court with no jury. Ecclesiastical courts could be created under the act for the trying of various matters as well. For 150 years, colonists had their own judges chosen by their elected legislatures and they viewed the Stamp Act as a first step to abolishing their own courts in order to replace them with judges appointed by the Crown.

Stamp taxes had been used successfully in England for a hundred years at this point, so it is understandable that Parliament would see them as a legitimate source of revenue, but the colonists were not used to having everyday activities, such as buying a newspaper or writing a will, taxed. Because of the great distance between England and the colonies and because of the great expense of administering law, the colonies had been somewhat ignored and allowed to grow on their own. This policy is called "salutary neglect." Salutary means "producing a beneficial effect." So, for many years, England had neglected to do much in regards to governing the colonies and this was viewed as producing a beneficial effect, the benefits being that the colonies could grow on their own and provide resources and markets for England's merchants without costing England a huge amount of money to govern them. Instead, they were allowed to govern themselves. This caused the colonists to have a very independent spirit and they did not appreciate it when Britain suddenly began to take a greater interest in their day to day affairs. If they had sent letters, written out wills and played cards for so many years without being taxed for it, why should they be taxed for them now?

Another point of contention with the colonists was the alleged need for British soldiers to be stationed in North America. Lord Bute had placed them there after the French and Indian War, allegedly for the colonists' protection from Indian uprisings and to enforce British law in the new land gained after the war. Bute's real reason though may have had more to do with needing a place for commissioned officers, many who were well connected in Parliament, to have a place to serve. Letting go of so many men of high position would not have gone over well with the ruling class of England and standing armies were very unpopular in England. Stationing the men in America solved both problems. You can read more about this in our Proclamation of 1763 article.

The colonists however, did not believe they needed protection after the war was over. They wanted to get on with settling the new territory west of the Alleghenies. Benjamin Franklin informed Parliament that the colonists had protected themselves from Indians for many years when they were much fewer in number. They could certainly do so now that their numbers were into the millions!

Opposition to the Stamp Act soon became organized and widespread. Part of the reason the opposition became so well organized was that the Stamp Act tax fell most heavily on those with power and influence - businessmen, merchants, journalists, lawyers and the like. These are the people who conducted the most business using forms, contracts and documents to be taxed. Of course they didn't like it and they were well positioned to use their influence to sway public opinion.

Secondly, the Stamp Act not only affected the elite and wealthy. It also affected the average person who would buy things like newspapers and cards, or need a marriage certificate or a will. So in this way, everyone was affected by the tax. The elite and powerful were affected... the masses were affected. Parliament had angered everyone!

Actions against the Stamp Act

The colonists expressed their objections to the Stamp Act in three main ways - through the printing and distribution of newspapers and pamphlets, through mob violence and threats and through legislative action.

Newspapers and Pamphlets against the Stamp Act

|

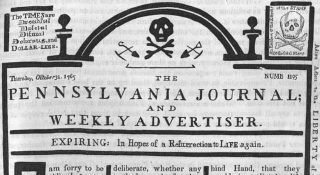

UPPER LEFT CORNER: The TIMES are Dreadful, Doleful, Dismal, Dolorous and Dollar-less. |

Header of Pennsylvania Journal for October 31, 1765 Header of Pennsylvania Journal for October 31, 1765 |

The publishers of newspapers were heavily involved in the Stamp Act opposition. Obviously the main reason was because the tax hit their form of business, publishing newspapers, squarely. When November 1 arrived, which was the official day for the beginning of the tax, newspapers across the colonies came up with all kinds of ways to avoid the tax. Some simply stopped publication. Others published anyway, but without the name and masthead on the paper so it wasn't obvious who had made the paper. Some printed openly in defiance of the law and put a skull and crossed bones where the stamp should have been affixed.

The leading newspapers of the day were intimately involved with the Stamp Act opposition, including the Massachusetts Gazette, Pennsylvania Gazette, Maryland Gazette, New Hampshire Gazette, North Carolina Gazette and Georgia Gazette. All of these publishers published various letters, pamphlets, criticisms, accounts of acts of mob violence against stamp distributors, etc. Most of them closed down on November 1, 1765, the official start date of the Stamp Act, in order to avoid violating the law by publishing without stamps.

In addition, many private citizens published letters and pamphlets explaining their positions about why the Stamp Act was illegal. These pamphlets and letters had an enormous effect on the general public and played a highly influential role in educating the public about their rights, stoking anti-Stamp Act sentiment and uniting the colonists into one frame of mind. A few of the most influential of these publications are mentioned here.

Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved was written by James Otis, a Massachusetts lawyer and public official, in response to the Sugar Act a year earlier, at which time Prime Minister Grenville also spoke of the probability that a stamp tax would be enacted. Otis argued that Parliament had no right to tax the colonists since they were not represented in that body. He also suggested that the colonists should elect members to Parliament, an idea that was not too popular with many colonists because they were used to having their own local legislatures who could respond immediately to their needs and wishes. They thought the small number of members they would be able to elect to Parliament would be vastly outnumbered by those elected from Britain.

Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved was important because it was officially adopted by the Massachusetts House of Representatives and was one of the first writings adopted by an elected governmental body to argue that the colonies' disagreement with Great Britain should be understood in terms of a violation of universal human rights. Otis wrote that Parliament had transgressed against the "Laws of Nature and Nature's God" by trying to tax them without representation. You can read Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved by James Otis here.

Of all the pamphlets and letters produced, the most widely read was Considerations on the Propriety of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies, by Daniel Dulany of Maryland, a wealthy lawyer and politician who was a member of the Governor's Council during the time of the Stamp Act crisis. In the pamphlet, Dulany argues that Parliament has supreme authority to legislate for the colonies in all matters except taxation, because taxation can only be justly and constitutionally ordered by elected representatives. He also condemns Joseph Whately's idea of "virtual representation."

Considerations on the Propriety of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies was the most widely read political pamphlet of 1765. It was reprinted all over the colonies and in London and had a great influence on the minds of the colonists. Several British statesmen also drew on Dulany's arguments in their own speech's before Parliament in support of the colonists, including William Pitt, the leading parliamentary voice against the Stamp Act. You can read Considerations on the Propriety of Imposing Taxes in the British Colonies by Daniel Dulany here. Unfortunately, in spite of his views against the Stamp Act, Dulany could never bring himself to resist the British government with more than protest. He remained a Loyalist throughout the Revolutionary War and much of his substantial landholdings were confiscated after the war.

Legislative action

Houses of Assembly and town councils across the colonies met and passed resolutions declaring the invalidity of the Stamp Act. They declared that no one had the right to tax them except their own elected legislatures. Eleven of the colonies sent letters to Parliament objecting to the idea of a stamp tax. Britain was stripping from them their rights as English citizens to be taxed by those whom they had elected. Britain was also taking from them their right to be tried by a jury of their peers.

On June 8, 1765, James Otis proposed to the Massachusetts Assembly House that they should invite all the colonies to meet and create a plan of joint resistance to the Stamp Act. This turned out to be a very pivotal event because it established the cooperative pattern that would be used by the colonists ten years later during the Revolutionary War. The Assembly agreed and sent a letter to the other colonies' legislatures, asking them to send representatives to meet in a continental congress in New York in October. The meeting came to be known as the Stamp Act Congress.

The Stamp Act Congress

The Stamp Act Congress met at New York City from October 7 to October 25, 1765, on Wall Street, in what would later become known as Federal Hall. The Massachusetts House of Representatives had voted on June 8 to call for all the colonies to meet to discuss a joint response to the Stamp Act. Nine colonies ended up sending representatives. The four that did not were Virginia, Georgia, North Carolina and New Hampshire. Virginia and North Carolina were not in session when their invitations arrived and so could not act. South Carolina was not in session either, but the Speaker of the House of Assembly, Alexander Wylly, called the legislators to Savannah anyway. 19 of 25 showed up. Governor James Wright was against the idea of the Stamp Act Congress and refused to call them into session, but Wylly met with them anyway and sent a letter to the Massachusetts Assembly with their blessing, stating the reasons why they could not send delegates, but affirming that they would support whatever actions the Congress agreed upon. New York had representatives at the Stamp Act Congress as well, but they were representatives from various counties and not from the state itself. Twenty seven delegates attended the congress and they represented the most elite citizens of the colonies, including politicians, lawyers, wealthy merchants and landowners.

The Stamp Act Congress had one intended goal, to remonstrate with Parliament about how the Stamp Act violated their rights as English citizens. On the 19th, the Congress produced a resolution called the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, a fourteen point list of the colonists positions, that was written by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania. Dickinson was a prominent Pennsylvania lawyer who would later rise to fame by writing a series of letters known as the "Farmer's Letters," in which he argued that various British acts violated the rights of the colonists. Dickinson would later serve in the First and Second Continental Congresses, and would write the Declaration and Resolves, a precursor to the Declaration of Independence, the Olive Branch Petition, Congress' last attempt at peace and the first draft of the Articles of Confederation, America's first governing document after the Revolutionary War.

In the Declaration of Rights and Grievances Dickinson enumerates "the most essential rights and liberties of the colonists, and... the grievances under which they labor, by reason of several late acts of Parliament." He states that the colonists are loyal to the King, that Parliament can not tax them legally since they are not represented in Parliament, that trying them in admiralty courts violates the English Constitution and that they have the full rights of Englishmen.

The Stamp Act Congress also produced a memorial to the House of Lords, a petition to the House of Commons and an address to King George III. The Congress forwarded copies of the Declaration of Rights and Grievances to all thirteen colonies, instructing them to adopt the resolutions as their own and send them to England. All thirteen colonies eventually issued public acceptances of the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, but only six of them followed the Congress' instructions to send copies to the King and to Parliament.

The Stamp Act Congress was significant because, with the exception of the Albany Congress, it was the first act of joint cooperation between the colonies and it issued the first official statement issued jointly by the colonies in opposition to an act of British rule. The Albany Congress met in 1754 at Albany, New York in order to discuss joint cooperation between the colonies in response to increased Indian aggression on the western frontier. Both Benjamin Franklin and Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson attended the Albany Congress and both agreed that a union should be established to deal with the Indians, but there was not enough agreement between all the delegates and no union was formed. The British looked back upon this precedent when considering the Stamp Act, falsely believing that the colonies had too many disparate interests to work cooperatively.

The Stamp Act Congress, though, was the first united colonial response to England. Later, as the Revolutionary War approached, the colonies would follow the same procedure of electing representatives to send to a continental congress. The later First Continental Congress also produced a list of grievances in the same manner as the Stamp Act Congress, called the Declaration and Resolves. The Second Continental Congress of course, produced the Declaration of Independence. It is important to recognize that these later congresses and declarations followed the example of the Stamp Act Congress.

The Board of Trade was quite alarmed when it learned about the impending Stamp Act Congress. The Board of Trade was a committee of members of the House of Lords that oversaw foreign trade and the colonies fell under their oversight. They were completely caught off guard by the violence that began to erupt. The fact that the colonies began to act in unison to challenge Parliament's authority was a strong warning sign of what was to come. The Board informed the King of the upcoming Congress shortly before it began, also sending him a copy of the Virginia Resolves, a set of resolutions adopted by the colony of Virginia protesting the Stamp Act. The Board thought Parliament ought to act on this immediately, but it was too late to stop the defiant colonists from meeting.

The Virginia Resolves

The strongest legislative statement and the one that had the most wide reaching impact came from Virginia. The Virginia House of Burgesses was meeting in October 1765. Patrick Henry, a young burgess serving his first term in the House, was frustrated with his more conservative elder colleagues. They did not intend to challenge the Stamp Act at all, even though many of them were personally against it.

On the evening of October 28th, Henry sat at Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg and wrote down seven resolutions against the Stamp Act on a napkin. The following day he gave a fiery speech to the House of Burgesses. He railed against Parliament for taking away their rights as British citizens and taxing them without authority to do so. He said the colonists had no obligation to pay this unjust tax. Henry even challenged the King, at one point making the following comment, as remembered by those who were present:

"Tarquin and Caesar had each his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell and George the third... (At this point Speaker John Robinson cried out, "Treason, treason!" and others in the house cried out, "Treason!" as well.) At this point, Henry paused and collected himself, continuing... "may profit by their example. If this be treason, make the most of it!"

At first it appeared that Henry was calling for the death of King George since the others he mentioned had all been executed. This is why the others began to cry out, "Treason!" Henry quickly saved himself from the situation though with his clever response. Thomas Jefferson, who was present, later said,

"I well remember the cry of treason, the pause of Mr. Henry at the name of George the Third and the presence of mind with which he closed his sentence, and baffled the charge vociferated."

These are the seven resolutions attributed to Henry and the Virginia House of Burgesses. Known as the Virginia Resolves, it should be noted that the first five were approved by the House, but the fifth one was repealed in a second vote the following day. All seven appeared in many newspapers at the time, as if Virginia had passed them all, but only the first four actually appeared in the Virginia Resolves. It is not known who created the last two, though some sources say they were in Henry's original notes:

- Resolved, that the first adventurers and settlers of His Majesty's colony and dominion of Virginia brought with them and transmitted to their posterity, and all other His Majesty's subjects since inhabiting in this His Majesty's said colony, all the liberties, privileges, franchises, and immunities that have at any time been held, enjoyed, and possessed by the people of Great Britain.

- Resolved, that by two royal charters, granted by King James I, the colonists aforesaid are declared entitled to all liberties, privileges, and immunities of denizens and natural subjects to all intents and purposes as if they had been abiding and born within the Realm of England.

- Resolved, that the taxation of the people by themselves, or by persons chosen by themselves to represent them, who can only know what taxes the people are able to bear, or the easiest method of raising them, and must themselves be affected by every tax laid on the people, is the only security against a burdensome taxation, and the distinguishing characteristic of British freedom, without which the ancient constitution cannot exist.

- Resolved, that His Majesty's liege people of this his most ancient and loyal colony have without interruption enjoyed the inestimable right of being governed by such laws, respecting their internal policy and taxation, as are derived from their own consent, with the approbation of their sovereign, or his substitute; and that the same has never been forfeited or yielded up, but has been constantly recognized by the kings and people of Great Britain.

- Resolved, therefor that the General Assembly of this Colony have the only and exclusive Right and Power to lay Taxes and Impositions upon the inhabitants of this Colony and that every Attempt to vest such Power in any person or persons whatsoever other than the General Assembly aforesaid has a manifest Tendency to destroy British as well as American Freedom.

- Resolved, That his majesty's liege people, the inhabitants of this colony, are not bound to yield obedience to any law or ordinance whatsoever designed to impose any taxation whatsoever upon them, other than the laws and ordinances of the general assembly aforesaid.

- Resolved, That any person who shall by speaking or writing maintain that any person or persons other than the general assembly of this colony have any right or power to impose or lay any taxation whatsoever on the people here shall be deemed an enemy to this his majesty's colony.

Mass Protests, Mob Violence and other resistance

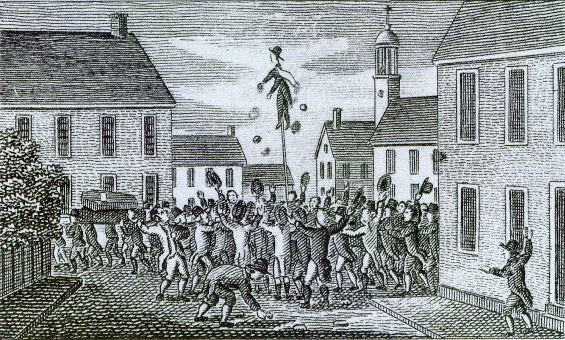

As it became clear that Parliament intended to enforce the Stamp Act, the colonists became more and more alarmed and many began to advocate physical resistance to officials who tried to enforce the act. Across the colonies, those who had been appointed stamp distributors, as well as tax and customs officials and royal governors came under attack. Their homes were destroyed and their lives were threatened. Some were marched into the streets at gunpoint and forced to sign statements that they would not have anything to do with selling stamps. Others were chased out of their homes and into neighboring colonies. Some fled their homes with their families to British warships in nearby rivers or harbors where they hoped to stay until the crisis simmered down.

The first act of mob strength occurred in Boston on August 14th when the crowd burned Andrew Oliver, Massachusetts' stamp distributor, in effigy. To burn someone "in effigy" means to make a model or a dummy of the person and then burn it. The next day Oliver was forced to resign. A few weeks later crowds looted and burned the homes of several tax and customs officials, including the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson.

Zachariah Hood, the stamp distributor for Maryland was burned in effigy and had his own warehouse burned down. He hid in Annapolis for a few days, but eventually fled to New York, allegedly in such haste to get away from the mobs in Maryland that his horse died underneath him! The New York Sons of Liberty captured Hood and threatened to return him to Maryland unless he would renounce his job as stamp distributor, which he finally did.

Citizens boarded a Royal Navy ship in Maryland looking for stamps that led to an incident between the ship's crew and local patriots, ending up with the crew jumping in the water and swimming for their lives. In Rhode Island, homes of government officials were ransacked and many of them fled to a British warship in the harbor at Newport.

In September, the home of Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia was attacked because it was believed that he supported the Stamp Act. Franklin was in London representing the colony. He had suggested his long time friend John Hughes be appointed stamp distributor in Pennsylvania. In reality, Franklin did not support the Act, but was trying to find ways to live with it because he thought its passage was inevitable. When the mob attacked, Franklin's wife stood inside her house with a pistol to protect herself, but she didn't end up needing to use it as hundreds of Franklin's friends and supporters came to her rescue and guarded the house.

In Georgia, Governor James Wright was confronted by the Savannah Sons of Liberty at his own front door. He answered with a pistol to protect himself. He had the stamps moved to a safer location and posted armed soldiers around the stamps and around his own house. For many nights he kept his clothes on anticipating that violence could arise against himself at any moment.

In South Carolina, 2,000 citizens gathered at Charleston to protest the arrival of the colony's stamps. They ransacked the homes of stamp distributors George Saxby and Caleb Lloyd. Lieutenant Governor William Bull hid the stamps in Fort Johnson. When the local Sons of Liberty found out where they were, they stormed the Fort and publicly burned all the stamps.

On November 1st, citizens of New York City confronted Governor Cadwallader Colden at Fort George. New York's stamps were being held at the Fort and Governor Colden had retreated there for his own safety. With cannons pointing down at the citizens, the mob confiscated Colden's carriage and marched it around the city, ending with a bonfire that destroyed the carriage and a gallows hanging an effigy of the governor.

One of the first acts of armed resistance by colonists against the British government took place at Wilmington, North Carolina on November 16th when the citizens confronted Governor William Tryon at his home. They demanded that he turn over to them William Houston, North Carolina's stamp distributor. At first Tryon refused, but when they started making preparations to burn his house down he relented and gave them Houston who had been hiding in his house. Houston was forced to publicly renounce his position as stamp distributor and sign a document saying he would not do anything to enforce the act. Read William Houston's resignation as Stamp Distributor from North Carolina here.

On November 28th, armed citizens lined up at Brunswick, North Carolina to prevent the sloop of war Diligence from unloading her cargo of stamps for the colony. Speaker of the Assembly, Colonel John Ashe informed Captain Phipps of the Diligence that anyone attempting to unload the stamps would be shot. In February, 1,000 armed citizens stormed the port at Brunswick again, along with the British warship Viper, demanding that two ships that had been confiscated for violating the Stamp Act be returned to their owners. Later, what may have been the first bloodshed of the American Revolution happened on the Viper when a dispute arose between two soldiers, one who agreed with the Americans on the tyranny of the Stamp Act and one who was related to Governor Tryon. This led to a duel in which one of the soldiers was killed.

On October 31, 1765, 200 prominent New York City merchants met and signed a non-importation agreement. They agreed they would not buy any goods from Great Britain starting on January 1, 1766, unless the Stamp Act was repealed. This precedent was followed in other localities around the colonies. It had a major impact because a huge proportion of British manufactured goods were sold to the colonies. Merchants in England immediately began to feel the impact and began to appeal to their Parliament members to repeal the act. Read the text of the New York non-importation agreement here.

The effect on many British manufacturers and financial institutions was so severe that they worried about paying their employees, receiving any money due them from the colonies and falling into complete financial ruin. On October 31, the Philadelphia Gazette published an anonymous letter received by a New York businessman from a London based merchant. In it, the merchant laments the difficulties the Stamp Act has caused, saying that his firm is owed 100,000 pounds that they worry they'll never get back. He says, "If this cursed Act is not repealed, we shall be great Sufferers and our Manufacturers thrown on their Parishes for want of support, whilst people who employed them will not be in a much better situation."

Repeal of the Stamp Act

Prime Minister Grenville fell out of favor and was replaced by Lord Rockingham on July 10, 1765. Rockingham was generally more favorable toward the colonists and was also a strong opponent of Grenville. News of the mob violence began to reach England by October of 1765. British merchants began to press Parliament to repeal the Act because of their hurting pocketbooks. The country was already in a deep economic depression. Now many colonial importers were refusing to do business with England. Bills were going unpaid. New orders were not being placed. A great deal of England's exports went to the colonies and the colonial non-importation agreements were having their effect.

It is estimated that the colonies owed $360 million to British merchants at the time the Stamp Act was passed. These merchants were highly dependent on the trade with the colonies continuing and prospering, but now it had come to a halt. Manufacturing cities across England were suffering with huge rates of unemployment as businesses had to let workers go because they had nothing for them to do. Some cities such as Bristol, Liverpool and Manchester may have had up to 100,000 workers laid off. Reports were coming in that the laid off workers would begin rioting and marching on London if something wasn't done soon.

On December 6, 1765 the Committee of Merchants in London delivered an address to the mayor of London stating that if Parliament did not repeal the Stamp Act soon many businesses would be forced to shut down and would lose their property. Prime Minister Rockingham and his assistant Edmund Burke, another member of Parliament, began organizing a committee of correspondence of their own, consisting of British merchants whose businesses were suffering as a result of the Stamp Act. These merchants began to lobby their members of Parliament, submitting a letter to the House of Commons on January 17th requesting a repeal. Other petitions to Parliament came in from towns large and small across Great Britain requesting a repeal. You can read the Letter from London merchants urging repeal of the Stamp Act here.

Other people in England wanted Parliament to take a strong stand against the colonists and enforce the Stamp Act. Some factions of Parliament were advocating sending the military to enforce the Act no matter how much blood was spilled in order not to set the precedent of Parliament bowing down to protest. The House of Commons asked King George III what he believed they should do. If they were to agree to the colonists' demands it would make the King and the Parliament look weak and encourage others to rebel against them also. If they didn't agree to the colonists' demands it would ruin the British economy. The King was in favor of amending the Act, but his advisors believed it had to be completely enforced or completely repealed. When Parliament met in December, Grenville, who was still a member of Parliament, though not Prime Minister anymore, submitted a proposal to condemn the colonies for their acts of violence. The members debated whether or not to send armed forces to America to enforce the Stamp Act, but the measure was defeated because many members realized the Act was a lost cause. If the British had decided at this time to enforce the Stamp Act militarily, the Revolutionary War would probably have happened ten years sooner.

On January 14, 1766, Parliament reconvened after Christmas and Lord Rockingham presented his plan for repeal. Some members suggested amending the Stamp Act instead, by allowing the colonists to pay the tax with their own printed money instead of in pounds sterling, but most saw this as too little too late. During the discussion, William Pitt made a famous speech in which he defended the colonists, agreeing that though Parliament was "sovereign and supreme, in every circumstance of government and legislature whatsoever," it was his "opinion that this Kingdom has no right to lay a tax upon the colonies." He also said that the colonies acknowledged the King's "authority in all things, with the sole exception that you shall not take their money out of their pockets without their consent." This speech electrified Parliament and made Pitt one of the great defenders of the colonists in England. You can read the speech, In Defense of the Colonies, by William Pitt here.

Lord Rockingham invited Benjamin Franklin, living in London as the representative of several colonies, to Parliament to inform them about colonial policies and attitudes. On February 13, Ben Franklin was interviewed by the Committee of the Whole of the House of Commons in order for them to better understand the American position. Franklin gave a masterful response. Edmund Burke later said it was like "an examination of a master, by a parcel of schoolboys." Franklin was interviewed by several members, including Lord Grenville, Charles Townshend, Lord North, Lord Thurlow, and Burke.

During the discussion, many of the questions focused on matters of trade, the ability of the colonies to manufacture goods, quantities of items traded and purchased from England, types and amounts of taxation in America and American views toward Parliament, taxation and the Stamp Act. Reading the entire discussion will give you a very good idea of the issues involved with the Stamp Act and also give an insightful look into the cleverness of Ben Franklin who performed masterfully before them. You can read the transcript of the Examination of Benjamin Franklin before the House of Commons here. Franklin's comments to Parliament made many members see that enforcing the Stamp Act in the colonies was going to be impossible without resorting to force.

Franklin had fallen out of favor with many colonists because he had earlier stated that the colonists would just have to accept the Stamp Act, even though they didn't like it, and for recommending his friend John Hughes for the position of stamp master in Pennsylvania. The colonists were so furious with him that they even attacked his home in Philadelphia, but friends of his confronted the mob and stopped them. Franklin's discussion before Parliament was probably one of the primary factors leading to the decision to repeal the Stamp Act and this restored him in the eyes of the colonists.

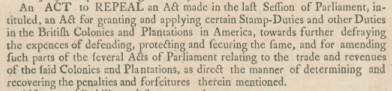

Lord Rockingham shifted the focus away from constitutional issues and began to focus on economic issues, presenting petitions from all over England asking for a repeal of the Stamp Act. Finally, on March 4, 1766, a vote was made in the House of Commons to repeal the act and it passed 276-168. On March 17, the House of Lords also voted for repeal. They immediately informed the King who came to Parliament the next day to sign the repeal into law. Read the Act Repealing the Stamp Act here.

When King George went to Parliament on March 18, 1766, there were so many people in the streets cheering, clapping hands and celebrating that it took the King several hours to get to the House of Lords. He called the Commons over to the House of Lords and signed the repeal in front of everyone. The news spread all over London immediately and celebrations broke out everywhere with ships displaying their colors, bonfires and illuminations in various parts of the city. Ships were immediately dispatched to the colonies to inform them of the repeal. Messengers were immediately sent to all the manufacturing towns of England.

You may ask, "Why was there such celebrating in England when the Stamp Act was repealed? Weren't they upset or humiliated that the colonists had won?" The answer is a big "NO!" A huge percentage of England's economy was dependent on trade with the colonies. Merchants weren't receiving payments for goods already shipped. Many were facing bankruptcy and closing down for good. Many people were losing their jobs as manufacturers suffered. The repealing of the Stamp Act meant that many people would go back to work, be able to pay their bills and get on with the business of making money again.

There were many members of Parliament who were alarmed that their backing down would make Parliament look weak and encourage more resistance in America. King George even said it "would ruin him, themselves and the nation, by trying for popularity." In other words, it would make them look weak and bring ruin on the nation if the government looked weak. They had to find a way for the government to save face and still be able to repeal the Act to save the merchants.

The remedy was the Declaratory Act, another act they passed at the same time as the Stamp Act repeal. The Declaratory Act stated that Parliament still had the legal right to tax in all issues whatsoever. It passed overwhelmingly, with only a few members voting against it. Lord Rockingham allowed the Declaratory Act to be voted on and passed even though he did not favor it himself, in order to get the members to pass the repeal.

The two acts together, the Stamp Act's repeal and the Declaratory Act became known as the "Twin Brothers." The Declaratory Act was a sign that the conflict between colonies and Parliament was far from over because, in spite of repealing the Stamp Act for expediency's sake, Parliament had not really changed its position. The fact that they maintained their view that it was lawful for them to tax the colonists became evident a year later with the passage of the Townshend Acts, another signpost on the road to the Revolutionary War.

Even though he signed the repeal, King George said the decision was a "fatal compliance which had wounded the majesty of England, and planted thorns under his pillow."

After the Stamp Act

The day after the Stamp Act was repealed, dozens of prominent London merchants met at King's Arms Tavern in Cornhill to write an address to the King expressing their pleasure at the repeal. More than fifty of them went in their coaches in a huge procession to Parliament to deliver the message to the King personally. They immediately dispatched ships that were already loaded and waiting in the river to go to America. Everyone was elated that business would resume as normal.

Word of the Stamp Act's repeal began to arrive in the colonies by mid May. Colonists everywhere celebrated the repeal. Celebrations took place in every town. Ships in the harbors were covered with flags. Bonfires burned everywhere. Colonial assemblies and town councils published letters of thanks to the King and to Parliament.

In Boston, the Sons of Liberty erected an illuminated obelisk with patriotic imagery and portraits of English politicians who had defended the colonists' cause. Paul Revere helped design the obelisk, which was a four sided tower made of paper over a wooden frame. Revere is known to have been involved because he produced a copper plate engraving of the obelisks on the night they were erected on Boston Common. Read more about the obelisk erected upon the repeal of the Stamp Act and view a larger picture.

The colonists were so thrilled, a statue of King George III riding a horse was erected on the Bowling Green in New York. Statues of William Pitt were raised at the corner of William and Wall Streets in New York and another one in Charleston, South Carolina.

In Maryland, celebrations were held in towns large and small. In Queen Anne Town, the prominent citizens met and buried the Stamp Act in a hole, toasting the repeal. The governor even proposed giving Zachariah Hood, the disgraced stamp master whose warehouse had been destroyed, 100 pounds to reimburse him for his loss. The citizens were glad to pay him.

Westmoreland County, Virginia, commissioned a painting of William Pitt by the famed artist Charles Willson Peale. British merchants cheered the repeal of the Stamp Act and promptly resumed their trade with the colonies. Newspapers in London printed cartoons making fun of Grenville's administration. One popular cartoon was called "The Funeral of Miss Ame-stamp," and depicted a funeral procession going to the tomb of the Stamp Act. The cartoon also depicted George Grenville carrying a child's coffin and labeled "Miss Ame-Stamp born 1765, died 1766."

In spite of the celebrations at the repeal of the Stamp Act, the colonists would not be celebrating long. Only a year later, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts to raise revenue for the salaries of judges and governors to rule the colonies apart from colonial rule. The acts led to the British occupation of Boston, the Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party and the Intolerable Acts on the road to the American Revolution.

Here is a detailed list of the purposes, provisions and results of the Stamp Act:

Purposes of the Stamp Act

- To raise revenue to help pay off the British national debt at the end of the French and Indian War.

- To raise revenue to help pay for the salaries of British soldiers stationed in the colonies after the end of the French and Indian War. 10,000 soldiers were stationed in the colonies, allegedly to protect them from Indian incursions along the frontier.

Provisions of the Stamp Act

- The Stamp Act placed a small tax on 54 commonly used items such as contracts, wills, newspapers, diplomas, certificates and many other items printed on paper.

- Stamped paper for these items had to be purchased from government authorized paper dealers. Anyone printing without the required stamp would be guilty of violating the law.

- The Stamp Act created admiralty courts for trying violators of the Act. The admiralty courts met in Nova Scotia, requiring an accused colonist to pay for a trip to Nova Scotia to defend himself.

- In the admiralty courts, decisions were made solely by the judge, without the benefit of a jury, upending centuries of precedent that allowed British citizens the right to trial by jury. Judges who found people guilty under the act were paid more than if they found the accused innocent.

- The act called for the creation of "ecclesiastical courts" for the trying of certain matters.

Results of the Stamp Act

- Colonists revolted against the Stamp Act across the colonies. They were upset that Britain intended to tax them for common everyday transactions such as wills, marriage certificates and newspapers, when they had never been taxed for such things before, and because of the threat of removing their right to trial by jury, a right of British citizens that had been established for centuries.

- Colonial legislatures passed acts condemning the Stamp Act.

- The colonies met in a joint congress to plan their joint opposition to the act at the Stamp Act Congress in New York City.

- Prominent citizens wrote widely circulated pamphlets and articles discussing the rights of British citizens, informing the public why the Stamp Act was a violation of the British Constitution.

- Mob violence against stamp distributors, governors and tax officials occurred across the colonies forcing all the stamp distributors to quit their jobs before the date the Act was to begin. Officials homes were ransacked and destroyed, their lives were threatened, stamps were captured and burned and armed colonists lined up on the shores to prevent stamps being unloaded from British warships.

- Colonial merchants formed non-importation agreements stating that they would not buy or sell British manufactured goods until the Stamp Act was repealed. This had a huge impact in Britain as manufacturing came to a halt, many people became unemployed and businesses faced bankruptcy. English businessmen began to call on Parliament to repeal the Act.

- As a result of all the pressure, the Stamp Act was finally repealed on March 18, 1766.

Here is a short video with a good summary of the causes and events of the Stamp Act crisis:

You can read the entire text of the Stamp Act of 1765 here.

Now that you've read about the Stamp Act, test your knowledge about it with our Stamp Act Crossword Puzzle.

- This article is one of a chronological series of articles that explain the causes of the Revolutionary War. Follow the links to read about the preceding and following events leading up to the American Revolution The series is not complete, but future articles are in progress.

Published 11/17/11

Revolutionary War and Beyond Home

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments