The Sugar Act -

April 5, 1764

The Sugar Act, also known as the American Revenue Act of 1764, was one of a series of causes leading up to the American Revolutionary War. The British government passed a series of acts over the course of thirty years or so that made the American colonists increasingly angry. The Molasses Act, the Sugar Act, the Currency Act, the Stamp Act and others caused the Americans to believe that Parliament intended to use them for profit only and not recognize their rights as British citizens. All of these events together led the colonists to revolt and form the United States of America. You can learn more about the history of the Sugar Act below.

Background of the Sugar Act of 1764

The Sugar Act of 1764, also known as the American Revenue Act or the American Duties Act, was a modification of the already existing Molasses Act which was passed in 1733 and renewed every five years afterwards. The Molasses Act was hated by the colonists because it placed a tax of six pence per gallon on molasses imported from any country outside the British Empire. Had this act ever been enforced it would have created havoc in the colonial economy because the distilling of rum, which is created from molasses, was one of the largest industries in the colonies.

The molasses tax was never fully enforced though and the colonists smuggled in foreign molasses anyway. You can read more about the Molasses Act here. The Sugar Act changed all this. The immediate cause for the change was the French and Indian War, which is also called The Seven Years War by the British. The British government racked up a huge debt during the war to protect the colonies from the encroaching French army and their Indian allies. In addition, the government of Prime Minister John Stuart, the Earl of Bute, decided to place ten thousand British troops in the colonies for their further defense. It cost an estimated 200,000 pounds to support them each year.

Creation of the Sugar Act

The Sugar Act was enacted on April 5, 1764, in order to help reduce the staggering national debt incurred during the French and Indian War and to help pay for the continued presence of British troops in the colonies to defend from any further attacks. The two main thrusts of the Act were to actually collect the taxes that had been in place, but skirted around for so long, and to force the colonists to trade with Britain and her colonies instead of foreign powers, in an effort to boost the ailing British economy.

In April 1763, George Grenville succeeded Lord Bute as Prime Minister and he set about creating a policy to reduce the national debt. Before the French and Indian War, which lasted from 1756 - 1763, the British national debt was only 72,000,000 pounds. By January 1763, the debt had skyrocketed to almost 130,000,000 pounds.

After the French and Indian War, Britain posted 10,000 soldiers in the colonies to protect them from further incursions by Indians or other foreign powers. Lord Grenville's Sugar Act sought to get the colonists to contribute to the costs of this defense, a proposition that wasn't necessarily disagreeable to the colonists, but it was the way in which he went about it that caused them great consternation. The colonists did not mind being taxed by their own elected colonial legislatures, but Parliament was taxing them and they had no representatives in Parliament. This is the origin of the revolutionary battle cry, taxation without representation.

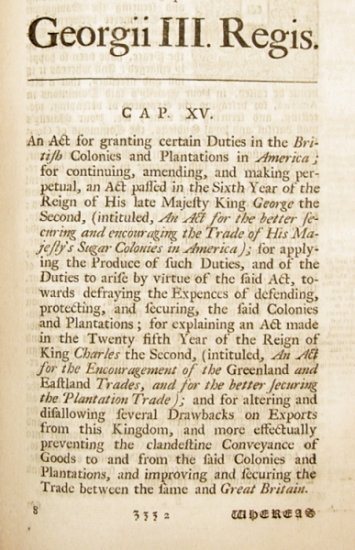

The Sugar Act marked the first time Parliament tried to directly tax the colonists. It was generally considered fair on both sides of the ocean for Parliament to regulate trade within the British Empire. Duties on imported goods were paid by shippers and were not a direct tax on consumption. The Sugar Act, however, was viewed as a direct tax on the consumption of many popular items including sugar, wine, textiles, tropical foods, silk and numerous other items, and had, as its stated purpose, the purpose of raising revenue for the Crown. This intent is stated clearly in the preamble of the Sugar Act:

"It is expedient that new provisions and regulations should be established for improving the revenue of this Kingdom... and... it is just and necessary that a revenue should be raised... for defraying the expenses of defending, protecting, and securing the same."

You can read the entire Sugar Act text here.

This angered the colonists because it seemed that Parliament wanted to use them for its own good. It may seem reasonable to expect that the colonists would be partly responsible for the expenses of their own defense. The colonists were not opposed to this. However, Parliament placed this tax directly on them, which violated the British political principle that taxes could only be levied if they were agreed upon by the common people through their elected representatives. The colonists had no elected representatives in Parliament and had been taxed only by their own colonial legislatures for over a hundred years. Thus the root of the conflict was whether or not Parliament had the right to tax the colonists.

In addition to the right of taxation question, colonists were angered and alarmed because the newly enforced taxes caused great economic hardship by raising the prices of many common goods, reducing foreign markets to which they could export their goods and creating burdensome trade regulations.

Provisions of the Sugar Act

The Sugar Act consisted of several main priorities. It sought to enforce the collection of the molasses and sugar taxes. This greatly angered the colonists because they had become accustomed to decades of evading this tax and, even though the Sugar Act actually lowered the tax to three pence per gallon from six, they still didn't want to pay any tax on it. Colonists were used to paying only a penny and a half per gallon bribe to customs agents to allow them to smuggle in untaxed molasses. So the tax, though lower, was still more expensive than smuggling.

The British Navy was given strict orders to enforce collection of the tax and to capture and prosecute anyone trying to evade it. Smugglers found it much harder to evade the authorities and, since a large part of the colonial economy was built on smuggled molasses, the colonial economy fell into a shambles. The widespread smuggling of molasses actually continued until 1766 when the tax was lowered to 1 penny per gallon, lower than the cost of bribing customs officials.

Colonial Shipping

Colonial ShippingThe Sugar Act also created a new and stringent system for importers and exporters to comply with. They had to follow a strict set of guidelines in their shipping procedures and written records, which made shipping much more difficult. The British were trying to get control over the shipping industry and reduce smuggling in order to increase the tax revenue. If captains didn't adhere completely with these complicated regulations, even in the smallest technicality, they risked having their entire cargo confiscated.

The Sugar Act also created a new system for the trial of those accused of evading the law and the taxes it created. In the past, colonists had been tried by a jury of their peers, as is done today, if they were accused of violating the law. The Act called for any such violators to be tried in the Admiralty Court in Nova Scotia. This was hundreds of miles away from the colonists and removed the possibility of being tried by their peers.

The British did this specifically to end jury trials because local juries were almost always sympathetic with smugglers and hardly ever convicted them. The system was also stacked against the accused colonist because it awarded the judge 5% of the worth of the cargo if the defendant was found guilty. Finally, colonists had to actually pay their own expense to travel hundreds of miles to Nova Scotia to defend themselves!

Parliament wanted to collect the tax to reduce the national debt, but also to boost the British economy. The reasoning was that colonists would buy more British produced molasses and sugar products because foreign made molasses and sugar products would become more expensive, but in fact, the Sugar Act had the opposite effect and ended up hurting the British economy.

The Sugar Act was implemented at a time of economic depression in the colonies. Much of the colonial economy during the previous decade had revolved around supplying British troops with food and supplies during the French and Indian War. Now that the war was over, many merchants found themselves struggling financially. The Act made the problem worse by restricting trade with foreign markets. Colonial agricultural goods such as lumber, fish, cheese and flour were sold to French West Indian islands such as Martinique, Guadalupe and Santo Domingo (Haiti) and to the Azores, Canary Islands and Madeira (in Portugal). These items were purchased with money gained from the sale of molasses, other sugar products and wines.

The tax on molasses and wine from countries outside the British empire made them so expensive that colonists could no longer purchase them from these islands. This caused the islands to have less money with which to buy colonial agricultural and other products, causing a widespread economic depression. Of course this made the colonists extremely angry with Parliament because the price of common goods such as sugar, molasses and wine skyrocketed and colonial exports plummeted. In addition, Parliament hurt British manufacturers as well because the colonists now had less money with which to buy British made goods!

Parliament intended to boost the British economy by making foreign produced goods more expensive, which would cause the colonists to buy more British made goods and produce. The Sugar Act also required that many items be shipped through British ports. Parliament reasoned that shippers would be more likely to buy British made products if they were required to pass through British ports. In actuality, all of this hurt the British economy and caused widespread economic difficulties by decimating the colonies' number one industry - the production of rum, reducing the colonists ability to sell their own produce to foreign markets and reducing the amount of money the colonists had to purchase British made goods.

Colonial Response to the Sugar Act

Samuel Adams

Samuel AdamsThe passage of the Sugar Act marked the first organizing of colonists and public protests against the British Parliament. There were sporadic outbursts of violence against the authorities, especially in New York and Rhode Island. Certain leaders began to arise who were outspoken in their criticism of parliament, especially Samuel Adams and James Otis of Boston. They led the way in organizing a boycott of British luxury items by many merchants in Boston. 50 merchants joined the boycott. A movement also began, especially in New York and Boston, to encourage manufacturing within the colonies themselves. Colonists felt that if they made their own goods, especially goods made from cloth such as linens, clothing, hats, etc., they would not be so dependent on British made goods.

The Boston Town Meeting, the ruling council of the city, discussed the Sugar Act and the impending Stamp Act and issued a letter to its representatives in the Massachusetts Colonial Legislature, instructing them to affirm and defend their rights as British citizens, which, they believed, were being infringed upon by Parliament. Samuel Adams was appointed by the town meeting to draft the letter to the legislature. This letter helped cement him as a leader in the protests against Great Britain. The letter marks the first time that a political body in the colonies declared that Parliament could not constitutionally tax the colonists. You can read the letter here, Instructions to Boston's Representatives, May 28, 1764.

James Otis

James OtisAnother rising leader to challenge Parliament's authority was lawyer James Otis of Boston. Otis published "Rights of the Colonies Asserted and Proved", a pamphlet which argued that Parliament had no legal right to tax the colonists. This was one of the first published and widely circulated colonial papers challenging Parliament. You can read Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved here.

In all, eleven provincial legislatures eventually sent formal complaints about the Sugar Act and the forthcoming Stamp Act to Parliament, eloquently stating their belief that Parliament did not have the

authority to directly tax them.

You can read the formal complaints from New York, Massachusetts and Virginia here:

- New York Petition to the House of Commons, October 18, 1764

- Massachusetts Petition to the House of Commons, November 3, 1764

- Virginia Petition of the House of Burgesses to the House of Commons, December 18, 1764

These complaints were mild compared to the fury that would arise with the soon to be enacted Stamp Act, but the anger caused by the Molasses Act, the Sugar Act and the Currency Act resulted in the widespread rebellion that occurred at the imposition of the Stamp Act the following year.

The Sugar Act was finally repealed in 1766 and replaced with the Revenue Act of 1766, which reduced the tax on imported molasses to one penny per gallon, whether British or foreign made. This occurred around the same time that the Stamp Act was repealed.

Here is a detailed list of the purposes, provisions and results of the Sugar Act:

Purposes of the Sugar Act

- To help cover the expenses of posting British soldiers in North America for the colonies' defense.

- To help reduce the British national debt, which had skyrocketed during the French and Indian War, which had been fought to protect the colonists.

- To reduce the huge smuggling trade and increase tax revenue for the Crown.

Provisions of the Sugar Act

- New taxes were imposed on sugar, wines, textiles, including cambric and calico, pimento, silk, tropical fruits, dyes and coffee. Molasses was taxed as well, but the rate was cut in half from the previous Molasses Act.

- Collection of the taxes was to be strictly enforced. Lord Grenville ordered the British Navy to strictly enforce the new tax and shipping regulations.

- Many items, including lumber could only be exported to Great Britain.

- Captains were required to make detailed lists of their cargo, which were subject to verification by customs officials. No cargo could be unloaded until the lists were verified.

- Anyone accused of violating the Sugar Act was to be tried in the Vice Admiralty Court in Nova Scotia, far away from local juries who were sympathetic to local smugglers.

- Judges were given 5% of the cargo's worth if they found the accused person guilty.

- Defendants were required to prove their innocence if accused of violating the Sugar Act, instead of being presumed innocent unless proven guilty.

- Many items, including iron, whalebone, lumber and furs could be exported to foreign countries if they passed through a British port first. Parliament reasoned that this would cause shippers to be more likely to buy British goods to take back with them to the colonies.

Results of the Sugar Act

- The enforcement of the molasses tax caused an immediate decline in the rum industry in the colonies, the largest industry in the colonies at the time.

- Enforcement of the molasses tax exacerbated the already existing economic depression. Trade with the Azores, Madeira, the Canary Islands and the French West Indian islands of Martinique, Guadalupe and Santo Domingo, which we call Haiti today, was greatly reduced because colonists were taxed too heavily to purchase molasses and other products from these islands. This caused these islands to be able to purchase fewer colonial goods such as cheese, lumber, flour and other agricultural products, depressing the economic activity of all sides.

- British manufacturers were hurt because the colonists had less money with which to buy British made products.

- Trade with foreign powers had been the main source of hard currency in the colonies. The Sugar Act reduced this trade so much that the stability of colonial currencies was threatened and the colonies had less hard currency with which to purchase British made goods.

- Colonists protested in various places. There were sporadic outbursts of violence against the British authorities. Boston merchants, led by Samuel Adams and James Otis, agreed to stop purchasing British made luxury products. Movements began in Boston and New York to encourage manufacturing within the colonies in order to reduce dependence on British made goods. These men and others began to rise to the forefront as opposition leaders against the acts of the British government.

- New smuggling industries were created where none had existed before. For example, colonists began to smuggle imported wine from Madeira, Portugal, an item which was not taxed before.

You can read the entire text of the Sugar Act here.

- This article is one of a chronological series of articles that explain the causes of the Revolutionary War. Follow the links to read about the preceding and following events leading up to the American Revolution.

<< Proclamation of 1763 Previous article Next article Currency Act >>

Last Updated 2/27/12

Revolutionary War and Beyond Home

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments