The Olive Branch Petition

What is the Olive Branch Petition and how did it come about? Many Americans did not want to break away forever from Great Britain. Many were angry with British policies and treatment, but they thought an agreement could somehow be reached with the King that would right the wrongs done to them. Declaring independence was a hope of some of the patriots, but not of most. Even when the Second Continental Congress met for the first time in May 1775, the majority was not yet ready to declare independence.

There was a small group of delegates, including John Adams, who were ready to declare independence at this time, but the more moderate voices prevailed. The moderate faction was led by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, probably the most conservative and loyal member of Congress. The radical faction decided it was wiser at this time to let the moderates have their way because they believed war with Britain was inevitable. They would wait until events persuaded more moderates to join their side.

The Congress decided to send a last appeal to King George III asking him to intervene in their behalf. The First Continental Congress and many of the individual colonies had sent numerous appeals to the Parliament and to the King, none of which had persuaded them to change their treatment of the Americans. Still hoping that they could avoid the Revolutionary War, they sent one last letter to the King.

The Americans hoped that King George III was not fully aware of how Parliament had been treating the Americans. So they sent the letter directly to the King, detailing the abuses they had received from Parliament and from local British officials. They couched their letter in terms that placed all the guilt with Parliament and British officials such as the Royal Governors. They did this so as not to offend the king and in hopes that he, being unaware of the treatment, would come to their defense.

The Olive Branch Petition

On June 3rd, 1775, Congress passed a resolution forming a committee to draft a letter to the King. The members of this committee were Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Johnson, John Rutledge, John Jay and William Livingston. This committee presented its letter to the Committee of the Whole (the whole Congress) on June 24, but it was not approved. Instead, on July 6th Congress reconsidered the matter and sent the committee back to form another proposal, adding John Dickinson and Thomas Jefferson to the committee.

Thomas Jefferson wrote the first draft, but John Dickinson, especially, thought the draft was too harsh and would only anger the king. So he was given permission to make alterations to Jefferson's draft. On July 8th Dickinson's version was presented to Congress and approved, but not unanimously. This letter has come to be known as the Olive Branch Petition, because it extended an offer of reconciliation to the King. The Olive Branch is of course a symbol of peace. It has also been called the "Humble Petition" and the "Second Petition to the King."

The letter affirmed the loyalty of the colonists to the King and assured him that they did not seek independence, only redress of their grievances. Congress' vote in support of Dickinson's draft, which was much more fawning in its tone toward the king, showed Congress' willingness to give those who held Dickinson's views one last chance at reconciliation, though they generally didn't believe it would work.

Read the text of the Olive Branch Petition here.

The Olive Branch Petition was signed by 48 members of Congress and entrusted to Richard Penn of Pennsylvania, a descendant of William Penn, the founder of the colony. Penn left America on July 14th and arrived in London on August 14th. He delivered the letter to Arthur Lee, who was the Agent in England for the Massachusetts Colony.

King George's Response

to the Olive Branch Petition

On August 21st, Penn and Lee presented a copy of the letter to Lord Dartmouth, who was the Secretary of State for the American colonies. Lord Dartmouth tried to present the letter to the King, but he would not receive it.

The day Congress approved the Olive Branch Petition, July 8, John Adams wrote two letters in disgust, one to his wife, Abigail, and the other to General James Warren. The letter to General Warren in particular expressed his disapproval of the petition and revealed certain war preparations. The letter was also very critical of John Dickinson. Both letters were intercepted by the British and published publicly, so when the King and Parliament were presented with the Olive Branch Petition, they didn't really take it seriously because the Americans were still preparing for war in spite of their letter.

Read John Adams' intercepted letter to James Warren here.

Read John Adams' intercepted letter to Abigail Adams here.

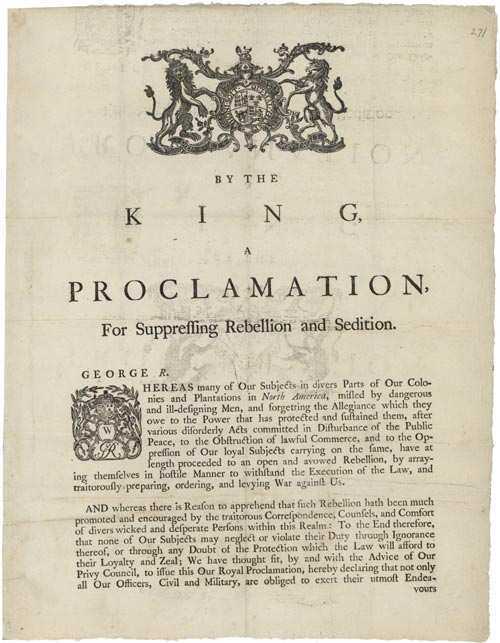

On August 23, the King published a proclamation declaring the colonies in America were in a state of full-scale rebellion. The proclamation also required that all British subjects anywhere were to assist in putting down the rebellion. This made it an act of treason for any British subject to defend the American cause in any way. Read King George's Rebellion Proclamation here.

On September 1st, Richard Penn and Arthur Lee went back to Lord Dartmouth to see if there was a response from the King. He informed them that the King would not even receive their petition. On September 2nd, Penn and Lee sent this short message to the Continental Congress:

"On the 21st of last month, we sent to the Secretary of State for America, a copy of the Petition from the general Congress; and yesterday, the first moment that was permitted us, we presented to him the Original, which his lordship promised to deliver to his Majesty.

We thought it our duty to press his Lordship to obtain an answer; but we were told that his Majesty did not receive it on the throne, no answer would be given.

your most faithful Servants

Richard Penn

Arthur Lee"

On November 7th, the Olive Branch Petition was presented to the House of Commons and a motion was made that they consider this petition the basis for an effort at reconciliation. The motion was defeated 83-33.

The Americans' Response

The Congress in Philadelphia received the message from Penn and Lee on November 9th, 1775, informing them that the King would not receive their petition of peace. This was a strong blow to those such as John Dickinson who hoped to avoid war. The radicals began to gain power now as word of the King's rejection of the peace offer began to spread. Many colonists who had hoped for a reconciliation now knew that it was impossible.

After hearing of the King's rejection of the Olive Branch Petition, many colonists were furious. Abigail Adams, the wife of John Adams, wrote this to her husband after hearing of the refusal, "Let us separate, they are unworthy to be our Brethren. Let us renounce them and instead of supplications as formerly for their prosperity and happiness, Let us beseech the almighty to blast their councils and bring to nought all their devices." Her view accurately reflected the opinions of many at the time. Read Abigail's complete letter to John written on November 12, 1775 here.

The colonists began to see the King as openly hostile to them. He was abridging their rights, making various rulings affecting them without their consent, amassing armies against them and refusing to even receive their petitions. The next spring, Thomas Paine published his pamphlet called Common Sense, which outlined the King's abuses and stated outright that the colonists had a right to throw off British rule because of its tyrannical ways. Common Sense convinced many colonists that independence and a Revolutionary War were justified. All of these events set the stage for the Declaration of Independence which would be declared in July 1776, only a few months later.

Read Thomas Paine's Common Sense here.

You can also read our Thomas Paine Quotes here.

One Last Try

A little known fact is that, in spite of the King's refusal to receive the Olive Branch Petition, the Congress actually sent one more letter to the King. On December 4th the Congress approved a response to the King's proclamation of August 23rd. In it they reasserted their loyalty to the king, their wish to avoid war and their belief that it was the king's ministers and not the king himself who were violating their rights. They published this letter and had it sent to their agents in Great Britain, but of course it accomplished nothing.

Instead, the King and Parliament rewarded the colonists with another act on December 23 that would close all commerce to the colonies starting on March 1, 1776. You can read this last congressional response to the King here.

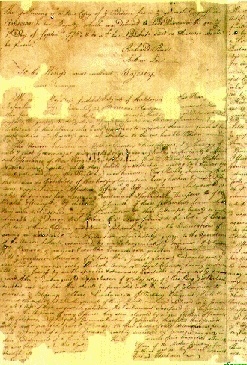

Copies of the Olive Branch Petition

There are two known copies of the original Olive Branch Petition signed by the Congressional delegates. One is held by the New York Public Library and the other is in the Public Record Office of London. In addition, a working copy exists that is held in the Karpeles Manuscript Library in Santa Barbara, California, along with the original report sent by Penn and Lee about the King's response.

You may also like to read these other articles about the Founding Fathers and the Declaration of Independence:

- Main Declaration of Independence page

- Learn more about the Purpose of the Declaration of Independence here

- Look at the Declaration of Independence in pictures

- Learn about Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence here

- You can view all the signatures on the Declaration of Independence as well

- Read about the History of the Declaration here

- Learn more about the Founding Fathers of America here

Last updated 8/10/12

Revolutionary War and Beyond Home

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments