History of the Bill of Rights

The History of the Bill of Rights is one aspect of American history that many people know little about. The Bill of Rights is one of the main founding documents of the United States of America. It consists of Ten Amendments to the United States Constitution. These amendments were added to protect basic God given rights from government interference. James Madison is credited with being the main author of the Bill of Rights. The Bill of Rights protects Americans' rights such as freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of the press, the right to have a trial by jury, the right to not incriminate oneself (pleading the fifth) and many other rights. This section will give you a good understanding of the events surrounding the history of the Bill of Rights.

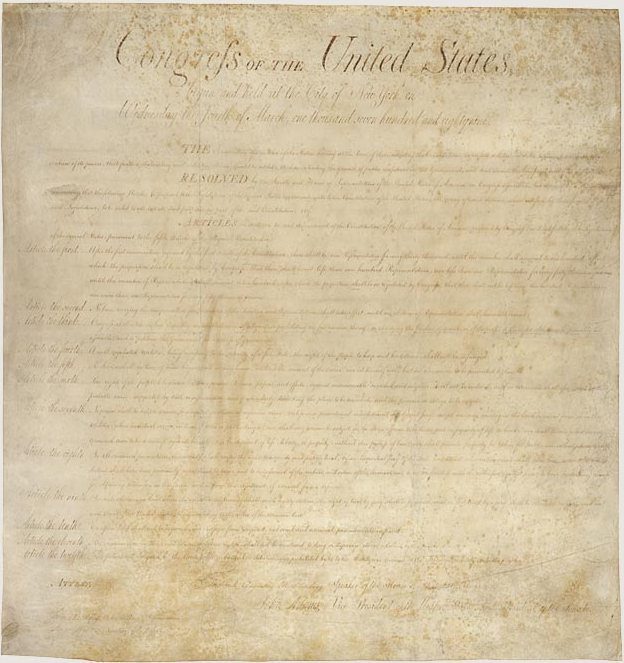

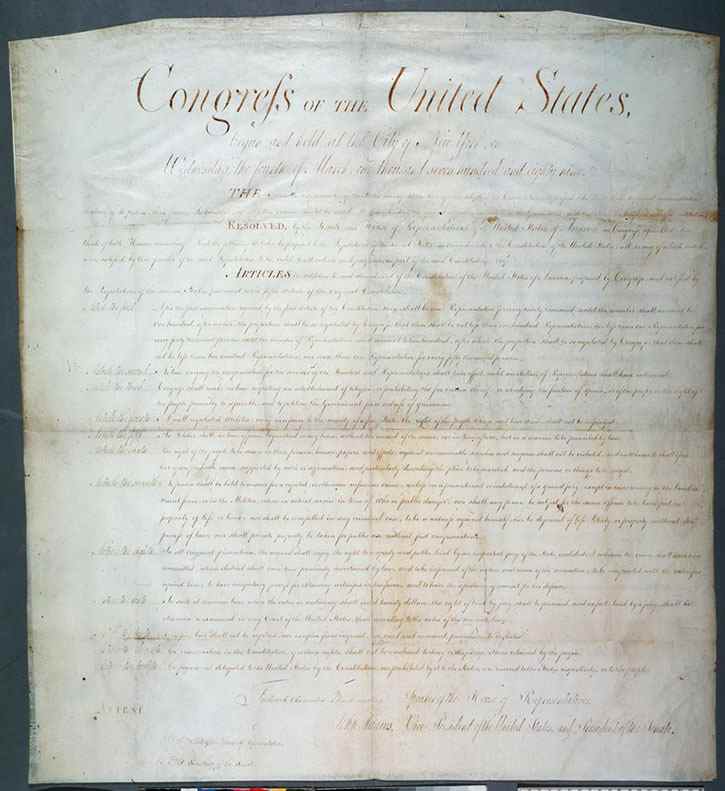

Bill of Rights

Bill of RightsHistory of the Bill of Rights

On June 7, 1776 Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented to the Second Continental Congress what became known as the Lee Resolution. The Lee Resolution proposed three things to the Congress at the direction of the Virginia Convention. The three things were 1) a Declaration of Independence from Great Britain, 2) that alliances with foreign powers against Britain should be sought out and 3) that provision should be made for a formal confederation between the thirteen colonies. Committees were set up to study each issue and to present ideas to Congress about how to implement them.

The committee set up to study the confederation proposed a draft in the summer of 1777 and the formal Articles of Confederation were adopted by the congress on November 15, 1777. The Articles still had to be ratified though by each colony. The last state to ratify was Maryland on March 1, 1781, and from that time the Articles of Confederation were the ruling document of the United States of America until the Constitution of the United States was adopted in 1788. Read the Articles of Confederation here.

History of the Bill of Rights -

The Articles of Confederation

Right from the start there were problems with the Articles of Confederation. Recall that the American people were extremely concerned about their government abusing their rights. This was the whole purpose of the Revolutionary War. Because of this fear, the Congress and colonies that adopted the Articles of Confederation made the government purposefully weak. The problem was that they made the government so weak that it didn't have enough power to accomplish much. Several issues that arose over the next few years included:

- The Congress had no power to tax the people to raise revenue. It could only ask the states for money or get loans. When it did ask the states for money, it had no power to force them to comply, so most of the time the states didn't send the requested money, yet the Congress was supposed to oversee military affairs and regulate the economy.

- Another problem was that each state had one vote. This was inherently unfair to the larger states because they were asked to contribute more because of their size, yet had no greater say in how things should be done.

- Congress was supposed to control the military, but had no power to impose taxes to pay for it. It also had no power to require people to serve in the army. Instead Congress would send requests to each state to supply troops, which many times went unfulfilled. This is one of the reasons why George Washington's Continental Army was continually undermanned.

- The Congress had no authority to require delegates to even meet. States would appoint their delegates, but they might or might not show up to scheduled meetings. This made the course of conducting business extremely slow. It was so slow that the Peace Treaty with Great Britain, which had already been signed by the ambassadors, sat for months in Congress because there weren't enough delegates present to vote on it!

- Congress could make decisions, but could not enforce them.

- Congress could not regulate trade between the states. Instead, each state created its own trade laws, rules and tariffs. This created a confusing set of regulations from state to state and created a great deal of competition from state to state in trade matters.

- Each state was considered to be a completely sovereign entity that could do whatever it wished apart from the specific things mentioned in the Articles which were given to the federal government, which included the right to make war, control foreign diplomacy, control weights and measure and act as an arbiter between states.

- Decisions had to be made unanimously, so one state could veto a measure that all the other twelve wanted.

History of the Bill of Rights -

Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists

All of these problems made many believe that the union could not ultimately be held together without doing something to strengthen the central government. These people were called "Federalists," because of their support for a strong central, or federal, government. The first two Presidents of the United States, George Washington and John Adams, were Federalists. The third, Thomas Jefferson, was an Anti-Federalist. Anti-federalists generally wanted the central government to be weaker so it did not encroach on the rights of individuals to govern themselves. You can't understand the history of the Bill of Rights without understanding the differences between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists.

The Virginia Plan

The Virginia PlanBy 1787, the states were convinced that the Articles of Confederation needed to be revised and the Congressional delegates met in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17 to try to make the necessary changes. Many present, including James Madison and Alexander Hamilton believed that the Articles were wholly insufficient and needed to be done away with completely. Consequently, what became known as the Virginia Plan, was presented to the Congress by Edmund Randolph, a Virginia delegate. Largely written by James Madison, the Virginia Plan, called for a completely new government and constitution with a much stronger central government. The picture at the right is James Madison's own copy of the Virginia Plan.

After much deliberation, the Congress voted to accept the new constitution on September 17, 1787. In order for the Constitution to take effect though it had to be ratified or accepted by 9 of the 13 colonies. This is when a very strong cry for a Bill of Rights occurred.

History of the Bill of Rights -

What is a Bill of Rights?

You can't understand the history of the Bill of Rights if you don't know what a Bill of Rights is! A Bill of Rights is basically a list of the rights of the people from which the government is forbidden from interfering. Bills of Rights were nothing new at this point in history. The Magna Carta, signed in 1215, forced King John to respect certain rights of those in his kingdom, such as their right to writs of habeas corpus (meaning their right to appeal unlawful imprisonment), and forced him to admit that his actions must be controlled by the law. The English Bill of Rights of 1689 guaranteed certain rights to the people as represented by their members of Parliament against the King, such as freedom to petition the government, freedom from taxation without legislative approval and freedom from cruel and unusual punishment. Many of the states had enacted their own bills of rights to protect their own citizens as well.

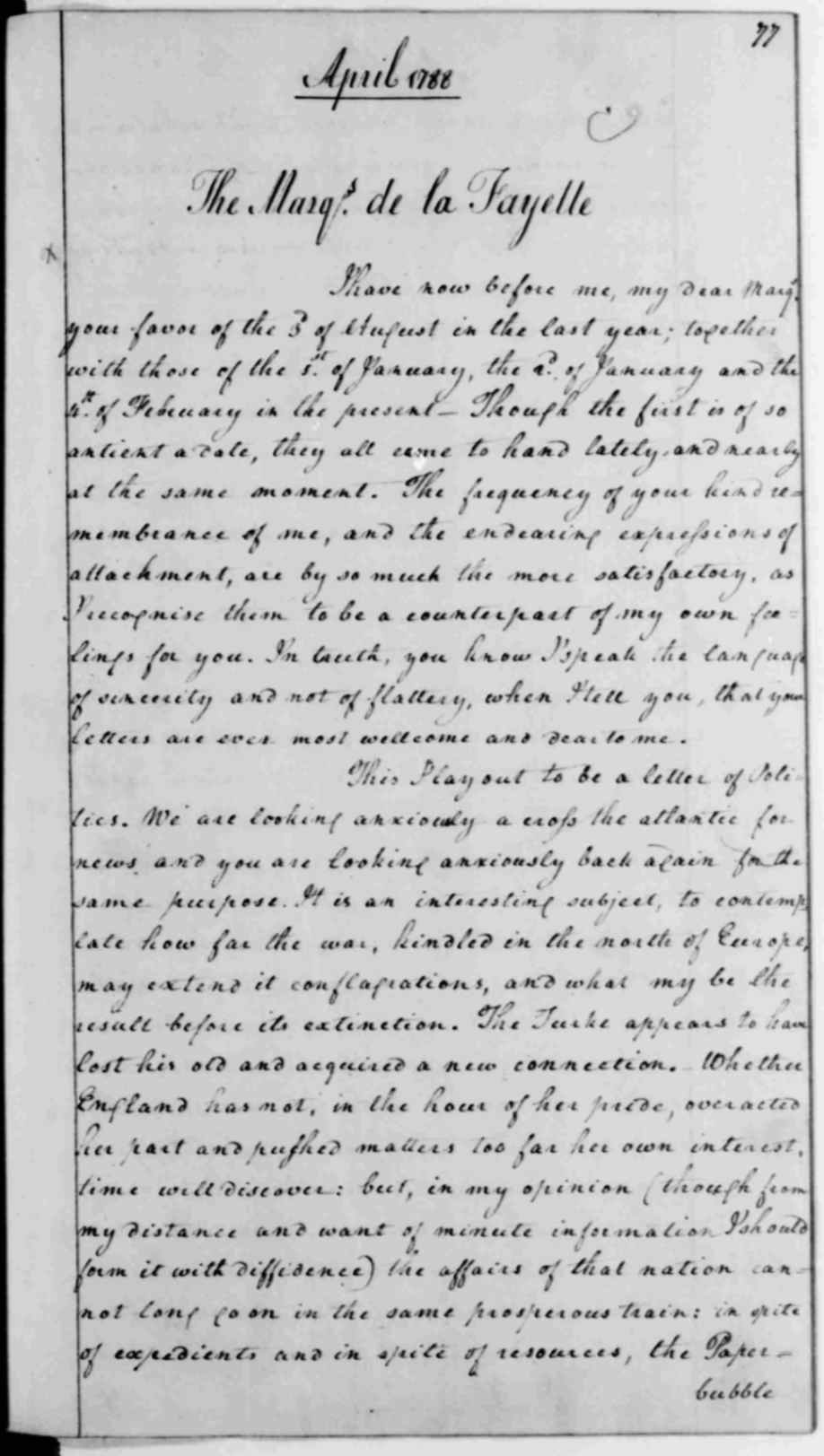

George Washington's Letter

George Washington's LetterAfter the states received their copies of the proposed Constitution, each state was to hold a ratifying convention to discuss the merits of the Constitution and to accept or reject it. Five states, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia and Connecticut, voted to ratify immediately. The rest of the states, however, were more slow to get on board. A vigorous and bitter public debate began all over the states between Federalists and Anti-Federalists about whether or not the newly proposed Constitution gave too much power to the government and did too little to protect the rights of individuals. Keep in mind, they had just fought a bloody war in order to get rid of an oppressive government. They sure didn't want to create another one! About this time, George Washington wrote to the Marquis de Lafayette, a French general who had helped him in the Revolutionary War. In his letter he talks about the proposed Constitution and the calls for a Bill of Rights. You can read the George Washington letter here.

Anti-Federalists, such as George Mason of Virginia, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts called for rejection of the Constitution completely or at the least, an inclusion of a Bill of Rights. George Mason had even proposed a Bill of Rights to the Constitutional Convention on September 12, 1787, according to James Madison's notes, but it was declined.

Federalists believed a Bill of Rights was unnecessary because they believed that the Constitution only gave the government limited powers that were specifically listed. The government had no power to do things it was not entitled to in the Constitution. Alexander Hamilton believed that the people were not giving up any rights by accepting the Constitution. Therefore, in his view, it was not necessary to protect something which was not taken away from them with a Bill of Rights.

The Federalists also believed, though, that adding a Bill of Rights could be very dangerous. If specific rights to be retained by the people were listed in the Constitution, they believed it would imply that any rights not listed were not protected and that the government would gradually encroach upon these rights.

The Anti-Federalists remained unpersuaded. They wanted guarantees for such things as freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom to petition the government and many others, specifically listed in the Constitution.

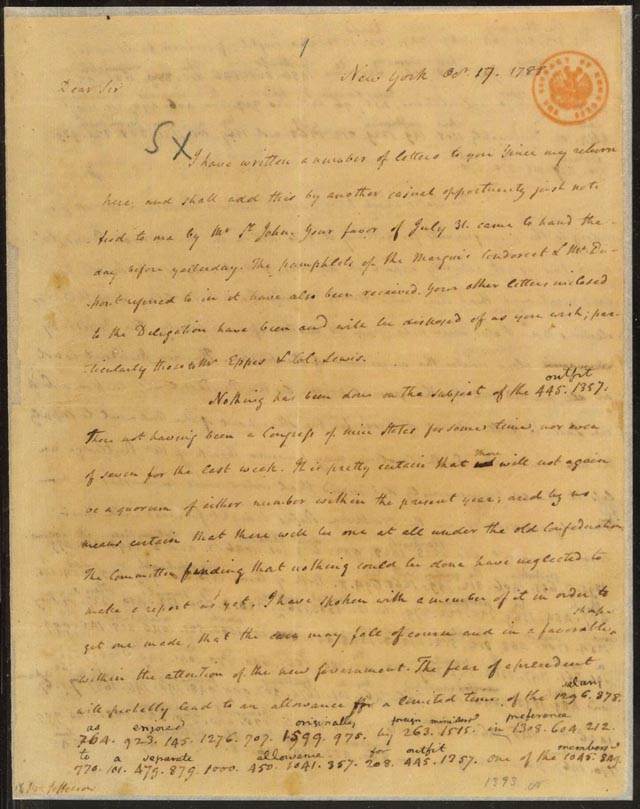

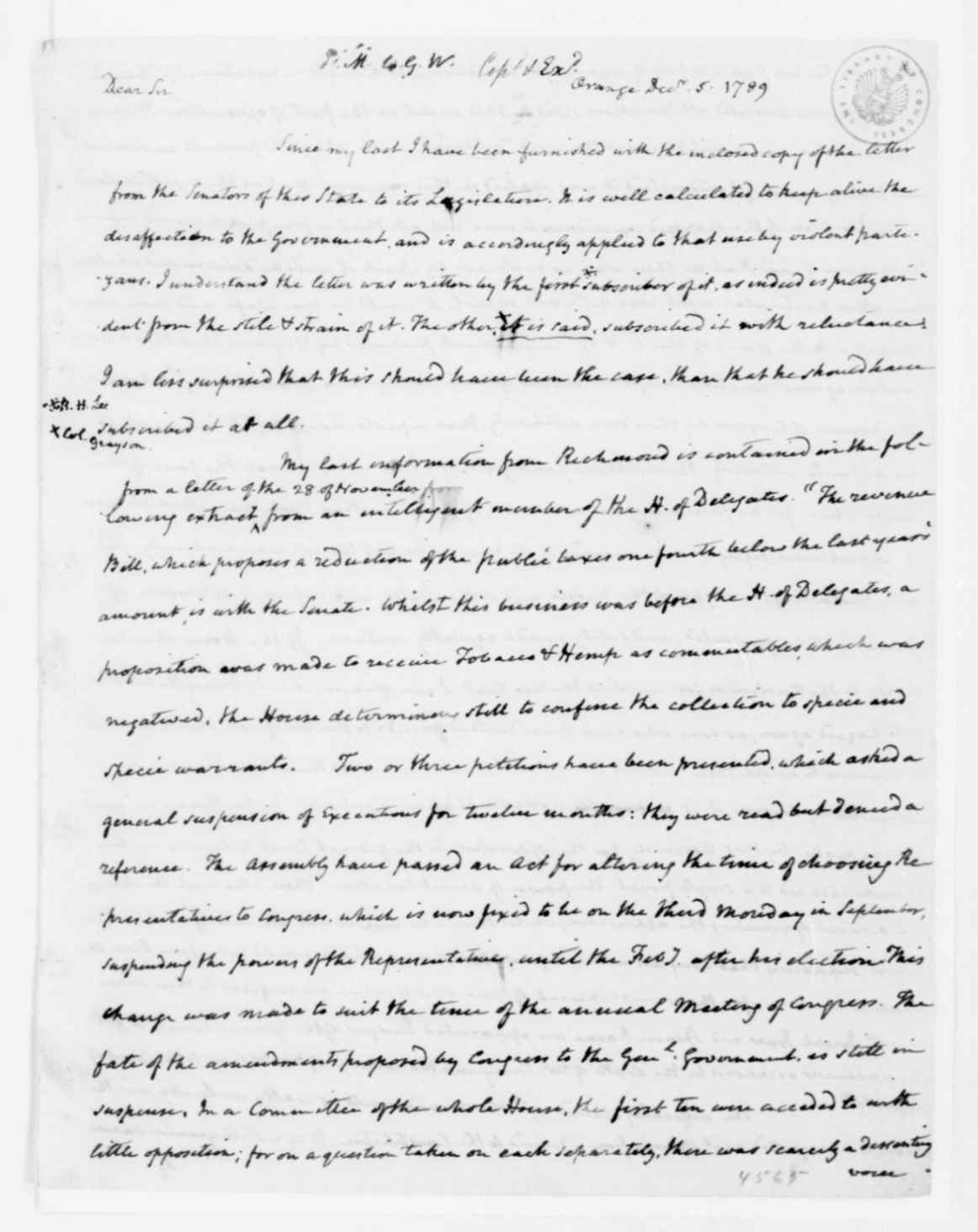

James Madison Letter

James Madison LetterThe impasse was finally overcome by what is known as the Massachusetts Compromise. The Massachusetts ratifying convention finally got enough Anti-Federalists on board by recommending a number of amendments be adopted by the First Congress under the new constitution. So the Anti-Federalists voted yes, on the promise that a Bill of Rights would be added. Four of the next five states to ratify did so with similar demands. North Carolina refused to ratify until significant steps had been made toward a Bill of Rights. James Madison wrote an interesting letter to Thomas Jefferson about this time, about the pros and cons of adding a Bill of Rights to the Constitution. Much of it was written in cipher, a secret code between the two parties that only they knew, so that if the letter was read by anyone else they wouldn't understand what was written. You can read the James Madison letter here.

History of the Bill of Rights -

Ratifying the Constitution

History of the Bill of Rights -

The First Congress

The first Congress under the new Constitution was scheduled to meet in March of 1789. The states had submitted over 200 proposals for amendments to be included in the Bill of Rights. Many people were even calling for another Constitutional Convention because they were displeased with the current one.

James Madison recognized that the new government would not succeed unless the states' demand for a Bill of Rights was not met. He personally did not believe a Bill of Rights was necessary. He agreed with Alexander Hamilton that the Constitution did not take any rights from the people in the first place. He also thought the State governments were more likely to pass unjust laws than the federal government, and he supported a provision that would have given the federal government veto power over all state laws.

James Madison

James MadisonMadison realized, however, that in order for the new government to be accepted, a Bill of Rights would be necessary. He ran into the same Anti-Federalist sentiment that existed in the Massachusetts Constitutional Ratification Convention, when he was trying to get the Virginia Ratification Convention to accept the new constitution. He ended up publicly supporting the addition of amendments in order to help get it ratified. He basically considered passing a Bill of Rights to be throwing a bone to the Anti-Federalists in order to get their support for the Constitution. He was even forced to promise to seek a Bill of Rights in order to be elected to the First Congress. His strongly Anti-Federalist district would never have voted for him if he hadn't.

Madison moved quickly once Congress was seated in 1789. Some people had advocated throwing out the Constitution and starting over. He didn't want the hard work he and many others had put into creating the Constitution to go to waste. He believed the compromises the delegates at the Constitutional Convention had made would be very difficult to reach again or to improve upon. He also wanted to propose his amendments first, which focused on the protection of individual rights, before others made proposals that would have made structural changes to the constitution. Indeed, most of the proposals from the states were structural in nature and Madison believed that this would weaken or undermine the Constitution. He also wanted to move quickly on a Bill of Rights in order to secure the ratification of the last two states, North Carolina and Rhode Island, who still had not ratified the Constitution. You can read more about the Bill of Rights' Purpose here.

History of the Bill of Rights -

James Madison's Proposal

On June 8, 1789, Madison presented his proposed amendments to the Congress. In the speech he delivered that day, he said:

"For while we feel all these inducements to go into a revisal of the constitution, we must feel for the constitution itself, and make that revisal a moderate one. I should be unwilling to see a door opened for a re-consideration of the whole structure of the government, for a re-consideration of the principles and the substance of the powers given; because I doubt, if such a door was opened, if we should be very likely to stop at that point which would be safe to the government itself: But I do wish to see a door opened to consider, so far as to incorporate those provisions for the security of rights, against which I believe no serious objection has been made by any class of our constituents."

Madison had studied all of the proposals by the state governments and decided to push for amendments that were widely popular in order to speed up the process and prevent further delay. He also based much of his proposal on George Mason's Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776. Some of Madison's wording is nearly identical to this document. Thomas Jefferson had also relied heavily on it when writing the Declaration of Independence.

James Madison's proposal called for twenty amendments to the Constitution. You can read James Madison's speech to Congress proposing the Bill of Rights here. Only twelve were finally approved by Congress and sent to the States for ratification, and only ten of those were ratified by the States. Some of Madison's amendments were completely rejected by the Congress. Some were drastically altered.

Some of Madison's amendments that did not receive congressional approval included one that preserved the right of religious dissenters to abstain from military service, one that protected freedom of the press from censorship by state governments (first amendment freedoms at this time were considered only to be restrictions of the federal government, not state governments, thus, the state governments could restrict freedom of the press, religion, speech and so forth) and one protecting the right to trial by jury in state criminal cases (again, the right to trial by jury was only applied to the federal government at this time, not state governments).

Madison considered these restrictions on the States' power to be the most necessary of all the amendments, yet they were completely rejected by the Congress. Later on, in the early 1900's the enforcement of these rights was applied to the state governments by the courts, as well as the federal government by the court's interpretation of the 14th amendment. Thus, today, a state cannot restrict these rights any more than the federal government can. You can read the 14th Amendment here.

In studying the history of the Bill of Rights, it should be noted that Madison's proposal did not actually call for a Bill of Rights, but rather for insertions, deletions and revisions of the Constitution to be added right into the text, not a list of rights to be added at the end of the Constitution. It was the whole Congress who decided to add them as a list at the end. Madison also proposed some changes to the Preamble. The rest of the changes were to be inserted into the Constitution wherever they applied, most of them into Article I, Section IX, which dealt with restrictions on the legislative branch, the branch he believed the most prone to usurping the people's rights.

Madison's proposals were not actually taken up until August 13, two months after he had proposed them. The Federalists dominated the Congress and passing a Bill of Rights was not an urgent issue to them. Nonetheless, Madison believed it was necessary to secure confidence in the Constitution and he tried to shepherd his amendments through the House of Representatives. In the end, on August 24, 1789, the House accepted 17 of the amendments, making many changes to Madison's proposals and throwing out his preamble.

History of the Bill of Rights -

Congress passes the Bill of Rights

The Senate received the House's bill and paired the list down to twelve. A joint committee further revised the language of the twelve amendments that were finally chosen to be presented to the states for ratification on September 25, 1789. Read the Twelve Amendments Congress proposed to the States here.

But wait, doesn't the Bill of Rights have Ten Amendments? Yes, that's right. The states rejected two of the proposed amendments. The Constitution requires that 3/4 of the states vote to ratify an amendment to the Constitution and the first two didn't make it.

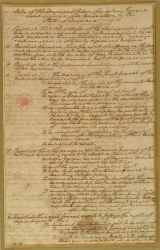

Twelve Proposed Amendments

Twelve Proposed AmendmentsThe Rejected Amendments

Studying the history of the Bill of Rights would be complete without learning about the rejected amendments? What are the two rejected amendments? The first one deals with the number of delegates apportioned to congress based on population. It reads like this:

"Article the first: After the first enumeration required by the first article of the Constitution, there shall be one Representative for every thirty thousand, until the number shall amount to one hundred, after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall be not less than one hundred Representatives, nor less than one Representative for every forty thousand persons, until the number of Representatives shall amount to two hundred; after which the proportion shall be so regulated by Congress, that there shall not be less than two hundred Representatives, nor more than one Representative for every fifty thousand persons."

The second rejected amendment, which was the second on the list, had to do with not allowing Congress to give itself pay raises. It reads like this:

"No Law varying the Compensations for the Services of the Senators and Representatives shall take Effect, until an Election of Representatives shall have intervened."

Remarkably, this amendment did finally become law, but not until 1992, more than 200 years after the First Congress proposed it! It became the 27th Amendment to the Constitution.

Congress approved the Twelve Amendments, or Twelve Articles as they were called, on September 25, 1789. Next, it was time to send them to the States for discussion and rejection or ratification. Congress printed up a copy of the proposed amendments and President George Washington had thirteen handwritten copies transcribed and then sent them off to the governors of each state. The 3/4 requirement stated in the Constitution meant that 11 of the 14 States had to vote in the affirmative on each article for them to become law. There were 14 states by the time it was over, because Vermont was admitted as the 14th state on March 4, 1791.

History of the Bill of Rights -

Ratifying the Bill of Rights

On November 20, 1789, New Jersey became the first state to ratify. New Jersey ratified eleven of the articles, but rejected article two. The ratification dates of each state are listed below.

Notice that Massachusetts, Connecticut and Georgia are not included in this list. That's right. These three states did not vote to ratify the Bill of Rights, until 1939 that is, when they were urged to do so on the 150th anniversary of adopting the Bill of Rights! In spite of these states' unwillingness to pass the amendments, Articles III through XII received the eleven votes that were needed to become law. Article II was rejected by Delaware, so it only had 10 out of 14 votes needed and thus did not pass. Later, after Kentucky became a state, Article I received another vote, giving it 11 of 15 states, but this still did not meet the 3/4 threshold. Article II received only 6 out of 14, later 7 out of 15, with Kentucky added, and thus did not become law. Article I has never become law, but Article II did finally become law in 1992.

James Madison Letter

James Madison LetterEven though the Bill of Rights eventually became law, there was still much opposition from Anti-Federalists. In general they believed that the amendments did not go far enough in safeguarding their rights. Here is an interesting letter from James Madison to George Washington discussing the opposition of Richard Henry Lee to the proposed amendments.

With Virginia's vote for ratification on December 15, 1791, articles III through XII became law as the first Ten Amendments on that day.

Since Congress sent twelve amendments to the states, and the first two were rejected, the third amendment in the original proposal became what we know as the First Amendment today.

History of the Bill of Rights -

Where are they today?

So where are the original copies of the Bill of Rights today? The original copy printed by Congress is housed in the Rotunda of the Charters of Freedom at the National Archives in Washington DC. Two other copies are also held by the National Archives. One is the copy that was sent to the State of Delaware. Which state the other one belonged to is unknown. Eight states still have their copies, some of which are on display. They include Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, South Carolina, Virginia, Rhode Island and North Carolina. One copy is in a public library in New York, but we don't know which state it belonged to. There are two that are completely missing. The two missing copies and the two copies that we have but are unsure to which state they belonged, were the copies from Georgia, Maryland, New York and Pennsylvania.

Learn more about the Bill of Rights with the following articles:

- Main Bill of Rights article.

- For a brief synopsis of the First Ten Amendments.

- Learn about the Purpose of the Bill of Rights here.

- Look at the Bill of Rights in Pictures here.

Amendments:

Preamble to the Bill of Rights

Learn about the 1st Amendment here.

Learn about the 2nd Amendment here.

Learn about the 3rd Amendment here.

Learn about the 4th Amendment here.

Learn about the 5th Amendment here.

Learn about the 6th Amendment here.

Learn about the 7th Amendment here.

Learn about the 8th Amendment here.

Learn about the 9th Amendment here.

Learn about the 10th Amendment here.

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments