8th Amendment

What is the 8th Amendment? This amendment to the US Constitution protects American citizens from being forced to pay extremely high amounts of money for bail if they are accused of a crime, being charged exorbitant fines and from cruel and unusual punishments being inflicted upon them by the government.

The 8th Amendment is part of the Bill of Rights, which is the First Ten Amendments to the United States Constitution. It was the Founding Fathers desire to give the government into the hands of the people and take it away from arbitrary rulers and judges, who might inflict any amount of excessive bail or cruel and unusual punishment they desired. More on the history and purpose of the 8th Amendment below.

Read the 8th Amendment

The 8th Amendment contains three distinct clauses and is the shortest of the Amendments in the Bill of Rights. It reads like this:

"Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted."

Excessive Bail Clause

Bail is an amount of money that must be given to a

court by a person accused of a crime in order for them to be able to

leave the jail before the trial. If the person doesn't show up for his

trial, then he forfeits the money he gave as bail. If the person shows

up on their trial date, the bail money is returned to them.

Sometimes the bail required by a court can be very high and the accused person may not have enough to pay it. In this case, a bail bondsman can loan the money to the accused person for a fee. If the person doesn't show up for the trial, the bondsman loses his money as well, so it is in the bondsman's interest that the accused show up for trial.

When people do not show up for trial, bondsmen often employ bounty hunters to find the person and return them to the jail so they can get their money back. There are several popular television shows such as "Dog, the Bounty Hunter," that show how bounty hunters do their work.

The Excessive Bail Clause of the 8th Amendment prohibits courts from requiring unreasonably large amounts for bail. If the amounts are too large and people cannot pay them, they would have to stay in jail until their trial date. This would prevent an accused person from preparing their defense adequately, since it would be hard to prepare a defense from jail. In addition, allowing an accused person out on bail allows them to continue working to provide for their family and do other normal activities and also reduces expenses for the local jail since they will not have to house and feed the accused.

It is also not fair to leave a person in jail for a long period of time who has merely been accused of a crime because, in the American legal system, people are presumed to be innocent until they are proven guilty. At this stage, they have merely been accused of wrong doing and nothing has yet been proven.

At the same time, courts must set the bail to a sufficiently high amount so that the accused person will have an incentive to show up for their trial because if they do not show up, they will lose their money. If the bail is too small, the person may flee or just not show up.

Courts must also protect the community. So in some cases, they will not allow someone to pay bail and get out of jail. This happens if the alleged crime is particularly heinous or if releasing the person would cause some unusually dangerous threat to the community.

Excessive Fines Clause

The Excessive Fines Clause prevents judges from levying excessive fines, but what amount is excessive? In actuality, fines are rarely overturned by higher courts unless the judge abused his discretion when imposing the fine. Using this standard, a higher court may reverse a lower court's arbitrary, exorbitant fines if they are "so grossly excessive as to amount to a deprivation of property without due process of law," Water-Pierce Oil Co. vs Texas . Fines are rarely reversed due to any of these 8th Amendment conditions.

Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause

Appeals courts usually defer to the lower courts in cases regarding challenges based on violations of the Excessive Bail Clause or Excessive Fines Clause. Courts give much more scrutiny, however, to cases alleging violations of the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause.

The 8th Amendment requires that punishments for crimes be in proportion to the crime committed. Punishments that are far greater than the crime should demand can be overturned by a higher court. For example, the courts have ruled that the death penalty is out of proportion to any other crime than one where a murder is committed, except for crimes against the government such as treason and spying.

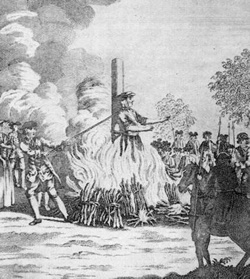

The courts have also ruled that if a sentence is inhuman, outrageous, or shocking to the social conscience, it is a cruel and unusual punishment under the 8th Amendment. Such things as burning at the stake, castration, crucifixion, breaking on the wheel, cutting off body parts and so on, fall into this category.

In particular, cases involving the death penalty have received a lot of scrutiny in regards to the 8th Amendment. There are some people who believe all death penalties constitute a cruel and unusual punishment. Others disagree, believing that death is an appropriate punishment in some cases.

The courts have generally decided that death is an appropriate punishment for murder, but not for other crimes. Even so, the death penalty is "cruel and unusual" if there are mitigating factors that would prohibit death as a punishment, such as if the convicted person was mentally incompetent at the time the crime was committed.

History of the 8th Amendment

The 8th Amendment has its origin in the British Magna Carta of 1215. In it, the idea that punishments ought to fit the crime was codified in the following words - "A free man shall not be [fined] for a small offense unless according to the measure of the offense, and for a great offense he shall be [fined] according to the greatness of the offense." Magna Carta was the first English document that placed restrictions on the sovereign from violating certain agreed upon rights of the people.

In 1689, this principle was put into the English Bill of Rights by Parliament, declaring "as their ancestors in like cases have usually done... that excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted." The inclusion of this statement in the English Bill of Rights was largely due to the famous case of Titus Oates.

Oates was tried and convicted of lying in court. Several people had been executed as a result of his untrue statements in court. The punishment he received included imprisonment and an annual ordeal which included being confined in a pillory for two days and one day of being whipped while tied to a moving cart.

The pillory is a device where the person's head and hands are secured in a wooden frame, which is usually placed in a public place where passersby can taunt them and throw garbage at them. The main purpose for such a device is public humiliation.

Both of these punishments, the pillory and whipping, were common punishments at that time. What was so offensive to the English people was the fact that the punishment was to be given over and over again every year. Though the punishments were ordinary, they became extraordinary and excessive due to their repetition year after year. Members of Parliament referred to the Titus Oates case specifically when explaining why they wrote these provisions about excessive punishment into the English Bill of Rights of 1689.

The famous British jurist and judge Sir William Blackstone is one of the most often quoted persons by the Founding Fathers. He was the preeminent lawyer and legal analyst of his time and his writings were studied and adhered to by generations of English lawyers. In Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England, he says that the "cruel and unusual punishments clause" was added to restrict the discretion of judges and make them follow established and acceptable precedent:

"However unlimited the power of the court may seem, it is far from being wholly arbitrary; but its discretion is regulated by law. For the bill of rights has particularly declared, that excessive fines ought not to be imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted: (which had a retrospect to some unprecedented proceedings in the court of king's bench, in the reign of king James the second)..."

Read Blackstone's complete comments about the proportionality of punishment to a crime here.

In June, 1776, the Virginia Declaration of Rights was approved and passed unanimously by the Fifth Virginia Convention at Williamsburg, Virginia. This Declaration of Rights was written by George Mason and included the phrase, "That excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed; nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted," which was drawn nearly word for word from the English Bill of Rights of 1689.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights was the first statement of belief regarding the rights of man by any American government. It predated the Virginia Constitution by several weeks and the Declaration of Independence by a few months. Thomas Jefferson is thought to have drawn many ideas for the Declaration of Independence directly from the Virginia Declaration of Rights. See our page about how Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence here.

It is clear that the Founding Fathers were intent to prevent any government from laying abusive fines or punishments on anyone. When it came time to debate whether or not to adopt the United States Constitution, the issue arose once again. Again the state of Virginia proposed that a Bill of Rights be added to the Constitution and that a statement prohibiting excessive punishments should be included. Both Virginia and Massachusetts insisted that such a Bill of Rights be added.

James Madison, the author of the amendments, included the 8th Amendment in his original list of twelve amendments. The first Congress and the states adopted ten of them. These first ten amendments are known as the Bill of Rights. They included the 8th Amendment, which read almost exactly as Mason wrote it into the Virginia Declaration of Rights:

"Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted."

The 8th Amendment in American life

Over the years, the Supreme Court has basically determined that the 8th Amendment

forbids some punishments completely, while forbidding other punishments

that are excessive in comparison to the crime, or in comparison to the

mental competence of the accused.

Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause

In Wilkerson v. Utah, 1878, the Supreme Court commented that drawing and quartering, burning alive, disembowelling and public dissecting would constitute cruel and unusual punishment under the 8th Amendment no matter what the crime, but they did not make their first ruling overturning a case regarding an allegation of cruel and unusual punishment, until 1910.

In this case, Weems v. United States, the Supreme Court overturned a practice called cadena temporal, which ordered "hard and painful labor," shackling for the length of incarceration and severe civil restrictions. This case is often viewed as establishing a "principle of proportionality," meaning the punishment must be in proportion to the crime.

In later years, however, some justices on the Court have begun turning away from this principle, in favor of the notion that the 8th Amendment does not contain any promise regarding proportionality, but instead is meant only to insure that certain punishments are forbidden regardless of the circumstances.

The Supreme Court has ruled that taking away an American citizen's citizenship as punishment for a crime is cruel and unusual. The Court has also ruled that punishments cannot be imposed because of a person's "status," such as if they have a certain illness or addiction. In other words, punishments can only be handed out for actions committed.

Regarding the punishment of minors, in 2005, the Supreme Court ruled that executing someone who was under the age of 18 when the crime was committed violates the 8th Amendment. While, in 2010, the Court ruled that a sentence of life without the chance for parole, for any crime besides murder, is cruel and unusual punishment if the accused is under the age of 18.

Some punishments have been challenged as violations of the 8th Amendment, but the Courts have determined that they are not cruel and unusual. These include lethal injection, hanging, the firing squad and the electric chair. How is it determined whether or not a punishment is "cruel and unusual?" Generally speaking, if a majority of Americans find a punishment to be cruel and unusual, the Court will ban it. If a majority find a punishment to be acceptable given the crime, the Court will allow it.

The majority of Americans still find lethal injection, hanging, the firing squad and the electric chair to be justifiable punishments. In reality, lethal injection is the standard form of capital punishment that is still practiced, although one person was executed in Utah by firing squad in 2010 and one by electrocution in Virginia in 2010 as well. No one has been executed by hanging in the United States since 1996.

The Supreme Court has also determined that prison conditions for those who have been convicted can be cruel and unusual, thus violating the 8th Amendment.

Such things as unnecessarily harsh treatment, lack of basic life

necessities, racial segregation for reasons other than prison security

and restrictions on one's ability to petition the government for redress

of grievances would fall into this category.

Excessive Fines and Excessive Bail in daily life

Court cases based on the Excessive Fines Clause and the Excessive Bail Clause have been rare in the 200 plus years since the 8th Amendment was written. In fact, the first time the Supreme Court overturned a ruling based on a violation of the Excessive Fines Clause did not happen until 1998.

In that case, a Mr. Bajakajian was fined $357,144 for taking more than $10,000 in cash out of the United States without reporting it. You can legally take more than $10,000 in US currency out of the country, but you must report it to the authorities. The Supreme Court ruled that the fine was grossly disproportional to the crime.

Supreme Court Building

The Excessive Bail Clause has also not been used much since its inclusion in the 8th Amendment either. One important question the Supreme Court has had to address regarding it's meaning has been whether or not the clause requires that bail be offered to all defendants, or whether there are some cases for which the judge can detain the accused and not allow them bail.

The excessive bail idea worked it's way into British law over many centuries in order to prevent judges from inappropriately incarcerating people for their political affiliations or for other unjust reasons. The Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 established set procedures for releasing people from jail and created penalties for judges who violated the Act. Habeas Corpus is a judicial order requiring the release of people unlawfully detained.

Eventually, corrupt judges found a way around the Habeas Corpus Act by ordering excessive fines that people were unable to pay, thus ensuring their confinement. Eventually, the English Bill of Rights of 1689 was adopted, which stated that "excessive bail ought not to be required."

This Bill, however, did not express which crimes were bailable and which ones were not, as had been the case in previous documents such as the Petition of Right of 1628 and the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679. Consequently, since the British precedent did not specify which crimes were bailable, the American courts have determined that there are crimes for which bail may be denied if the charges are highly serious. For example, if a court determines that releasing an individual would provide a threat to the community, he may be detained without being given the opportunity to pay bail. This is called "preventive detention."

The only limitation expressed in the Excessive Bail Clause, according to the Supreme Court, is that "the government's proposed conditions of release or detention not be 'excessive' in light of the perceived evil." What is excessive? Bail is "excessive" according to the Court, if it is set at a higher amount than is necessary to ensure the government's interest.

If the only relevant interest is to guarantee that the accused will show up for trial, then "bail must be set by a court at a sum designed to ensure that goal, and no more." There may, however, be other government interests, such as the person providing a threat to the community, which can be taken into account as well. In that case, bail can be denied if there is just reason to do so.

8th Amendment - the Death Penalty

The number one most litigated issue having to do with the 8th Amendment has been regarding the death penalty. The issue of the death penalty, as you may know, is one that elicits very strong emotions from its supporters and from its detractors. There are those who believe that capital punishment is just in the case of murder or other serious crimes such as rape. There are other people who believe the death penalty should be banned whatsoever, believing that it is inhumane, making the government no better than the murderer. Those who support the death penalty often believe it provides a strong deterrent to others who may consider committing serious crimes.

Even among the Founding Fathers, there were differing opinions on this issue. Below, you can read short writings from several founders: Thomas Jefferson, who supported the death penalty, Benjamin Rush, who opposed it in all circumstances and James Wilson, who, while not mentioning the death penalty specifically, advocated less stringent punishments, believing that judges and juries would be less likely to impose them because of the squeamishness of human nature and that this would encourage more crime.

- Thomas Jefferson letter to Edmund Pendleton, August 26, 1776

- James Wilson to a Grand Jury, 1791

- Benjamin Rush on the Death Penalty, 1792

Whether or not capital punishment is legal is up to each state for state crimes. As of March, 2011, fourteen states have banned the procedure, including Alaska, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia and Wisconsin. The other 37 states allow the death penalty, in addition to the federal government for certain federal crimes.

The death penalty was allowed by the Supreme Court up until 1972. Before then, the death penalty was considered an acceptable form of punishment for certain serious crimes, especially murder, since the time of the original thirteen colonies, all of which allowed the death penalty.

By the mid 20th century, however, the Court's opinion about capital punishment began to shift slightly and in a pivotal case called Furman v. Georgia, the Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty could not be applied in an arbitrary or capricious manner. In other words, there did not seem to be any set of rules regarding which crimes would or would not receive the death penalty. Indeed, the majority of justices in this case thought the death penalty was given merely because of the accused's race.

This ruling caused all states that allowed the death penalty to stop executions and rewrite their death penalty laws. This angered many who were against the death penalty altogether, who had hoped that the Furman case would end the procedure permanently.

By 1976, the Court reviewed another series of cases regarding the states' new laws about the death penalty. In Gregg v. Georgia, the Court upheld a procedure in which the trial and sentencing are "bifurcated" into two separate events - the trial where the guilt or innocence is determined and the sentencing. At the trial, the jury determines the defendant's guilt. At the second hearing, if the person was found guilty, the jury determines whether certain legal factors exist, such as whether or not a gun was used in the crime. These legal factors that may affect the sentencing are written into law. In addition, the jury may consider any other mitigating factors, such as whether the person had reduced mental capacity.

The bifurcated trial set the Court's concerns about arbitrary application of the death penalty at ease and those states which wished to resume the practice did so in line with the new guidelines.

In 1977, Coker v. Georgia forbade the death penalty in a case of rape, on the grounds that taking someone's life was cruel and unusual if they had not taken someone else's life first. This effectively barred the death penalty in all cases except for murder.

The death penalty is still on the books for some other crimes in some states such as for aggravated rape in Louisiana, Florida and Oklahoma; drug trafficking resulting in a person's death in Connecticut and Florida; aggravated kidnapping in Georgia, Idaho, Kentucky and South Carolina; aircraft hijacking in Alabama; extortionate kidnapping in Oklahoma; and trainwrecking or perjury leading to a person's death in California. However, in practice, no one has been executed for a crime other than murder or conspiracy to commit murder since 1964.

In 2008, in Kennedy v. Louisiana, the Supreme Court reiterated this rule by ruling against a Louisiana law that instituted the death penalty for child rapists. The Court ruled that:

"There is a distinction between intentional first-degree murder on the one hand and non-homicide crimes against individual persons."

The Court also stated that the death penalty for any crime against an individual, "where the victim's life was not taken," was unconstitutional.

There is a federal exception to the rule that the death penalty can only be applied, however, in cases of murder. The federal government is allowed to use the death penalty in cases of treason, espionage and crimes against the state.

The Supreme Court placed two other severe restrictions on the use of the death penalty on 8th Amendment grounds. In 2002, the Court ruled that executing a mentally retarded person was cruel and unusual. In general, a person is considered to be mentally retarded if they have an IQ less than 70.

Second, in 2005 the Court ruled that executions of people who were under 18 at the time of the crime are cruel and unusual and therefore violations of the 8th Amendment. Their reasoning included the fact that teenagers are not as responsible for their actions as adults due to their youth and inexperience in life.

For further information, read our 8th Amendment Court Cases page, which gives some detail about important cases regarding the 8th Amendment.

If you would like to read about the meanings of each amendment, go to the First Ten Amendments page here.

Amendments:

Preamble to the Bill of Rights

Learn about the 1st Amendment here.

Learn about the 2nd Amendment here.

Learn about the 3rd Amendment here.

Learn about the 4th Amendment here.

Learn about the 5th Amendment here.

Learn about the 6th Amendment here.

Learn about the 7th Amendment here.

Learn about the 8th Amendment here.

Learn about the 9th Amendment here.

Learn about the 10th Amendment here.

- Main Bill of Rights page.

- For a brief synopsis of the First Ten Amendments go here.

- Learn about the Purpose of the Bill of Rights here.

- Read about the History of the Bill of Rights here.

- Look at the Bill of Rights in Pictures here.

Revolutionary War and Beyond Home

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments