Star Spangled Banner Flag

The Star Spangled Banner Flag is the name for the American flag with 15 stars and stripes. It got the name because this is the flag that was flying at Fort McHenry during the War of 1812 that Francis Scott Key saw when he wrote the poem "Defense of Fort McHenry." He put it to the music of a familiar tune and it later became known as the "Star Spangled Banner," America's National Anthem. The original Star Spangled Banner Flag that flew over Fort McHenry still exists and can be viewed at the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC.

History of the Star Spangled Banner Flag

Star Spangled Banner Flag

Star Spangled Banner FlagThe first official description for the United States Flag was laid out by Congress in the Flag Resolution of 1777. It stated:

Resolved, That the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new Constellation.

The Flag Resolution set the precedent of 13 red and white stripes, along with the stars representing the states on the blue field. Before this, through a period of many years, the colonists in America had gone through many versions of flags, starting with the British Red Ensign, which was the official flag of Great Britain. This flag led to the Grand Union Flag, which was probably the first flag carried by the Continental Army.

Cowpens Flag

Cowpens FlagNotice that the Flag Resolution does not state the pattern in which the stars should be arranged. This led to flags with the stars in many different arrangements in the early days of the republic, such as the Cowpens Flag, the Guilford Courthouse Flag, the Betsy Ross Flag, the 13 Star Flag, the Bennington Flag and the Serapis Flag.

In 1794, Congress passed the Flag Act of 1794, adding two stars and two stripes to the flag to represent the 2 recently added states, Vermont and Kentucky. The Flag Act of 1794 reads:

An Act making an alteration in the Flag of the United States.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America

in Congress Assembled, That from and after the first day of May, Anno Domini, one

thousand seven hundred and ninety-five, the flag of the United States, be fifteen

stripes alternate red and white. That the Union be fifteen stars, white in a blue

field.

Notice the Act still did not define the pattern for the stars. Congress was apparently happy to allow flag manufacturers and the American people to put the flags in whatever pattern they chose. Most flags by this point and afterwards used the pattern with staggered rows, but there were other arrangements used as well.

The Flag Act of 1794 made the only official version of the US Flag with more than 13 stripes, making the Star Spangled Banner Flag the only American Flag with 15 stripes. This flag lasted officially until the Flag Act of 1818, when Congress set the rule that the stripes would always remain at 13 and the stars would reflect the number of states with a new star to be added on the July 4th after a new state was added to the Union. The Flag Act of 1818 reads:

An Act to establish the flag of the United States.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America,

in Congress Assembled, That from and after the fourth day of July next, the flag of the

United States be thirteen horizontal stripes, alternate red and white: that the union

be twenty stars, white in a blue field.

And be it further enacted, That on the admission of every new state into

the Union, one star be added to the union of the flag; and that such addition

shall take effect of the fourth day of July then next succeeding such admission.

The Star Spangled Banner in the War of 1812

Fort McHenry

Fort McHenryIt was 1814, the final year of the War of 1812, when Great Britain sent 50 ships up the Chesapeake Bay. On August 24, British soldiers invaded Washington DC, burning the Capitol, the White House and other buildings and causing President James Madison and his wife Dolley to flee the city, narrowly avoiding capture.

Before the Chesapeake invasion ever occurred, the city of Baltimore was anticipating an attack as well. Baltimore was an important colonial shipping center and was third largest city in America at the time with 46,000 residents. Fort McHenry sat on the harbor guarding the city and its commander was Major George Armistead. Major Armistead wanted to have a very large flag made for the fort, "a flag so large that the British would have no difficulty seeing it from a distance."

Mary Young Pickersgill

Mary Young PickersgillMajor Armistead commissioned Mary Young Pickersgill in July, 1813 two make two flags for the fort. Pickersgill was a local Baltimore flagmaker. Her mother, Rebecca Young, was a maker of American Flags during the American Revolution. According to the Pickersgill family tradition, Rebecca had sewn the first American Flag at the request of George Washington, but historians doubt this story. You can learn more about the "first" American flag at our 13 Star Flag page.

Of the two flags Pickersgill was to make, the larger one, which was the largest military flag ever flown at the time, was to be 30 feet by 42 feet and was known as the Great Garrison Flag. This is the flag that has survived and is held at the Smithsonian Institution. This flag is so large that it is about 1/4 the size of a modern basketball court and is larger than the standard size garrison flags used by the United States Army today, which is 20x38 feet.

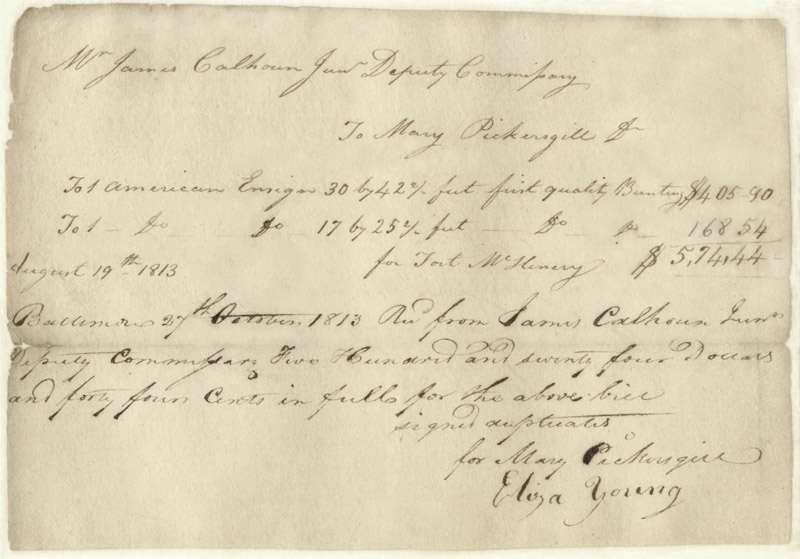

Star Spangled Banner Flag Receipt

Star Spangled Banner Flag ReceiptThe second flag was the Storm Flag, a smaller version to measure 17x25, that would be flown in inclement weather. This smaller flag was less likely to be damaged or blown off in a storm.

The total bill to Mary Pickersgill was $574.44. A receipt for the flags dated August 19, 1813 and signed by James Calhoun, Junior Deputy Commissary, has survived, which you can see at the left.

Making of the Star Spangled Banner

Mary Pickersgill obtained permission from a local business, Claggett's Brewery, to use the floor of their malt house to spread out the Star Spangled Banner Flag because it was so big. She was assisted by her 13 year old daughter Caroline Young, her nieces Eliza and Margaret Young, who were 13 and 15 and an African American servant, Grace Wisher, who was also 13.

It took them about 7 weeks to make the two flags, which were pieced together using many smaller 12 to 18 inch strips of cotton and English wool bunting. The stars are about two feet in width and the points go in multiple directions, as opposed to all of them pointing to the top as they do on today's flag. Each stripe is also about two feet wide.

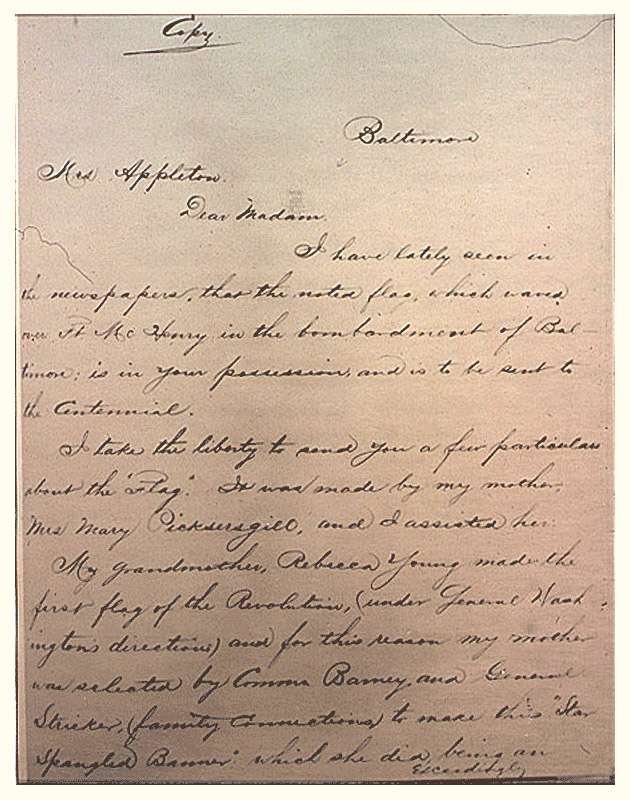

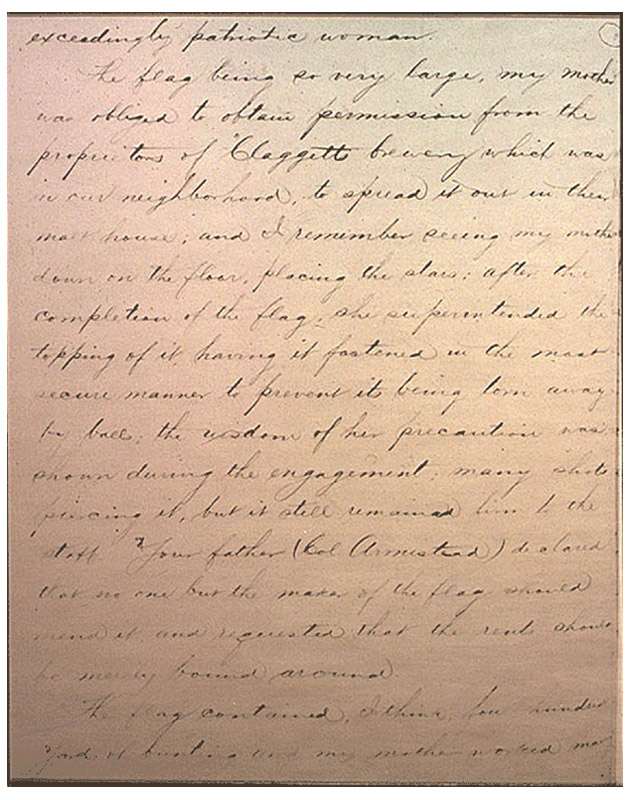

A very interesting letter has survived from Caroline (Young) Purdy, Mary Pickersgill's daughter, that she wrote to Georgiana (Armistead) Appleton, the daughter of Major Armistead, in 1876. The Star Spangled Banner Flag had been in the possession of the Armistead family for many years at this time. Caroline was very old and had fallen on hard times financially. 1876 was the United States 100th anniversary and the flag was going to be displayed for the celebrations. The purpose of her letter was to ask permission from Georgiana to use the fervor and national patriotic feeling toward the Star Spangled Banner Flag to her own advantage by printing up her family's connection to the flag and attaching it to the flag in hopes that some people would be inspired by it to help her financially.

Flag historians are interested in the letter because Caroline relates some interesting facts about the creation of the flag, such as it being made at the Claggett's malt house and how her mother stayed up until midnight working on the flag many nights. You can view the Caroline Purdy letter to Georgiana Appleton by clicking the links in the picture above and to the right and you can read the complete text of the Caroline Purdy letter to Georgiana Appleton here.

The home of Mary Pickersgill has also survived and today houses a museum called the Star Spangled Banner House. The museum features exhibits from the time period. It has actors portraying Pickersgill and other members of the household, as well as activities for kids. For more about visiting times and directions, check out the Star Spangled Banner House website.

Star Spangled Banner House Baltimore, Maryland

Star Spangled Banner House Baltimore, MarylandStar Spangled Banner at the Battle of Baltimore

The British began their bombardment of Fort McHenry on September 13 and rained down rockets and mortar shells on the fort for 25 hours. The fort sustained damage, but was not destroyed due to recent fortifications and due to malfunction in some of the British cannonballs. Because they were not able to get past the fort into Baltimore Harbor, British Admiral, Sir Alexander Cochrane called off the attack and sailed for New Orleans, where he would fight in the last battle of the War of 1812, the Battle of New Orleans, with future president, Andrew Jackson.

On the night of the bombardment of Fort McHenry, a Washington DC lawyer and amateur poet named Francis Scott Key was sitting in a British ship, the HMS Tonnant, within sight of the battle. Key was on board as a guest of Admiral Cochrane. He had come along with American Prisoner Exchange Agent Colonel John Stuart Skinner, to help in the negotiations for the release of several American prisoners. While on board, Key and Skinner had learned of the British plans for attacking Baltimore, so they were not allowed to leave until the battle was over so they would not reveal the plans to the Americans. This left Key on board to watch the bombardment of Fort McHenry through the night.

Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott KeyThe smaller "storm flag" was flown over Fort McHenry during the night because of a heavy rain storm, but in the morning the 30x42 Great Garrison Flag was hoisted up over the fort as a sign that the Americans were still in control and the fort had not been destroyed. With the "dawn's early light," Key was thrilled to see the flag flying over the fort. He began to write down, on the back of a letter, the words of a 4 stanza poem to describe the victory.

On the 16th, Key and the others were released and he returned to Baltimore where he rented a room at the Indian Queen Hotel. He spent the evening revising the poem and the following day shared it with his wife's brother-in-law, Judge Joseph Nicholson, who had fought at Fort McHenry. Judge Nicholson liked the poem and encouraged Key to have it published. It was printed up on the 17th by a local printer and distributed to all the men who had been at Fort McHenry during the bombardment, under the title Defence of Fort McHenry, with instructions that it be sung to the tune "To Anachreon of Heaven." This song was written in 1775 for the Anachreontic Society in London, a society of amateur musicians. Anachreon was a Greek poet known for his songs about love and wine.

On September 20th, Defence of Fort McHenry was published in the Baltimore Patriot for the public for the first time. The first documented performance of the song occurred at the Holliday Street Theatre in Baltimore on October 19th and soon a local music store began to publish the song under the name "The Star Spangled Banner," taking the title from the last line of each stanza. This is where the name "Star Spangled Banner" came from. You can read the complete Star Spangled Banner lyrics here.

Significance of "The Star Spangled Banner"

Before the War of 1812, even during the Revolutionary War, the American Flag was not particularly considered a national patriotic symbol. It didn't fly from homes or inspire patriotic zeal in people's hearts. It was merely a symbol used to identify ships and military regiments. Instead, early Americans used other symbols, such as the American eagle, "Lady Liberty" portrayed as a goddess, or figures such as George Washington, to represent this type of patriotism.

The writing of the Star Spangled Banner song became a key event in turning the flag into the symbol it is today, fused with pride, patriotism and American values. The Battle of Baltimore was considered to be a great American victory of the War of 1812 by the American people. Key meshed the symbolism of the flag with the zeal and fervor of victory for a new generation of Americans who had not been alive at the time of the American Revolution.

Through the rest of the 1800s, the Star Spangled Banner song became more and more well known and beloved. During the Civil War, it gained special prominence because of the American spirit and ideals which it represents. It was adopted by the US military in the 1890s for ceremonial purposes, such as the raising and lowering of the US flag. In 1917, the US Army and US Navy adopted the song as the "national anthem" to be played for military ceremonies. After many years of campaigning, patriotic Americans were able to persuade Congress to adopt "The Star Spangled Banner" as the official national anthem of the United States. It was signed into law by President Herbert Hoover on March 3, 1931.

The Star Spangled Banner Flag after the War of 1812

Georgiana Appleton

Georgiana AppletonSome time after the Battle of Baltimore, the Star Spangled Banner Flag ended up in the possession of Major George Armistead, the major who had commissioned its making from Mary Pickersgill. The flag remained in the possession of the Armistead family and fell into the possession of George's wife Louisa upon his death in 1818. When Louisa died in 1861, the flag passed to the Armisteads' daughter, Georgiana Armistead Appleton. Georgiana realized the significance and patriotic sentiment attached to the flag and allowed it to be displayed at public events in Baltimore, including the 1824 tour of the United States by the Marquis de Lafayette, the last surviving French general from the Revolutionary War and close friend of George Washington. It was also displayed at the 1876 centennial celebration of American Independence.

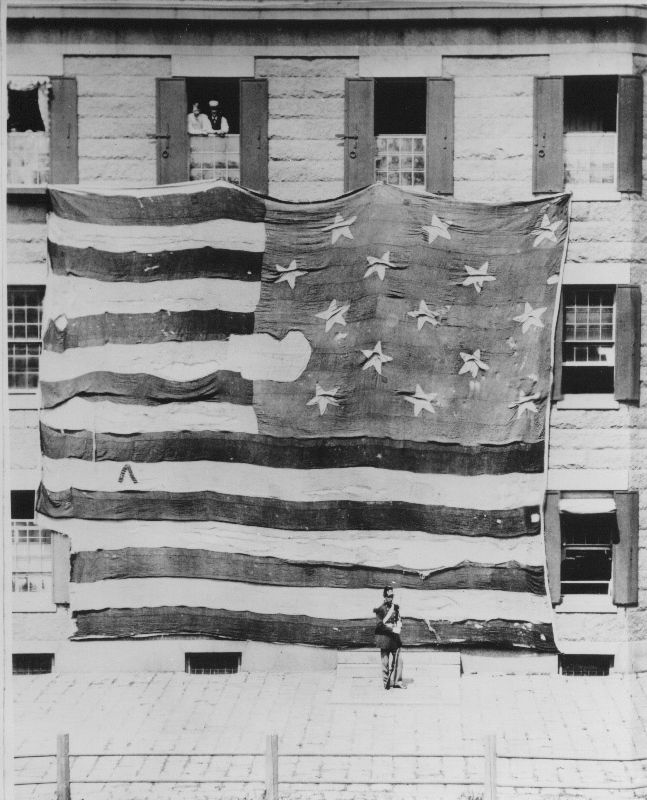

Over the years, the Armistead family had the unfortunate habit of cutting off small pieces of the flag to give to people as souvenirs. They were selective in whom they chose for the fragments, however, only giving them to veterans, government officials or other noteworthy people. Georgiana later wrote, "Indeed had we have given all we had been importuned for (asked for), little would be left to show." Approximately 200 square yards of the original flag were given away in this manner, including one of the 15 stars. The remaining portion of the flag now measures 30x34 feet, down from the original 30x42 feet. Some of the flag pieces remain today in private and public collections.

First Photo of the Star Spangled Banner Flag

First Photo of the Star Spangled Banner FlagThe first known picture of the Star Spangled Banner Flag was taken in 1873 at the Boston Navy Yard. The flag was spread out and hung from third story windows for the picture that went into a book about the history of America's flags written by Admiral George Preble called "History of the Flag of the United States of America." Before the publishing of this book, the existence of the original Star Spangled Banner Flag was largely unknown by Americans outside the city of Baltimore. With the publishing of the book, the flag became more widely known and came to be considered a national treasure.

Eben Appleton

Eben AppletonWhen Georgiana Armistead Appleton passed away in 1878, the Star Spangled Banner Flag passed to Georgiana's son, Eben Appleton. Eben continued to allow the flag to be displayed in public for patriotic occasions, but he also began to look for a permanent location to store and care for the flag. Eben was a New York stockbroker and he kept the flag in New York. In 1880, he allowed the flag to be displayed at Baltimore's sesquicentennial celebration, but he had it put in a safe-deposit vault in New York after that to try to keep it safe. In 1907, Eben gave the flag to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC for safekeeping and in 1912 he donated it as a permanent gift to the nation.

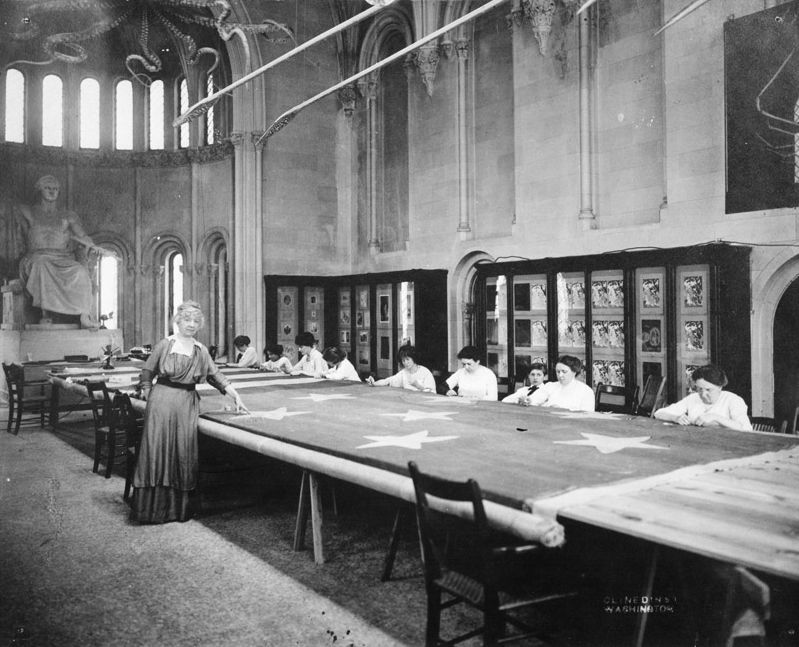

Star Spangled Banner Flag Preservation by Amelia Fowler in 1914

Star Spangled Banner Flag Preservation by Amelia Fowler in 1914When the Star Spangled Banner Flag was donated to the Smithsonian in 1912, it was already tattered and in very poor condition. The Institution began a restoration effort in 1914 by hiring Amelia Fowler, a well-known flag restorer and seamstress. She hired ten seamstresses who worked on the flag for eight weeks. First they removed a canvas backing that had been attached to the flag for the 1873 Boston Navy Yard photo. Then they attached a new linen backing with 1.7 million stitches to form a honeycomb mesh across the back of the flag. This mesh of stitches was intended to secure the fabric of the flag and prevent it from falling apart.

After its restoration, the Star Spangled Banner Flag was stored in a glass case in the Smithsonian's Arts and Industries Building, where it remained for the next 50 years, with the exception of two years during World War II when it was moved to a warehouse in Virginia to protect it if the capital was bombed.

Star Spangled Banner Flag National Museum of American History Flag Hall 1964-1998

Star Spangled Banner Flag National Museum of American History Flag Hall 1964-1998In 1964, the Star Spangled Banner Flag was moved to the newer National Museum of History and Technology building, which is now called the National Museum of American History, where it was hung in the central hall of the second floor, known as Flag Hall. Due to further deterioration because of light and exposure, the flag underwent a two year preservation effort starting in 1981. The flag was cleaned and new lighting and ventilation systems were installed, along with a screen mounted in front. The screen covered up the flag to protect it from light, but was lowered once an hour for visitors to see.

In 1996, the Smithsonian began to develop a long term project to preserve the Star Spangled Banner Flag using modern preservation techniques. The flag preservation formally began in 1998 with its inclusion in the "Save America's Treasures" program, a program chaired by First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton to save America's treasures for the new millenium. The flag was removed at this time and put in a climate controlled laboratory for preservation. It took two years for conservators to remove the 1.7 million stitches from the 1914 Fowler restoration. The flag was cleaned using cosmetic sponges and an acetone/water cleaning solution. Finally, a lightweight fabric called Stabiltex was attached to one side that will hold the fabric together and prevent it from falling apart.

Current Star Spangled Banner Flag Exhibit Smithsonian Institution

Current Star Spangled Banner Flag Exhibit Smithsonian InstitutionWhen the 1998 preservation efforts began, the Star Spangled Banner Flag was removed from Flag Hall in the National Museum of American History where it had been located for 34 years. The entire flag display area was dismantled, including the Foucault Pendulum pit in the center of the hall to make room to build the flag's new permanent exhibit.

The Smithsonian Institution developed a long term plan for preserving the Star Spangled Banner Flag and teaching its significance to the next generation of Americans. On November 21, 2008, it opened the Star Spangled Banner Gallery, the flag's new permanent home, which was built in place of the previous Flag Hall at the National Museum of American History. The flag sets at an angle inside a climate and light controlled chamber with the first words of Francis Scott Key's Star Spangled Banner song on the wall above and behind it. The corridor leading to the gallery sets up the scene for the Battle of Baltimore and the corridors leading away from the flag explain its history in more depth. You can learn more about the National Museum of American History's exhibits and visiting hours here.

You can read the text of the Eben Appleton letter to Charles Walcott, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in 1912, in which Appleton expresses in confidence in the Institution to care for his family treasure, the Star Spangled Banner Flag.

Star Spangled Banner Songs and Videos

And now for a little Star Spangled fun! First are two recordings of the Star Spangled Banner song. First is a recorded version of "To Anachreon in Heaven," the song Francis Scott Key used for the tune of the Star Spangled Banner. Click on the link to listen to To Anachreon in Heaven. You can read the complete lyrics of To Anachreon in Heaven here.

The second song is a sample of how the Star Spangled Banner would have sounded to listeners in the 19th century. It is recorded using 19th century instruments from the Smithsonian's collection and an arrangement by composer GWE Friederich, as it would have been heard in 1854. Click on the link to listen to the 1854 version of The Star Spangled Banner.

Thanks to the National Museum of American History for these songs.

Next are three of the most viewed recordings of the Star Spangled Banner lyrics from YouTube. These are some very inspiring performances. If they don't stir your patriotic feelings and bring tears to your eyes, well... you are dead. Be sure to let the videos download completely before watching so they won't be jerky.

An oldie but a goodie: The first recording is from the 39th SuperBowl in 2005 and is performed by the joint choirs of the United States Naval Academy, United States Air Force Academy, United States Military Academy at West Point, United States Coast Guard Academy and the United States Army Herald Trumpets.

This version, by Madison Rising, has become popular in the last few years.

Learn more about other historical American Revolution Flags here.

Article published October 10/24/11

Revolutionary War and Beyond Home

Like This Page?

© 2008 - 2022 Revolutionary-War-and-Beyond.com Dan & Jax Bubis

Facebook Comments